In France, a hundred years after the end of the First World War, there are dozens of haunted villages. All houses were destroyed, all residents fled, explosives are still everywhere.

Pierre Guérin (70) trudges through the trees with his back bent and gloomy. He does not run here reluctantly, but still. “We never actually talk about the war at home.”

The red-brown autumn leaves crackle under his sneakers. “Look there,” he says. There is a huge pit between the trees, a few meters deep. “A crater. A bomb has come down here. You see those holes everywhere.”

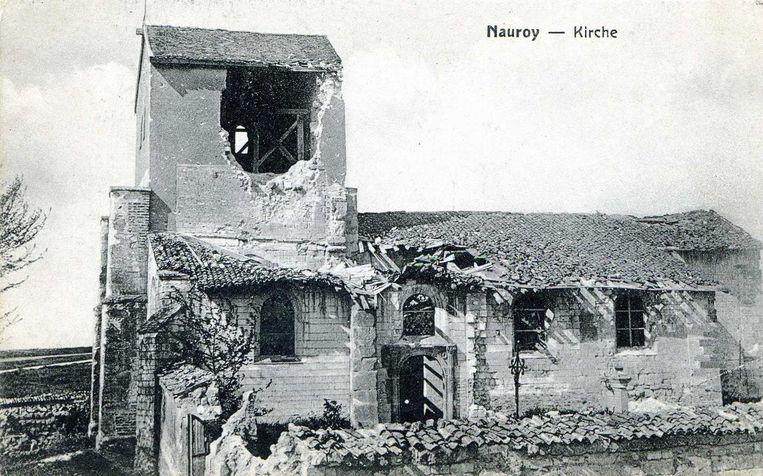

Nauroy

He stops at a stone peg. “Yes, this must be.” The family name Guérin is on it. “Here was our farm more than a hundred years ago. In this village, Nauroy. My grandfather Isidore lived there, he had seven children, and his three brothers also lived here.” But now there is nothing left behind the pole. Only weeds grow. “Everything has been shot here. Everyone had to flee, my family too. The village was destroyed. The only thing you can still find here are grenades.”

The so-called zone rouge is located in northern France. It is an immense area of hundreds of kilometres where during the First World War fierce and prolonged fighting. But where it is still dangerous.

To this day, explosives are found. The soil can be contaminated by the use of poison gas at the time. Often there is barbed wire to keep out visitors. In Nauroy there is only a sign: Military terrain. Forbidden access.

France charged a special explosives disposal service with the sweeping of the rouge zone. But it seems to be mopping with the crane open. “Millions and millions of artillery shells have been fired,” noted British historian Christina Holstein a few years ago. “Probably another three hundred years will be needed to get the complete battlefield ‘clean’. If that were to happen…”

1914 and 1918

There are 24 so-called ghost villages in the rouge zone, such as Nauroy. They were completely destroyed between 1914 and 1918. Wiped away and never rebuilt. The villages are bare, empty and silent, but they still exist officially. France wanted to keep them as a gloomy tribute to the past.

In Nauroy there is a sign at the entrance: destroyed village, behind it empties the emptiness. Other extinct ghost towns have been given another official title: “mort pour la France”, died for the homeland.

Nauroy, next to Reims, was a small farming village before the war, with arable farming and cattle breeding. There were 37 houses and farms and about 120 adults and children lived there. On old photographs, the shepherd of the village can be seen with his flock. The inhabitants were poor, but life could be pleasant, according to archival documents.

“In June of 1914 there was a village party, it was amazing. The sun was shining, garlands were hanging on the walls. And the white wine was pouring in the café,” Henri Guérin told a local newspaper in 1963. Henri Guérin was a brother of Isidore, the grandfather of Pierre Guérin, with whom we walk through Nauroy.

Imprisoned

Three months after that party in the summer of 1914, hell broke loose. The Germans marched into the village. Houses were destroyed, farms plundered. The residents fled: on farm carts, a few with a bicycle and rest were walking. “Some of the people were overtaken by the enemy and had to return to Nauroy. Six men between the ages of 18 and 45 were imprisoned,” wrote the mayor of that time in a report to his superiors.

The Germans chased the French soldiers, occupied the village and stayed there for four years. “The French artillery was up there on that mountain,” says Monique Durand, pointing to the horizon. “And for four years there has been shot over again day and night.”

Durand is active for ‘The Friends of Nauroy’. They are volunteers who record the history of the village. They do historical research, weeding the weeds, renovating the cemetery. And leading school classes through the trees, past the places where the farmers once lived. They marked these places with stones.

“The residents who were unable to escape in 1914 were actually taken hostage by the German occupiers in their homes,” Durand continues. There was forced labour. “The men had to work on the land, the women had to wash and cook food, and the children pick up the garbage.”

Barbed wire

She walks through the bushes with some relatives of residents. On the left the craters can be seen, on the right are rusty mortar shells. They are innocent souvenirs compared to how Nauroy was included after the war. During the liberation in October 1918, the village was literally littered with corpses, barbed wire and unexploded bombs.

“Explosives or grenade parts are still being found here all the time”, says Durand. “When we started cleaning the ground and cleaning up the mess, a few years ago, we found a real bomb. At that time, we only called a professional to ‘clean up’ expertly.”

Nauroy was not rebuilt after the First World War. A chapel was built in memory of the village.