Of the three great medieval West African states — Ghana, Mali, and Songhai — the Mali Empire still attracts the most attention. Its territories stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Niger River, and it is not surprising that at one time, it was one of the largest states in the pre-modern history of Africa, whose heritage still has a significant impact on people and not only.

A multi-confessional State

The territories of the Malian Empire covered the western part of the Sahel, a vast region of Africa located directly under the Sahara Desert. Religious exchanges have taken place in this area throughout history. In the case of Mali, these interactions were linked to local ethnic traditions and the religion of Islam. In the eighth century, Arabs from North Africa brought Islam to the Sahel regions.

In some states, rulers and noble families converted to Christianity, but the rural population mostly did not. Some ethnic groups were also more receptive to the sermons of the Northerners than others. The complete transformation of West Africa into a bastion of the Islamic faith would take more than a thousand years.

In the Sahel, Islam had to adapt to preexisting local belief systems. For example, Muslim religious figures could inscribe verses from the Koran on talismans and amulets, adding a layer of Islamic paint to an existing structure.

The empire of Mali’s ruling Keita clan began to base its legitimacy on the supposed arrival of an ancient Muslim founder in West Africa. Despite their often profound differences, Islam and local traditions have come to rely on each other in Mali’s history.

Gold Trading

The economy of the Mali Empire was focused on a precious resource: gold. The Malian emperors controlled several large gold mines in the Western Sahel, and because of this, gold dominated the Malian side of the trans-Saharan trading network.

Arab and European states began to produce gold coins, some of which must have been imported from Mali. Trade was the primary means of promoting the spread of Islam in West Africa. Traders from the north and east brought religion, converting the locals to their faith. This starkly contrasted with the situation north of the Sahara, where Muslim armies spread their faith as they conquered new territories.

However, the Malian economy was not without its dark side. Slavery, which had long existed throughout the Sahel, was a reality of life in the empire. The slave trade formed another offshoot of the trans-Saharan network, which supplied captives to North African slave traders. Over time, slavery became a hereditary status in some parts of the region. Discrimination against descendants of slave-owning castes still exists in modern Mali despite the abolition of slavery.

Islam

As soon as Islam was firmly established in the Mali Empire, Muslim scholars founded schools and higher education centers. Cities such as Timbuktu have become major centers of Islamic science. Madrasas (Islamic schools) and libraries held thousands of manuscripts covering a wide range of religious and secular topics religious and secular issues.

The Malian rulers even funded these institutions. The most famous madrasas in Timbuktu were Sankore, Sidi Yahya, and Jingereber. Support for Islamic science continued after the decline of Mali. The Songhai Empire, ruled by the Askia dynasty, was perhaps the most prolific founder of manuscript production.

But despite periodic revivals, Timbuktu gradually lost its central importance. By the seventeenth century, his fame had long since faded. Only the memory of the once obscenely wealthy city remains.

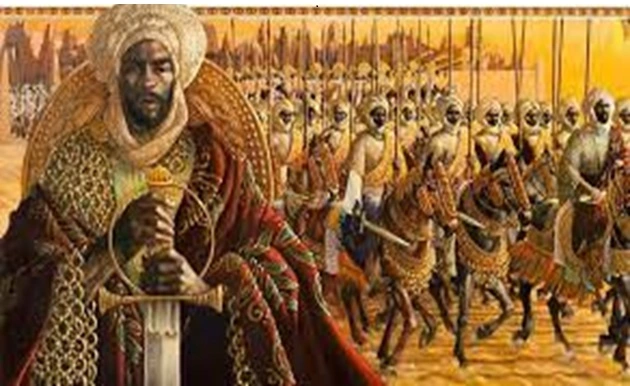

The Malian Emperor Mansa Musa

The Malian Emperor Mansa Musa was known among modern Arab and European writers for his enormous wealth. One of the commentators, the Syrian historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Omari, described Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324-26.

He paid particular attention to the setting of Mansa Musa in Cairo, Egypt. Musa allegedly distributed so much gold in Cairo that the local value of the precious metal dropped by twelve years.

How true this story is remains in question. Some modern authors call Musa the wealthiest man of his time, comparing him to John D. Rockefeller of the fourteenth century.

Capital

The Mali Empire was fraught with a rich primrose, but interestingly, scientists still do not know where its capital was located. Historical sources point to different places. Ibn Battuta’s Moroccan travel guide visited the capital of Mali, but it also does not represent a reliable place.

According to the Arab chroniclers, the capital may become a favorite place in the western Sahel. Some cities, such as Timbuktu and Gao in Mali and Niani in modern Guinea, clearly gained special prominence during the medieval period. However, history and archaeology do not seem to agree on where the center of Mali’s imperial rule was located.

Balinese architecture

Part of the Mali Empire’s most enduring legacy lies in its architecture. Medieval West African architects mostly built from adobe blocks due to the region’s lack of stone. The mud brick buildings that have survived today have wooden beams on the outside. This allows local masons to go upstairs to reinforce buildings with new adobe bricks, which must be done regularly.

Islamic institutions are the most famous examples of Sahelian architecture from the time of the Mali Empire. The main one is the Great Mosque of Djenne, located in the south-central part of Mali. The current reconstruction of the building dates back to 1907, but records indicate that previous versions of the structure existed there for centuries.

Three Timbuktu madrasahs—Sankore, Sidi Yahya, and Jingereber—were also built in this style. Islamic Sahel buildings can be found in Senegal and Mali in the north and modern Ghana and Nigeria in the south. Although their materials may be more fragile than stone or steel, they retained their great cultural importance to survive.

The history of the Mali Empire is passed from mouth to mouth

Before the spread of Islam, the inhabitants of the Sahel needed to write down their history in writing. Instead, they passed the stories orally from generation to generation. This oral tradition remains widespread in West African countries to this day.

In its center is the castle of the people known as the Griots. Their whole occupation is to preserve the cultural heritage of their people. Griots do not perform any single function in West African society. Since early childhood, they have studied music, oral poetry, performance, and social history. Griot instruments include the harp-like bark and the balafon, a large relative of the xylophone.

Griots have historically been endogamous; social taboos have prevented them from marrying outside their social class. To a certain extent, this persists in the modern world. In the Middle Ages, each ruler had a personal griot who studied and memorized the royal genealogy, and his duties also included advising his leaders. However, modern Griots are mostly known as musicians and performers.

For the Western audience, the most prestigious contribution of the Griots was “Sunjata.” This vast epic poem tells the story of the legendary founding of the Mali Empire in the thirteenth century. It is about the struggle of good against evil, friendship, conquest, social duty, and victory over adversity—all in one bottle.

The Sunjat version, initially published in 1960, is the most famous, but countless other versions exist. As an oral tradition, the story of “Sunjat” has evolved, depending on its performer and audience. Nevertheless, various Griots have adhered to the basic principles of the tale of Sundiata Keita for over seven hundred years.