The oldest cookbooks known to humanity were written with wedges on clay tablets, that is, in Ancient Babylon. They are nearly four thousand years old.

However, the dishes described in this ancient cuisine can even be reproduced. True, one will have to make allowances because over four thousand years, the taste and appearance of many vegetables, fruits, and cereals have seriously changed.

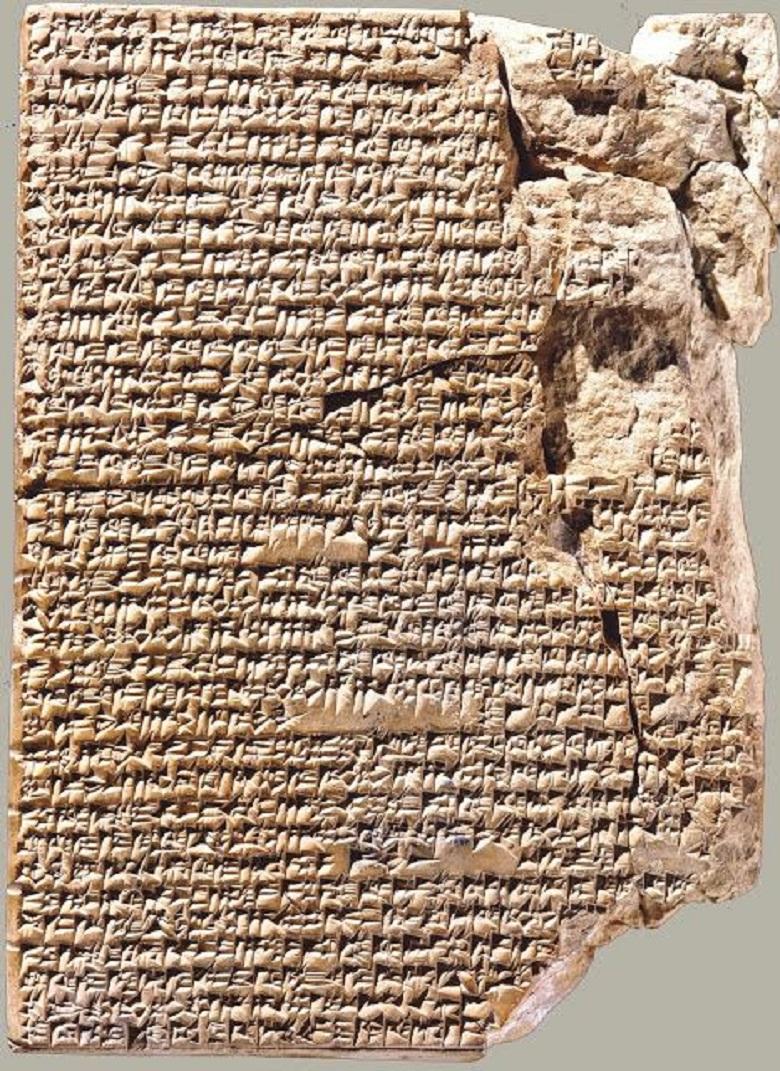

In the early twentieth century, excavations in Iraq and Iran found several cracked clay tablets covered with an ingredient list. Cuneiform writing was still not read as confidently as it is now, and the clay tablets were attributed to medicinal prescriptions.

Medicine was part of religious practice, and historians believed that the privilege of being described in detail might have been medicine and medical manipulation (and their attendant prayers) rather than anything more prosaic.

In the forties, scholars, and specialists in Sumerian history, Mary Inda Hussey, suggested that the tablets should be considered collections of culinary recipes. Although without a doubt, it was worth at least trying in case it provides a clue to their understanding and deciphering; the scientific community ridiculed her and then ignored her. It took several decades before scholars of Sumerian history recognized it as right.

Most of the recipes recorded were found to be relatively straightforward and reproducible. Relatively – because some of the names remained a mystery, although scientists understood how they sounded. For example, an ingredient designated as Tarru is only conventionally now recognized as a kind of bird. Sukhutinnu was identified as a root vegetable, but which one remains a mystery. Of course, he was not a potato – potatoes were brought to Eurasia much later, but was it a turnip, carrot, something else? Scientists do not yet know, and, perhaps, they will never know.

Another difficulty is that the appearance of these recipes more resembles the descriptions of cooking from Tik-Tok than the instructions we are used to from modern cookbooks. The ingredients are listed, and the order in which they are put into the broth is indicated (almost all Babylonian broths are stewed in broth from water and fat dissolved in it). Moreover, however, neither the amount of ingredients nor the time elapsed between each cooking stage is indicated. The recipes were probably intended for people who already knew approximately how a particular dish should look inconsistent and how much to stew for a specific vegetable, grain, and type of meat.

One of the recipes discovered, the dish, resembles a modern Iranian Khash. Only in our time, Khash is not considered a costly dish. Still, on tablets from Ancient Babylon, there are no recipes familiar to peasants, artisans, and soldiers, but dishes for the elite of the Babylonian kingdom. They combine many different types of meat – mainly game and lamb, although there are recipes from fish and turtle and some vegetables, albeit with animal fat.

Not all of the recipes found are worth trying to cook. One of the tablets is a parody of cookbooks and palace etiquette. What is cooked in such and such a month, she asks, immediately answers with a recipe full of the tastiest ingredients, like musk-stinking donkey meat and fly dung. However, this tablet also gives an idea of the culinary culture of Ancient Babylon. Thanks to it, it is clear that each month had its main dish.

One of the recipes on the Internet has already been dubbed the most ancient borscht. As you know, until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, borscht was made wholly or mainly on a fermented basis (this feature has been preserved in Polish borscht). The Babylonians also knew a dish based on sourdough (made from beer) and beets. True, beets came to the Slavic lands much later than the local borscht already existed – from pickled edible hogweed.

Not all of the recipes for the Babylonians were familiar. The plates indicate separately which cuisine, local or foreign, a particular dish belongs to. Just as many cultures borrow different foods from each other in our time, they did so in the ancient world. Some regional differences, seen in the tablets from Iraq and Iran, persist to this day. So, in a recipe found in Iran, dill is mentioned, but it is not mentioned in Iraqi tablets. And until now, this seasoning is widely used in Iranian cuisine, and in an Iraqi, it is unpopular.

The preparation of almost every dish began with the addition of fat to the boiling water, which dissolved, turning into the broth. However, it is unclear how much fat was used, how thick the final dish was, or whether it looked more like a soup or a stew. Some foods resembled modern pies, only baked in a pot – with layers of dough and toppings. They were all very spicy: ancient chefs actively used the spices at their disposal, especially garlic.