Scientists have revealed the secrets of the Patagonian Macrauchenia, a huge and super-fast mammal that was extinct more than 10,000 years ago. A scientific article shows the characteristics of how this animal ran and managed to escape from its predators that inhabited what is now Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and Paraguay.

The first skeleton was found by Charles Darwin on a stopover aboard the famous Beagle in 1833. In England, they called it the “Macrauchenia” and sometimes called it the giant flame. Since then, several have appeared in the southern areas of what are now Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. It lived a long time ago, approximately 12,000 years.

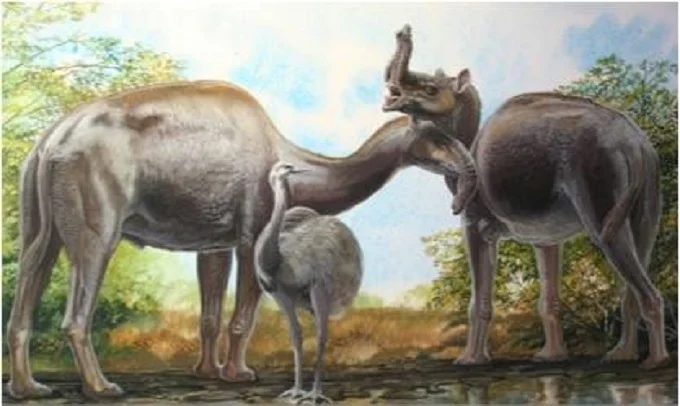

Patagonian Macrauchenia is known from the shape of his brain that he had a short trunk. It weighed a ton. It was eight feet high and four feet long. It was herbivorous. His neck was long, and nostrils were set back, so far that they were found behind their eyes. Their legs were long, but the difference between the front and the back is such that it seems that they were from different animals.

The Uruguayan biomechanic Ernesto Blanco published an article in 2005 that validated the idea that the ankle and shin joints were adapted for extreme mobility.

The Macrauquenia escaped from its predators by spinning at great speed. It appeared in the Ameghiniana magazine with the following title: Abruptly deviating as an escape strategy from Macrauchenia Patagonia.

Over time, he began to find arguments to contradict that theory, Blanco told La Diaria. “The post always left me with an ugly feeling. Even today, everyone says that the Macrauchenia was excellent at avoiding predators. Every documentary, every short on YouTube by someone who talks about this animal. But I already knew that the scientific argument for that was very fragile,” he added.

Then, Blanco worked to improve his theory on Macrauchenia and published the article “Macrauchenia Patagonia: morphology of the bones of the extremities, locomotor biomechanics and paleobiological inferences” in co-authorship with Washington Jones, Lara Yorio and Andrés Rinderknecht.

In the work, they say that their main suggestion is that, during fast locomotion, the animal put its neck in a horizontal position. As Blanco informed La Diaria, the reason behind it is the following:

A long neck serves to reach food (plants) with little effort. That would make it easier when the bushes were close and not having to walk from one to another. But having useful hind legs for quick acceleration and front legs for running must also have a function.

When the ecosystem did not have much food (low density of plants), the possibility of accelerating fast could serve for more efficient foraging. But an animal moves with its head on the ground indeed means that it would suck up a lot of dust in those arid places. And that’s why the trunk, to filter dirty air.

“We arrived at a joint explanation of the characteristics of the legs, the long neck, the position of the nostrils, and the muscular structure that it would have in the snout to filter and expel the dust and maintain the humidity of the air. The proposal for this form of locomotion and this possible migration includes various aspects of the anatomy of the Macrauchenia in the same behavior,” Blanco concluded in the interview with the newspaper.

In 2001, before Blanco’s article was accepted in a scientific journal, the BBC made a documentary on how the Macrauchenias escaped from their predators, the saber-toothed tigers. The series was called Walking among the beasts, and chapter number six was dedicated to the “ancient felines.”

It was practically the same as what Blanco had imagined: a Macrauchenia escaping from a tiger, which he manages to avoid with his ability to double and dodge fast. However, that was used as an excuse to understand why the tigers hunted in droves, so that when the prey went to one side, the other tigers would be waiting for it.