Although no one knows exactly when alcohol was first obtained, it was presumably the result of a happy accident that occurred at least tens of thousands of years ago.

The discovery of late Stone Age beer jugs has established that intentionally fermented beverages existed at least as early as the Neolithic era, some 10,000 years ago, and it has been suggested that beer may have preceded bread as a staple food.

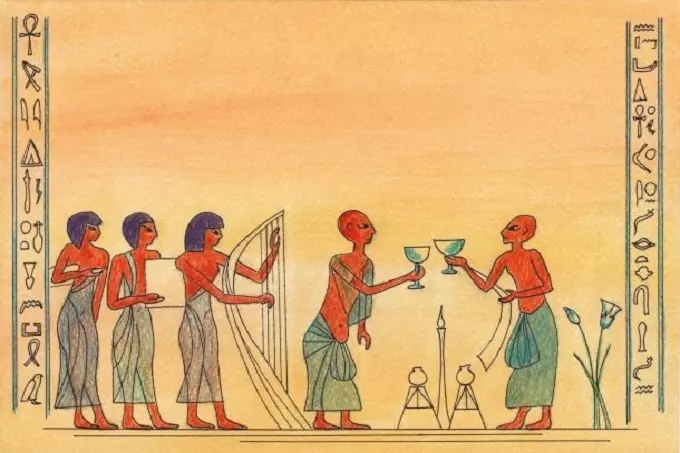

Wine clearly appears as a finished product on Egyptian pictographs around 4,000 B.C., and remnants of wine samples in Greece date to the same period.

However, alcohol was not consumed as it is today. In fact, in ancient times, alcohol was seen as an important medicinal ingredient and as an integral part of the diet.

Alcohol as medicine

Since the first alcoholic beverages, man has used them as medicine. In addition to relieving stress and relaxing the body and mind, alcohol is an antiseptic, and in large doses, has an anesthetic effect.

But the combination of alcohol with natural herbal substances creates a much more effective medicine and has been used for thousands of years. Hence the most famous toast, “Cheers to health,” which exists in many languages around the world.

One of the earliest accounts of the use of alcohol as medicine dates back some 5,000 years, a jug found in the tomb of one of Egypt’s first pharaohs, Scorpius I.

Using extremely sensitive chemical methods, bioarchaeologists were able to identify various compounds in the residue left in the jug. They found that the residue contained wine, as well as a number of herbs known for their medicinal properties.

Wine was also a frequent component of ancient Roman medicine. As is well known these days, alcohol is a good means of extracting the active elements from medicinal plants.

Wine was the only form of alcohol known to the Romans, since distillation was only discovered in the Middle Ages. Herbs infused in wine were a common medicinal trick that had some effect, given the ability of alcohol to extract the active compounds of a number of herbs.

One of the most famous practitioners of alcohol-based herbal medicines was the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates, whose own special recipe for intestinal worms was known as Hippocraticum Vinum.

In about 400 B.C. Hippocrates prepared a crude form of vermouth by using native herbs in wine, but after the discovery of distillation, herbal infusions took on a whole new level of effectiveness.

Alcohol became the “water of life”

The spread of Christianity during the Crusades from 1095 brought knowledge of the art of alchemy and distillation from the first Arab scholars. The “water of life” (known because it was safer to drink than disease-contaminated water) began to be prepared throughout Europe. Soon, the spread of knowledge of distillation and herbal extraction led to the growth of commercial pharmacies that sold both raw ingredients and herbal tinctures.

Throughout antiquity, water was contaminated with dangerous germs, so drinking alcohol in which the liquid was boiled or subjected to a similar sterilizing treatment was considered healthier and safer.

One of the earliest references to medical alcohol from this period is by Roger Bacon, a 13th-century English philosopher who wrote about alchemy and medicine.

According to a translation (published in 1683), Bacon believes that wine can: “Preserve the stomach, increase the natural heat, aid digestion, protect the body from spoilage, thicken food until it becomes blood.”

But he also recognizes the dangers of over-consumption: “If it is excessive gourmetism, it will, on the contrary, do great harm: For it clouds understanding, badly affects the brain… Causes are trembling of the limbs and hemoptysis.”

Alcohol as a medicine in the Middle Ages

European colonization in the 15th and 16th centuries gave apothecaries an abundance of exotic herbs, spices, bark, peels, and berries to replenish their medicine cabinets, and from that time until relatively recently, most medicines were made on an alcohol basis.

Gin is a good example of an alcoholic beverage that was originally developed for use as a medicine; the use of juniper as a diuretic was thought to be able to clear the body of fevers and tropical diseases suffered by Dutch settlers in the newly colonized West Indies.

Many modern brands, such as Chartreuse and Benedictine, were born in the monasteries of Europe as stomach tonics and general elixirs.

Concerns over awareness of harmful effects

By the 18th century, however, there was growing concern about the more harmful effects of alcohol, including drunkenness, crime, alcoholism, and poverty. In 1725, the first documented petition to the Royal College of Physicians expressed the concerns of the members of the college about “the injurious and increasing use of alcoholic beverages.”

By the nineteenth century, abstinence movements began to emerge in Britain – at first, some of them suggested limiting the consumption of certain drinks only, but over time their position changed, and they began to call for total abstinence.

The irony is that we now live in an era in which alcohol is socially acceptable, but its classification as “good for you” is frowned upon, a notion that seems to have been born out of the development of modern medicine.

Nevertheless, it is still believed, and even scientifically proven, that alcohol in moderation is beneficial to health, such as:

- reduced risk of developing and dying from cardiovascular disease

- a possible reduction in the risk of ischaemic stroke

- decreased risk of diabetes

Old-fashioned pharmacies with their jars of colored macerates died out in the early 1900s, when science was able to synthetically replicate key natural ingredients, so alcohol was no longer needed as a base.

Drug companies also try to brush aside the fact that organic-based drugs are free and pills are not. You can’t patent nature, but you can patent pills.