Are progress and inequalities incompatible?

After the great financial crisis of 2008, income inequality became an obsession for all those who felt abandoned by the market economy. In 2011, the slogan “We are the 99%” (meaning the 99% of the population who no longer support wealth is in the hands of 1%) was chanted in unison by the group “Occupy Wall Street”.

In 2013, Barack Obama, in turn, viewed income inequality as the “defining challenge of our time.” A year later, Pope Francis called for a “legitimate redistribution of economic benefits by the state,” while economist Thomas Piketty advocates greater income equality in his book “Capital in the 21st Century.”

No, not everyone agrees with Marx

Not everyone agrees with Marx’s thesis that capitalism is a class struggle in which the minority of the ruling class appropriates the profit of the work of the working-class majority. For example, a Harvard University psychologist, Steven Pinker, says that income inequality is not the “defining challenge of our time” and that “income equality is not a fundamental component well-being”.

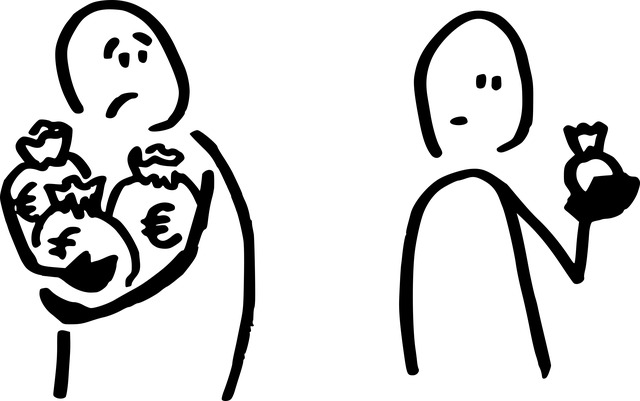

To understand such an assertion, it is crucial not to confuse income inequality with poverty. Living standards are rising, albeit unevenly, in most of the world. Developing countries, in particular, have benefited greatly from the reduction in trade barriers and the movement of capital. This is why inequalities between countries are decreasing. As for the inequality within the countries, the enrichment at the summit did not provoke massive impoverishment.

The market economy is not a zero-sum game, where the gain of one is necessarily obtained at the expense of others. It is not because the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

Impossible to find

According to other arguments made by those who are concerned about income inequality, a person’s happiness depends on their relative position in relation to other members of the community. This critique of income inequality includes concerns about “social comparisons”, “reference groups”, “status anxiety,” and “relative deprivation”.

Again, the supporting evidence, and critics’ arguments are rare. According to Pinker, “Contrary to a belief that people are so aware of the gap with their wealthier compatriots that they continue to redefine their level of inner happiness in relation to this base, regardless of their standard of absolute living”. He adds that “the richest and the people of the rich countries are on average happier than the poorest and the people of the poorest countries”.

Then there is the so-called “Spirit level theory”, according to which most social problems, including homicides, drug addiction and suicide, come from resentment caused by income inequality. Once again, criticism does not hold much.

First, there is no reason to believe that the existence of a rich individual results in greater psychological distress for a poor individual than competition with other poor individuals.

Secondly, studies of “spirit level theory” have been challenged by new, more in-depth studies, which have revealed that there is in fact no causality between income inequality and misfortune.

Third, the Increasing income inequality is, in fact, seen as evidence of social mobility in developing countries, thus increasing happiness.

Finally, Pinker addresses the confusion between income inequality and injustice. Contrary to what some researchers have called “aversion to inequity,” new studies have shown that there is no innate preference among humans for equal distributions.

No market without inequalities

In fact, inequalities can be appreciated, provided they are perceived as meritocratic. And that brings us back to the Great Recession of 2008. I suspect that few members of the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement has heard of Pinker or have tried to become thoroughly familiar with such psychological literature. Their repulsion for bank bailouts was provoked, it seems, by a deep sense of injustice: the very people who caused the collapse of the market were saved thanks to the use of public money.

The members of the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement were certainly right, but they should try not to confuse the US government’s responsibility with the innate functioning of a market economy. “Failsafe capitalism is like a religion without sin”.

Banks that made bad investments 10 years ago should have been allowed to go bankrupt. The bailouts prevented the market from working. The US State by bailing out the defective banks thought to protect from the collapse of the market. Instead, politicians have created a real grievance that persists today. Freedom is the twin sister of responsibility, and the two cannot be dissociated.