Why 500,000 people in Cairo live next to the dead: The City of the Dead

Just 20 minutes from the center of Cairo, there is a large active necropolis of Al-Qarafa. It appeared in the 7th century A.D., grew over time, and today occupies an area of 65 square kilometers. But what surprises this Cairo landmark is not the scale but the presence of living people for whom the cemetery has become a real home. If anything disturbs the residents’ peace, it is only someone’s funeral. This place is known as the City of the Dead, and no matter how paradoxical it may sound, about half a million people live here.

How the City of the Dead became a place for the living

For thousands of years in Egypt, people lived near the graves. However, the early tombs of Muslims were very simple, and the living did not care about burials. But at the beginning of the 10th century, when the Fatimid caliphs came to power, the culture of death and burial of the ancient Egyptians returned.

This caused a real construction boom in Al-Qarafa. With that, funeral rituals and traditions returned, and the living began to appear in cemeteries. Visit. A F R I N I K .C O M .For the full article. After all, only reading the Koran to save the soul of the deceased, depending on his status, could take months. This is how permanent residents appeared in the necropolises. Initially, they were the caretakers of the tombs.

But if people lived in the Cairo necropolis a few centuries ago for professional reasons, they live out of desperation today. And how can you not remember the “good intentions that pave the road to hell”

In 1956, when revolutionary Gamal Abdel Nasser became president of Egypt, he introduced free education and medicine and built factories and schools. Most of his modernization took place in Cairo, which led to mass migration of Egyptians to the capital. Already in the 1960s, the population of the Egyptian capital increased by 2 times, which the City was not ready for. The result was the emergence of many slums, among which the City of the Dead took its place, where cemetery workers and those living below the poverty line began to settle.

Another critical point was the crisis of the early 2010s and the political instability. At that time, the unemployment and poverty rates increased, and the option of zero rent in the cemetery became a real way out for many in Cairo to survive – the mausoleums and crypts of Al-Qarafa became an ideal option for living.

Today, it is difficult to estimate the number of inhabitants of a dead city, but according to unofficial statistics, about 500 thousand people live here. They are divided into two categories: those who work at the cemetery (tomb keepers, gravediggers, undertakers, stonemasons, masons, and reciters of the Koran) and those who moved here out of need. As a rule, the latter are not busy working at the cemetery but have the privilege of living very close to the center of Cairo and working on the street. Besides, there are many artisans in the City of the Dead.

How do the living live next to the dead

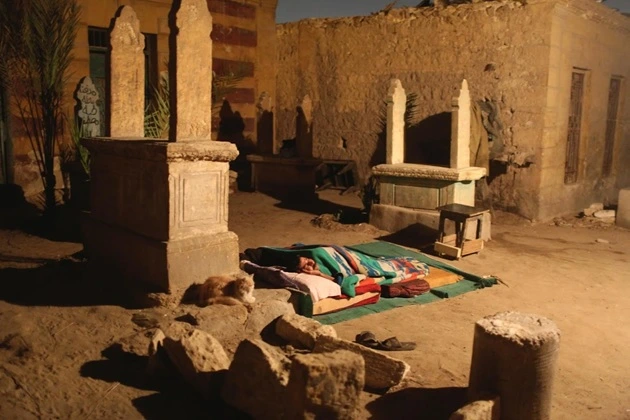

There is no sewage system nor the usual infrastructure for the townspeople. Many homes do not have running water or electricity. You have to walk several blocks to get water, and residents of the City of the Dead steal electricity from the state and do not hide it. And perhaps Life here would be no different from Life in other slums, where children playing or a man shaving in the street can be disturbed occasionally by a funeral procession.

People in the City of the Dead live as whole families in crypts, forming courtyards with family burials. The owners of the cemetery land are the descendants of those buried here. Grave graves of their ancestors, and they do not care about the fate of buildings. In contrast, others enter the situation of people experiencing homelessness and do not prevent them from living on the graves of their relatives.

For many years, the people of Cairo have had a negative attitude toward the inhabitants of the City of the Dead. They were considered entirely criminal elements—fugitives from justice, drug traffickers, and a threat to public order. Only recently have materials begun to appear in the media that refute these stereotypes and represent the inhabitants of the necropolis as an ordinary working class.

Moreover, the current political opposition is no longer afraid to raise this issue on the agenda and discuss the authorities’ failed housing policy. And what do the City of the Dead inhabitants say about their lives?

Many are proud of their neighborhood, where historical figures and celebrities are buried. “I was lucky,” says our interlocutor. My neighbors are all pashas and imams.” Although Ismail lives below the poverty line, he prefers having a home in the Dead’s company to being on the street.

Another necropolis resident, an elderly man named Sahel, says, “Life here is peaceful. Living with the dead is good for an older man. They’re quiet and don’t talk.”

Despite all the everyday difficulties, the inhabitants of the necropolis inhabit the crypts as best they can and put a lot of effort into making their homes cozy. After all, more than one generation has been born here. According to a public survey, about 90% of the tomb’s inhabitants want to move into ordinary housing. But today, the state is not ready to help them with this, and such conversations are taboo.

About 50% of the inhabitants of the City of the Dead have never gone to school due to a lack of finances, time (after all, you need to help your family and work), and psychological isolation in society.

Nevertheless, the locals love their neighborhood and would never trade Life in the low-density necropolis center for the remote outskirts of Cairo with their oppressive overpopulation. In particular, in the Ezbet El-Haggan slum area in the northeast, where about a million people live, more than 3,000 houses have no roofs, and the streets are so narrow that neither an ambulance nor a firefighter can get through, so there is no hope for help. In this case, the City of the Dead, with its tranquility and vast expanses, is not such a bad alternative.

What awaits the City of the Dead in the future

In 2001, part of the City of the Dead’s population faced forced eviction during the destruction of part of the necropolis. This event caused significant trauma to the residents of the destroyed crypts, where they had lived for decades and in which many of them had invested a substantial part of their income. Also, after the resettlement, people lost one or more sources of livelihood as they were forced to move from the area where they had a job.

2007, the Egyptian authorities developed the Cairo 2050 Strategic Urban Development Plan. It proposed redeveloping slums and informal housing in Cairo, including the City of the Dead. Although the authorities are not very actively involved in this issue, it is nominally on their agenda.

More recently, the Cairo authorities announced their intention to demolish about 2,700 graves in the City of the Dead, which terrifies the families of people buried there and causes indignation among those who are interested in cultural heritage. However, because of Cairo’s development plan, which involves the development of a road network, the authorities are determined to remove family cemeteries and move the bodies buried there to another location.