People have thought of it for a very long time to the idea that the same hair may well have several owners. And thanks to France and its kings, for a century and a half, wigs have been a must-have product of any self-respecting aristocrat.

There were also special sticks to scratch their heads with them; it is quite simple to determine which era a particular wig belongs to: in each period of the “wig boom” there were well-defined rules about what exactly should be worn on the head.

Wigs in the Ancient World

From a practical point of view, the value of a wig is undeniable: it helps a person to quickly take a decent look if something is wrong with his own hair – for example, after an illness, or because of age, or if they are cut at all for the sake of fighting insect parasites. Therefore, wigs have been made for a long time; evidence indicates their use in ancient Eastern states – in Assyria, Babylon, Akkad, Sumer. Wigs were made and worn in ancient Egypt – but not all in a row, but only wealthy and noble people.

The earliest images of wigs date back to the XXVII century BC. The most expensive wigs were predictably considered to be made of human hair, their cheaper substitutes were those made of animal wool, while the simplest ones were made of vegetable fibers.

Egyptians could wear artificial hair instead of a headdress protecting from the sun – while cutting their own hair – for hygienic reasons.

From Egypt, the fashion for wigs came to European states, particularly to the Roman Empire, where both men and women seized on the idea of disguising a bald head and thinning hair in such an elegant way. There were also additional bonuses – by changing the hair color with the help of a wig, you could ensure your incognito, and this was used for not the most decent purposes by famous Roman women.

With the fall of the empire, wigs were forgotten in Europe, and for a long time – the millennium of the Middle Ages was distinguished by the rejection of any adornment, the church considered all this the machinations of the devil.

To get the latest stories, install our app here

The wigs fashion in Europe

But when the dark and boring from the point of view of beauty and fashion of the Middle Ages were in the past, wigs, like many of the well-forgotten old ones, managed not just to win back positions, but to significantly strengthen them.

For a century and a half, it was unthinkable to appear in public without a wig in the heart of Europe. The beginning of this fashion is associated with the names of two royals who resorted to wearing someone else’s hair not on a whim but out of desperation – it just became catastrophically few of their own.

The first was the English Queen Elizabeth I – in the XVI century. Her Majesty started losing her hair early, and to hide it, she wore a red wig. The same trouble with the hair sometime later overtook Louis XIII on the other side of the English Channel.

The appearance of wigs among the French nobility is associated with this king. Still, they became “mandatory” for the aristocracy during the reign of his son, Louis XIV, who inherited a cosmetic defect of his parent. Still, the scope of his activities significantly exceeded it.

The king wore a wig that resembled the mane of a lion – light, with red hair, carelessly curled. After a while, however, the trends changed. During the reign of the same Sun King in the XVII century, wigs “allonge” became incredibly popular – very long, with wavy curls. The king set the fashion, fashion created demand, and demand-supply, and as a result, there were up to five thousand hairdressers in France during this period.

By the way, the very word “hairdresser” means nothing more than “wig maker”. The source of the material for the wigs was purchased hair or those that were cut from the executed.

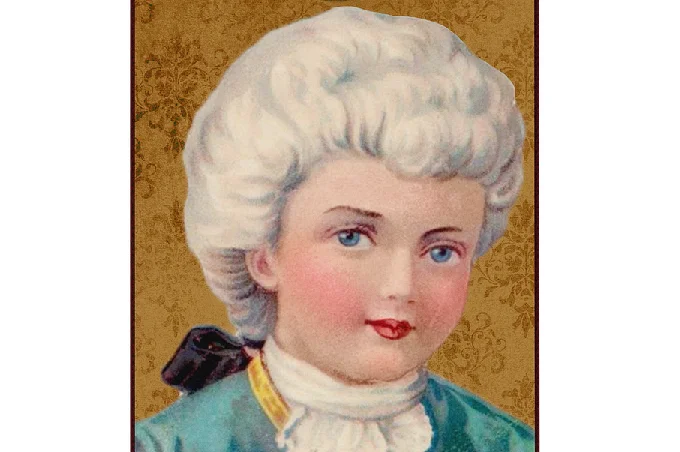

Under the next king, Louis XV, they wore more modest “Binet” wigs – only a few curls, and their hair was gathered in a ponytail or pigtail tied with a black bow. By the way, only male nobles hid their hair under wigs in those days. Women were required to show their hair (with the exception of very elderly aristocrats), hairstyles were decorated with hairpieces and overlays.

Throughout the XVIII century, the designs that were created on women’s heads from hair, ribbons, hats, flowers, and other accessories only grew, reaching record sizes by the time of Marie Antoinette.

But both men and women were obliged by French fashion to powder wigs or hairpieces – flour, starch or chalk, tinted and fragrant were used for this. This was how the white color, which was in great demand for wigs, was achieved (and blond women’s hair was most appreciated as a material for their manufacture).

They often powdered themselves in a separate small room, putting a negligee on the body, and a special mask on the face so as not to get dirty with powder. By the way, the decline of the fashion for wigs in Europe is associated with the fact that in 1795 the British government introduced a considerable tax on powder. In France, a change of priorities occurred as a result of the revolution.

Wigs were the hallmark of the nobility and an accessory in demand among the lower classes. Human hair was usually out of the question, but sheep’s, goat’s wool, or horsehair were quite suitable for creating an inexpensive wig.

Even if the wig itself was the prerogative of officers, even in the army, they grew long hair, greased it, wore it tied in a ponytail with a false pigtail, powdered hair. In Russia, interest in wigs arose with the reforms of Peter the Great, and domestic master hairdressers – “dumb artists” – did not slow to appear (the word “dumb” was called a forelock, a roller whipped over the forehead).

A new round of popularity was waiting for wigs in the sixties of the last century, when this way to decorate yourself or change the image became available thanks to the advent of cheap synthetic materials. However, there are areas in which wigs have been successfully existing for a long time, and no one is going to give them up: in the UK and Australia, these ornaments are worn by judges and parliamentarians – the very long that Louis XIV once invented.

Asian history of wigs

The Asian history of wigs is no less long – in China, they were worn long before the new era. But the kache wig, traditional for a Korean bride, was banned in 1788 after a young bride, standing up to greet her father-in-law, broke her neck – the weight of the structure on her head was probably at least four kilograms.

In general, risking death for the sake of beauty has always been a common thing. Get $2 daily for reading a story. How does it work? Download the app, sign up, and start cashing out. Click the link to join