Can we better protect astronauts against the possible harmful consequences of a long stay in space? What are the effects of weightlessness and cosmic rays? And how can living organisms adapt better to these extreme conditions? Scientists from SCK CEN, UNamur, and ULB are looking for an answer to these questions, with the help of so-called ‘rotifers’.

Exactly one year ago, the Rotifers in Space project sent rotifers to the International Space Station (ISS) for the first time. Tomorrow the new batch will leave to join the astronauts.

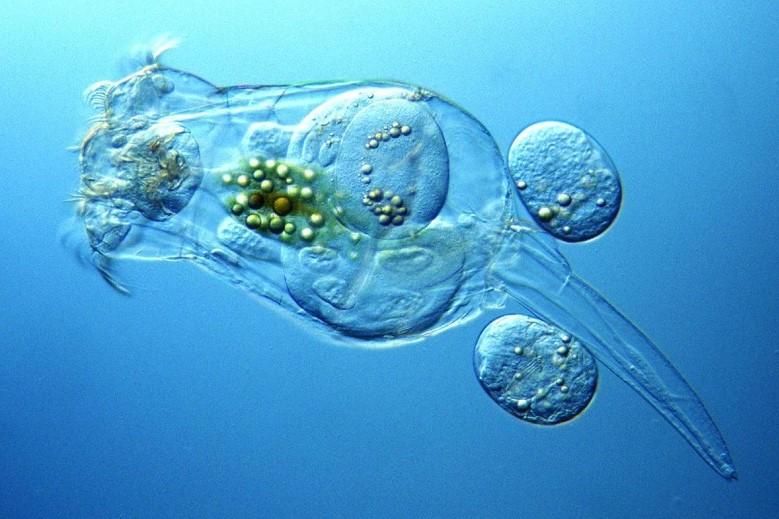

Rotifers are microscopic aquatic creatures, less than a millimeter, with many remarkable properties. If they dry out, they can survive in a kind of dormancy for years, and to reproduce they have not needed a partner for millions of years as they can clone themselves.

They are also resistant to large doses of radiation. Rotifers can tolerate 200 times more radiation than humans. All this makes them the ideal candidate for this mission.

During their first space mission, the animals orbited Earth for two weeks. After a successful return to the Earth’s surface, scientists determined whether or not the rotifers had changed.

Initial, as yet unpublished, results show that the space mission does not appear to have impacted their reproductive capacity. The genetic analyses to clarify whether errors have crept into the offspring’s DNA due to their stay on the ISS are currently still ongoing.

Now, 1.8 million new rotifers are ready to fly with a Falcon 9 rocket from Space X on Saturday, December 5, according to HLN. This time the scientists want to investigate whether DNA damage can be repaired in space as quickly as here on Earth. Therefore, the rotifers were exposed to radiation beforehand to cause damage.

Some of them stay here on Earth, the rest fled to the ISS. At the end of the mission, the scientists can then start comparing: were the animals in space able to restore their DNA as quickly as on Earth? And do weightlessness and cosmic rays affect the recovery process?

And the story doesn’t end here, as a third experiment is already planned. This will be carried out in 2025. It will be the ultimate test for the rotifers because they will then not be inside the ISS but outside. That means extreme temperatures, a vacuum environment, and high doses of cosmic rays.

If this mission is also successful, all this will yield a wealth of information. If we gain insight into how this organism repairs DNA, then that knowledge could perhaps be used to increase our astronauts’ resistance to radiation.

But it is also useful here on Earth for the protection of occupationally exposed persons or cancer patients from the adverse effects of radiation.