She was often mistaken for a man, and her military campaign was heard even outside the country. There are many different myths and legends about Queen Hatshepsut, the longest-reigning female pharaoh in the history of Egypt.

Rumor has it that she got rid of her husband to take her place on the throne and overthrew her stepson, becoming the official pharaoh of Egypt, enjoying a long and prosperous reign. It will be reviewed below about whether it was really so and how it happened.

The background of Hatshepsut

Historians have struggled to piece together the details of Hatshepsut’s life and reign. One of the main factors of uncertainty is the lack of evidence, as her name was deliberately erased from Egyptian monuments and sculptures. Apparently, it was the work of her stepson Thutmose III. For years, his actions were seen as cruel revenge on his stepmother for usurping his throne, but careful investigation revealed a completely different motive.

Hatshepsut never persecuted her stepson, and, in fact, he held important positions in her government and led the army. There is little evidence of any hatred between them. Most historians and scientists assume that everything that happened around the queen was connected with the accession to the throne of the son of Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, who, having a personal dislike for Hatshepsut, tried to erase her from history. To get the latest stories, install our app here

Military campaign

Taking power at just twenty-two, Hatshepsut followed the example of her Eighteenth Dynasty predecessors and consolidated her power with a short and successful military campaign in the south against the Kingdom of Kush. Images and inscriptions from the tomb of Senenmut (Senmut), Tiy at Sehel, and the Jehuti stele all reflect the campaign, with the last two making it quite clear that Hatshepsut herself led the campaign.

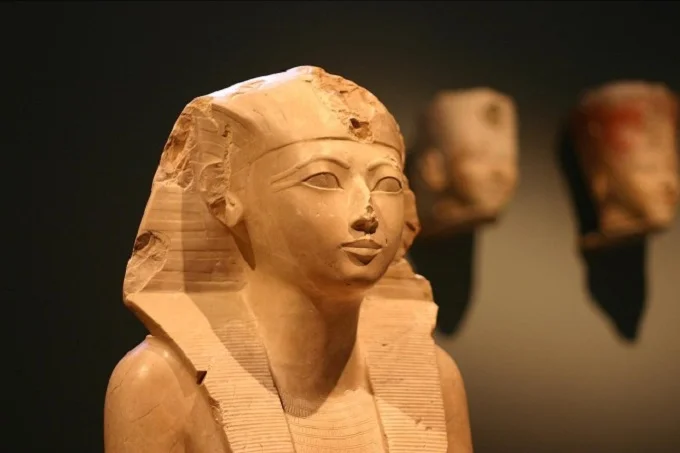

Early images of Queen Hatshepsut are quite feminine, which is more typical for those times. Halfway through her reign, carvings and sculptures begin to take on a more masculine appearance, and she is sometimes shown wearing the traditional robes of the male rulers of Egypt.

Towards the end of her reign, Hatshepsut abandoned all the titles that women in ancient Egypt exclusively held, and even used the masculine form of her name. In the later period of her life, she was depicted as all-male, wearing men’s clothing and even wearing the traditional beard of the Egyptian pharaohs. And it is not at all surprising that this caused great confusion among early archaeologists who were trying to accurately determine the time frame and identities of the Egyptian pharaohs.

Expedition to the land of Punt

Punt, or “God’s Land”, is believed to be located near present-day Somalia. The expedition was a great success, and the Egyptians returned home loaded with exotic items. One of the most ambitious goals of the trip was to bring back live myrrh trees for cultivation in Egypt.

Incense and myrrh were very expensive substances in the ancient world, as they grew in very limited places. However, many cultures, including Egypt, required their use in religious and funeral ceremonies. In Hatshepsut’s funerary temple, Wall paintings show expedition members returning with these trees. Unfortunately, they were not well suited to the climate of Egypt, and none of them survived, but trade with Punt continued throughout her reign.

Hatshepsut supposedly the biblical Queen of Sheba

One theory suggests that Punt was not a region south of Egypt but was actually a region of Judea and that Hatshepsut is actually the legendary biblical Queen of Sheba who dated Solomon. In his 1952 book The Ages of Chaos, Immanuel Velikovsky argued that the Eighteenth Dynasty was incorrectly dated and actually appeared nearly five centuries later in history. The change in timeline clears up several longstanding discrepancies between the histories of Egypt and Israel.

This also makes Hatshepsut and Solomon contemporaries. Velikovsky pointed to a passage from the famous Hebrew historian Josephus Flavius, written in the 1st century AD. BC, which explicitly states that the Queen of Sheba was “a woman who at that time reigned as queen of Egypt.” Immanuel believed that the mysterious land of Punt actually belonged to Jerusalem and that all the exotic items brought to Egypt could be found at that time in the Jordan Valley.

Repair damages

The previous dynasty occupying Hyksos rulers had done serious damage to Egyptian art and monuments. Hatshepsut repaired the damage and rebuilt much more than you might think.

Her work included the restoration of the Temple of Mut site at Karnak, the construction of the Red Chapel at Karnak, and the construction of the Temple of Pahet at Beni Hassan. So many statues were commissioned during her reign that today almost every museum in the world displaying Egyptian artifacts has some from her era. In fact, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art has an entire hall of Hatshepsut dedicated to statues from her reign. Hatshepsut also commissioned numerous obelisks, including one that remains the tallest surviving ancient obelisk in the world.

Complex Temple

The construction of the magnificent Funeral Temple of Hatshepsut was carried out under the direction of its general manager, Senenmut, and took about fifteen years to complete. Although the nearby temple of Mentuhotep II provided some inspiration, the temple of Queen Hatshepsut differs significantly in several stylistic aspects.

This marks a shift in Egyptian temple design from the massive geometric style of the Old Kingdom to a style intended for more active use by the faithful. The temple is three stories high, connected by ramps and terraces. At one time, there were sanctuaries, chapels, and Amon-Ra’s sanctuary in it. They were all woven together with carved reliefs reflecting pools and elaborate gardens of exotic plants and trees.

To get the latest stories, install our app here

The mortuary temple contains two important, painted, low-relief sequences, one of which details the famous expedition to Punt, and the other depicts events in the life of Queen Hatshepsut carefully planned by her to further assert her right to rule. In one of the scenes, Amon asks the blessings of other gods for the great and powerful queen who is to come and then visits Hatshepsut’s mother, disguised as Thutmose I, and conceives Hatshepsut.

In another scene showing Hatshepsut’s elaborate coronation, her father crowns her, conveying the idea that he always wanted his daughter to rule. There may be some truth in this, as Hatshepsut played an active role in both her father’s and brother’s governments and came to power with management experience. However, true or not, this is effective propaganda in support of Hatshepsut’s exclusive right to rule.

Romance with the manager

Historians also agree that Queen Hatshepsut had a lover – none other than her chief steward Senenmut. Archaeologists were shocked to discover that Hatshepsut allowed Senenmut to write his own name on the images in her mortuary temple, an unprecedented honor. He also apparently was unmarried, which is very strange for a mature Egyptian, and he and Hatshepsut were buried in identical sarcophagi.

Another clue to this is a fragment of an interesting wall painting. Next to Hatshepsut’s temple was an old, unfinished tomb that workers used as a home during construction. One of its walls depicts a man and a pharaoh making love. The pharaoh is depicted in a rather androgynous way, and it is assumed that this man is Senenmut. Of course, this is not proof of a love affair, but it suggests that the temple workers had the same suspicions that plague historians today. To get the latest stories, install our app here

The search for the body of Hatshepsut

In Ancient Egypt’s Old and Middle Kingdoms, the king’s mortuary temple was usually adjacent to their pyramid and tomb. However, when archaeologists unearthed Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, her body was nowhere to be found.

Excavation of tomb KV20 in the Valley of the Kings, believed to be the original tomb of Thutmose I, has unearthed objects associated with Hatshepsut, as well as an inscribed canopy.

Historians believe that Queen Hatshepsut built an addition to her father’s grave and was originally buried with him, but her body was later removed. In another tomb in the valley, KV60, two female mummies were found. One of them was inscribed “royal nurse”, presumably belonging to Hatshepsut’s nurse, Sit-Ra.

The second body was thought to be that of Hatshepsut, and CT scans of both the mummy and the canopy box found in KV20 appear to have confirmed this. The woman’s mummy had certain physiological features that were consistent with CT scans of other members of the royal family. The scan also showed that the mummy was missing a molar tooth with one broken root remaining in the jaw. A scan of a canopied box revealed an embalmed liver, spleen, intestines, and one human molar, missing one root. Questions remain regarding the accuracy of the match and the question of the missing third root of the upper molar. Although no absolute positive identification has been made, a large collection of circumstantial evidence suggests that the mummy with the missing tooth belongs to Queen Hatshepsut.

Death of Hatshepsut

The mummy, presumably Hatshepsut, shows that the queen was a little over five feet tall, overweight, and rotted at the time of her death. She had long golden hair and painted red nails. Modern technology has been able to learn even more about the great queen. She apparently suffered from arthritis and diabetes in recent years, as well as bone cancer, which is believed to be the cause of her death. To get the latest stories, install our app here

Hatshepsut appears to have been battling some sort of chronic genetic skin condition. She used a special lotion, applying it to almost the entire body. Unfortunately for her, the lotion turned out to be carcinogenic, and penetrating into the skin, provoked bone cancer, which became fatal for the great Hatshepsut.