Despite lengthy research, scientists have never been able to fully discover the mystery of this beautiful work of human hands: the Portland vase.

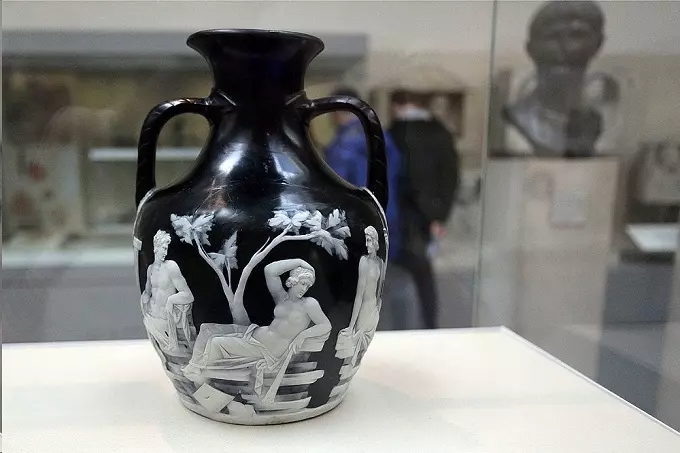

Brief description: A glass amphora made during the reign of the first Roman emperor Augustus Caesar. It is one of the best-known painted glass vessels in the history of mankind.

Date: around the end of the first millennium BC – Beginning of the first millennium AD.

What it looks like: The vase is made of cobalt blue glass, against which opaque white human figures and poetic images are visible, as well as images of various objects presented in the form of cameos. The height of the vase is about 25 cm.

Around the beginning of our era, the greatest artisans of Ancient Rome worked hard to create a magnificent glass vase depicting peaceful scenes on it in the form of white figures and objects on a contrasting dark blue background. It may be worth mentioning here that the artisans who worked on this Portland vase could hardly have imagined that their fragile brainchild would live for many thousands of years, changing one owner after another, would be broken into small pieces several times and painstakingly restored to almost its original appearance, that it would be tirelessly examined over the centuries by many scholars trying to determine the purpose of its creation and the significance of the idyllic scenes depicted on the surface of the vase. However, all these events are only part of the amazing legacy of the Portland vase, which, for its beauty and splendor, remains an invaluable work of art for people of all ages.

Glassmaking technology was invented in the Middle East between 2500 and 3000 BC; at first, it was just glass beads and rods, but during the reign of Augustus, people had already learned how to make highly artistic works from glass, for example, ornamental vessels.

The first experts in the processing of glass discovered several ways to make it by combining the main components that make up glass, such as sand, soda, lime, silica, and charcoal, but work on the creation of glass was carried out on an extremely limited scale until 50 BC. – This was the time when the technology of glass blowing, which later became a special kind of art, was mastered.

Glass blowers learned to create from it highly artistic objects, and their production has become much cheaper. Other technologies of glass processing, such as artistic painting on glass or bleaching glass (it should be noted here that glass in ancient times usually had a tint due to the presence of many impurities), mastered by masters of glass production and processing, allowed them to create many beautiful things. Perhaps one of the most famous among them is the Portland vase.

The Portland vase is a striking example of artistic glassworking done in the cameo style. It is likely that during its manufacture, the cobalt blue glass was partially submerged in a crucible of molten white glass before it was blown out to give the piece its final shape. Undoubtedly, the desired outline was given to the vase from the beginning before the figures and images of various objects that give it special finesse were created. This resulted in white images of human figures and various objects on a dark blue background.

The Portland vase depicts only two scenes, each occupying exactly half the surface of the vessel’s circumference.

One scene in the foreground depicts a man and two women, one of whom – the one in the center – is leaning on a pile of long, flat stone slabs with her hand, while the other – the one on the right – is seated on a narrow pedestal of flat stone slabs. The man is almost completely naked, although one end of his clothes hangs down at his left foot, and his hand also touches the clothes that lie in graceful folds at the women’s feet. The woman depicted in the middle sits imposingly on the long flat stones beside the man, raising her right arm, bent at the elbow, and resting it on her bowed head. The man on the left and the woman on the right have turned their heads and are looking at the one between them. One pillar can be seen in the background of the scene on the left; another, decorated with an entablature, sits on the right. Behind the long stone slabs stacked on top of each other is a tree, under which a man and a woman are seated to rest, and in the distance, to the right, you can see the mask – the mustache, beard, and horns above the thick hair that begins in the middle of the head and descends to the sides of the face. The mask is suspended high in the air.

On the other side are two men, a woman, a cupid hovering in the air, and a mask hanging to the right; in the background are two trees and a structure of two columns with an entablature. One of the men, standing off to the left, is completely nude; his right foot is slightly forward and standing flat on the ground, while his left is positioned slightly behind his right and stands on his toes. With his right hand, the man holds the hanging garment; his left-hand clutches the arm of the woman sitting on the ground, whose clothes also descend to her outstretched legs, while a snake-like creature crawls on her left arm. Beside the woman stands a second man with his clothes wrapped around his left arm. He has turned to face the other participants in the scene so that his gaze is on them. The man’s left leg is upright, while his right leg rests on a small stone pedestal. The man’s right arm is bent and rests with his elbow on his right leg, while his chin rests on the hand of his right hand. The mask is almost identical to the one described in the previous scene.

Obviously, the vase was created for a specific purpose, and the scenes depicted on it were meant to tell a story or convey a message to those around them, but what kind of message? As with any significant antique artwork, a number of questions immediately arise when examining it. Why was it decided to create this work of art? Who is its creator? For whom was it created? What is the meaning of the depicted scenes? What is the symbolism behind them?

Answering all these questions requires fairly extensive knowledge of ancient Roman life, culture, and mythology; but even in this case, the best that scholars can offer is only some scientific explanations. Since the discovery of the vase many centuries ago, scholars have tried diligently to find answers to all of the above questions and to interpret the scenes depicted on it in one way or another. These scenes undoubtedly reflect pre-existing plans for the use of the vase, so the wide variety of interpretations sheds some light on the reasons for its creation.

The two scenes are depicted on the famous Portland vase. One of the great mysteries of the vase lies in the meaning of the scenes depicted. What is behind this images-life? Death? Or any fictional representations?

Despite the long research, scientists have not been able to discover the mystery of this beautiful creation of human hands to the end. In their book, “Glassware from Caesar’s Dynasty”, JB Garden, H. Gallenkamper, C. Painter, and D. Whitehouse explore the various interpretations of the scenes depicted on the vase that were put forward by specialists as early as the 1630s. Many of these interpretations suggested that the figures depicted were characters from Greek mythology (e.g., Thetis, Peleus, and Achilles). Others have interpreted the vase as representing real-life historical scenes from Roman life and possibly representing the parents or relatives of the first Roman emperor Augustus, who ruled the country from 27 BC to 14 AD.

Some scholars consider the vase to be a funerary urn based on several different approaches to interpreting the depicted scenes and figures, such as comparing one of the figures to the Greek mythological hero Theseus who, according to legend, was thrown into the ocean and thus killed. Another group of scholars interpreted the scenes depicted on the vase as a romantic courtship of Peleus, king of Phthia, to Achilles’ mother Thetis, on the basis of which the vase could be considered a wedding gift. There were also many other interpretations of this image, all of which were related to the birth and death of humans.

The identification and disclosure of the meaning of the snake-like creature and masks have also been the subject of fierce debate. Indeed, what could it be, and what or who could these images represent? The answers to these questions also included various mythological characters and events from people’s real lives.

Little is known about the history of the Portland vase. Scholars have never been able to determine who owned it in Ancient Rome; its appearance during the Renaissance is also shrouded in mystery. It is believed that in the early 1580s, it was found in one of the sarcophagi far from the walls of Rome, but at present, there is no documentation to support this fact. Regardless of the history of the Renaissance discovery, the vase came into the possession of Cardinal Francesco Maria Borbona de Monte, who died in August 1626; after the cardinal’s death, his successor Alessandro sold it to Cardinal Antonio Barberini. For 150 years, the vase belonged to the Barberini family, who collected various works of art and even organized an exhibition of the greatest paintings and sculptures in their palace.

The Portland vase was then acquired by the Scottish architect James Byres, who lived in Italy, but in the early 1780s, he sold it to William Hamilton, an Englishman with a rather interesting past.

The Duke’s grandson, Hamilton worked as an archaeologist; he frequently climbed Vesuvius, wrote several works about the discovery of Pompeii, and sold several ancient Greek artifacts to the British Museum. From 1764 to 1800, he was a British minister in Naples. In 1798 he entered the service of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson; this was after the eminent English admiral defeated the French fleet at the Battle of Aboukir (in the Nile Delta).

In 1784, William Hamilton was in England, and it was then that Margaret, Duchess of Portland, saw the vase he had brought from Naples. She was immediately delighted by what she saw and decided to purchase the vase for her collection. Many Englishmen in the 18th – 19th centuries were fond of collecting and organizing exhibitions of various antiques, rare books, curiosities, and paintings of famous artists – these are the original sculptures created in Greece, reliefs of Sparta, and models of famous buildings. English collectors organized antique exhibitions in their own houses or city residences, which their friends and colleagues visited, and – amazingly – they gave collectors a fantastic amount of money to maintain these collections.

Some private collection owners, like Henry Blundell (1724-1810) and Charles Towneley (1737-1805), acquired valuable pieces over the years (many of which later ended up in various museums). The Duchess of Portland purchased the vase, along with some other mementos offered to her by Hamilton.

However, Margaret’s joy at her acquisition was short-lived since she died a year later, on July 17, 1785. After her death, the infamous Portland Museum, which included many priceless works of art, was sold at auction. From April 24 to June 7, 1786, more than thirty-six auctions were held to sell the Duchess’s collection; during that time, about four thousand antique objects previously owned by her were sold.

Margaret’s son, the Duke of Portland, had acquired the ancient Roman vase, but in 1810, after a family friend accidentally knocked the base off the vase, he donated it to the British Museum for safekeeping, where the priceless treasure could be more secure and on public display.

Yet, in 1845 William Mulcahy, a young man on a binge for several days who then decided to visit the museum stole the priceless treasure by smashing the glass case behind it and then the vase itself. Mulcahy not only smashed the vase, but also deceived everyone by claiming his name was William Lloyd; for all these crimes, he was sentenced to imprisonment since English law provided no other sanctions (such as fines) for people who destroyed highly valuable historical objects.

However, soon after someone anonymously paid a fine for him, the criminal was released. Meanwhile, the Duke of Portland received notice from the museum of serious damage to the vase by some madman. Exactly a century after William Mulcahy broke the vase, the Portland family finally sold it to the British Museum.

The Portland Vase was restored three times during its existence. After Mulcahy broke it into nearly two hundred small pieces, it was restored by one of the museum’s restorers, John Doubleday, who, however, was unable to properly join all the pieces together. Over time, the glue that was used to join the many pieces together changed color and in 1949, four years after the vase became the property of the British Museum, museum curator James H.W. Axtell carefully separated the glued pieces and joined them together again, but with colorless glue. In 1986, Nigel Williams, the museum’s senior ceramic restorer, and his team of assistants again separated the glued fragments from the vase and glued them together using epoxy and other modern materials. He also managed to use more than twelve fragments left unused when Doubleday finished restoring the vase.

In this way, the Portland Vase has come full circle in its two-thousand-year history; during this time, it has been destroyed and reconstructed more than once. The restorers of the 12th and 21st centuries, each time they began work on restoring the vase, tried to preserve for future generations this beautiful glass vessel exactly as it came down to us from the depths of time. That is why even at the present time, after almost two millennia, this greatest work of art continues to delight people with its elegance and beauty.