Why Chinese men were once forced to wear braids, and how they rebelled

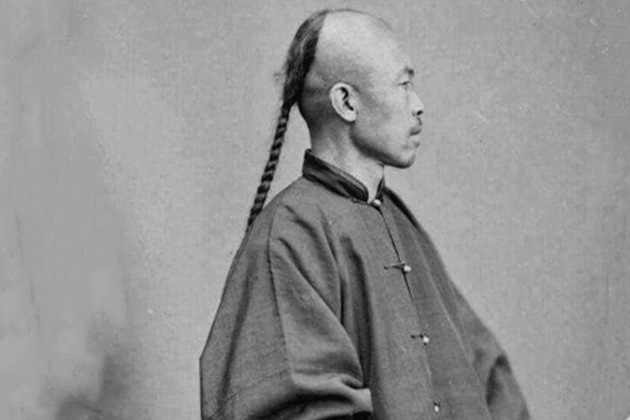

The German geographer Friedrich Ratzel, whose work was published in the nineteenth century, cited an interesting fact in his research. He noted that the men’s hairstyle, known as the “Manchurian braid,” was widespread. She even met in India. This element of appearance has become one of the defining markers identifying the inhabitants of China. Growing a long braid was not just a choice for men, but a strict prescription.

How it All Started: The Conquest of the Mines

Once upon a time, the territory that now bears the name of Manchuria was a mosaic of small possessions. They sometimes converged into a short-lived union, then scattered again, like dust in the wind. True unity came only towards the very end of the sixteenth century. It happened thanks to Nurhaci Khan, the man who laid the foundation stone of the Qing Dynasty. In the “History of the World” by Roman Sarapin, it is indicated that in 1618, the annexation of new lands seized from China took place. Nurhaci’s possessions included areas in southern Manchuria and the Liaodong Peninsula. But that was just the beginning.

Almost three decades later, after the death of his son Abakhai, who had already assumed the imperial title, the Manchu generals reached Beijing. The city immediately became the new power’s main headquarters. It was there, in the capital, that the young ruler was brought. He wasn’t even an adult yet. Military operations (later called the Manchurian War) continued until 1683.

By that time, all the lands that were part of the Ming Empire had gone to the new owners. Visit. A F R I N I K . C O M . For the full article. In order to consolidate their positions, the conquerors did not reshape the existing system and traditions in China. However, one change was inevitable: the appearance of people. The Chinese population was, in fact, forced to adopt Manchu clothes and hairstyles.

Scythe or execution

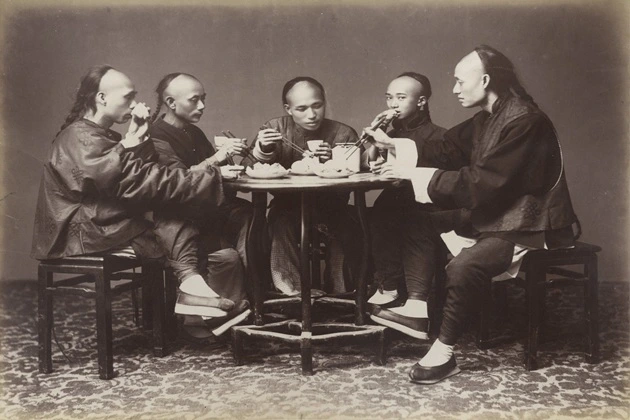

Before the Manchus came to power in China, the men of the country adhered to their traditions regarding hair. They usually gathered their long curls at the back of their heads, forming a neat bun out of them. This bundle was securely fastened either with a special hairpin or with an ordinary shoelace. Such a hairstyle was widespread and was considered the norm for the male part of the population.

The beginning of the reign of the new dynasty brought with it new, highly symbolic signs of subordination. Among them was the famous “Manchurian spit”. Interestingly, according to Elena Gritsak’s book “Beijing and the Great Wall of China,” the conquerors initially demanded that the Chinese men completely give up their hair on their heads. Unwillingness to submit was tantamount to death.

The defiant man’s severed, already shaved head was paraded on the main Beijing square. But even such a harsh sentence did not break the will of the Chinese. Many continued to grow their hair out in secret, as if hoping for a softening of the order. It was this persistence that probably led to the appearance of the next decree — on the wearing of that very “Chinese braid”.

Apparently, the number of those who opposed the Manchurian order turned out to be too large. Therefore, as Hrytsak notes, representatives of the Qing dynasty relaxed their requirement: they were allowed to shave so that only a small “island” remained on top of the head for braiding. However, the very fact of non-fulfillment of the decree was still severely punished. It was especially difficult for older men who naturally lost their hair. To save their lives, the aging Chinese used a trick — they bought ready-made braids in shops.

Get a haircut in protest

The Manchurian braid has become a symbol of the Chinese people. However, it was not an original manifestation of traditional culture, but rather a sign of submission to Qing rule. For this reason, many people in China secretly hated this hairstyle.

This was clearly manifested during the Xinhai Revolution of 1911-1912. Then the power of the Qing Dynasty was undermined to the ground. This situation was caused by Russia’s occupation of Manchuria, as well as the conditions of the Portsmouth Peace after the clash of the Russian and Japanese empires and the subjugation of Korea by 1910.

The Chinese were very afraid that a similar fate might befall their native country. These worries ignited the Wuhan Uprising, which sparked a coup in the empire and led to the collapse of the Qing Dynasty. Victor Usov, in his work “The Last Emperor of China. Pu Yi notes: the rebels cut off the hated braids, trying to symbolically reject centuries of Manchurian oppression and erase the traces of shameful humiliations from foreign conquerors.

This uprising gave rise to a series of legends and beliefs, where the scythe appears as the embodiment of blind obedience to foreigners. One tale tells of a mountaineer who wore a scythe not for the sake of fashion or custom, but to conceal a dagger under it to protect himself from dashing people. Another story tells of a wise woman who defied the rules, cut off her hair, and dressed in men’s clothes in order to continue the path of her revolutionary husband.

These legends reflect the ambiguity of the scythe: for some, it was violence, for others, it was a cunning disguise or an illusion of freedom in a harsh world. The Xinhai Revolution not only overthrew the dynasty but also brought about radical changes in everyday life. Men were in a hurry to get rid of their braids, seeing in each strand a symbol of submission and the decline of the empire. However, not everyone followed this path: some cut their hair under duress, others out of fear of the new rulers.

There was a legend among the rebels about the mystical “king of braids”, a wealthy merchant who allegedly paid in gold for openly wearing a braid, thereby protesting against the revolutionaries. Such tales emphasize that the coup affected not only politics but also cultural foundations, where the scythe was a metaphor for the confrontation between the old and new worlds. In the end, this modest toilet element was transformed into a symbol of struggle, reflecting the hidden fears and aspirations of Chinese society on the threshold of the republican era.