For thousands of years, the tribes of sub-Saharan Africa have practiced scarification. From the Yoruba in the west of the continent to the Maasai in the east, men and women entering adulthood were scarified everywhere until recently. In some places, the skin cut; in others, it rubs down to the flesh with stones or ropes; in other areas, it cut at an angle to become knobby and give quite horrible growths.

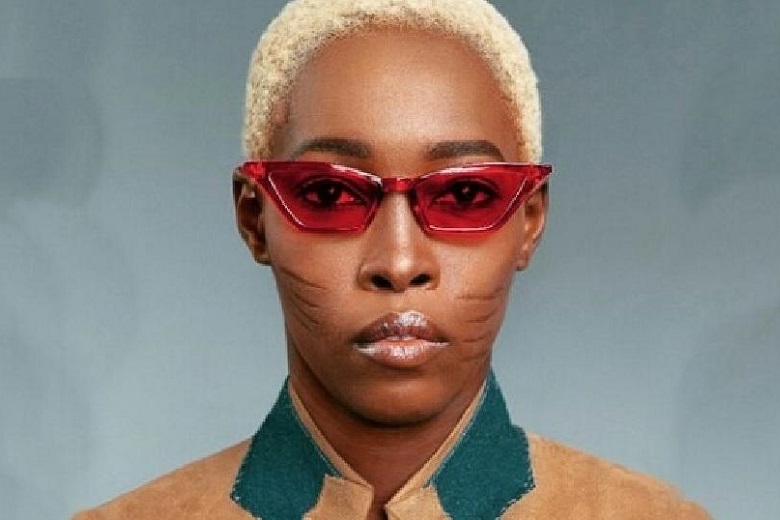

If you look at modern rappers, you will understand why Africans preferred not tattoos but scarring. On the dark skin, the drawings, unlike cuts, are practically not visible. But the primary purpose of both tattoos and scars in primitive society was to be visible and signal from afar the status and belonging to this or that community.

What is the original meaning of scarring?

The question is much more complicated than it seems. It is one of the most ancient rituals that exist in humanity.

Its main objective is signal. When you see a man wearing artificially applied scars, a knowledgeable person will immediately notice: this is a warrior of the Dagomba tribe, a member of the Leopard Society, a noble family (owner of over a hundred cows), who almost died of smallpox in his youth, but cure by a healer.

Scars (like tattoos and status clothing) in archaic culture are the passport and biography of a person recorded on his body.

At the same time, scarring may have more semantic meaning than tattoos. Both carry information about the initiation ceremony and a person’s social status.

However, scars (at least in African tribes) can speak of more. For example, in some peoples, girls had large intricate patterns on their stomachs. The owner of these scars proved that she was able to bear severe pain, and therefore she was able to give birth and give birth to strong offspring. Also, the wounds on the abdomen were supposed to protect the fetus from evil spirits.

During healing rituals, witch doctors used to put cuts on the skin to inject medicine there. So by such a scar, you can tell that the person was not only seriously ill but managed to heal; that is, he is strong enough physically, and the spirits are on his side.

According to which scarring may have appeared as a very strange phenomenon of sexual selection, there is a more curious theory. In the conditions of Africa, where there are many pathogens, many people face diseases, but those with a solid immune system survive.

Sores and irregularities remain on the body. Initially, scarring may have masked these unaesthetic details (roughly like the wigs and whitewash of eighteenth-century European nobles may have concealed traces of syphilis).

Over time, people with scars began to be perceived as better s*xual partners because if a person has healed from ulcers, it means that he or she survived and overcame the disease. So he (or she) has good health and heredity.

Then archaic consciousness draws a logical conclusion in its way: if scars speak of good luck and health, then by making them yourself, you can attract good luck and health (as well as more opposite partners).

Even in West Africa, the practice of scarring, where it was most prevalent, has now almost disappeared. And it is not Christian missionaries and government bans that have played the most significant role in this, but the cities. Those who wear tribal scars are ridiculed, given hurtful nicknames like “torn face” or “ostracized”.

Nowadays, ritual scarring in Africa is no longer much in practice. Fear of AIDS, the destruction of tribal communities, and the same partner selection have destroyed a thousand-year-old tradition in just a few decades.

There are still sporadic attempts to revive it, especially in Benin and Maasai, but even the most remote communities have regularly stopped practicing ritual scarification.