Why the name of the female Pharaoh hidden for over 2000 years

Cleopatra, Isabella of Castile, Catherine the Great, and other female rulers throughout history have all made significant contributions to the advancement of civilization. These women’s names will live on in history, and their accomplishments will serve as an inspiration to future generations.

However, there were times in the ancient world when the reality of women’s reign was entirely ignored owing to the dogma that said that only a male, as a messenger of God, could assume control of the nation. Hatshepsut, the female Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, was one of these lost names.

The origin of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut was a member of Queen Yahotep’s reigning dynasty. Her grandfather, Ahmose I, was the first monarch of the New Kingdom, and her father, Thutmose I, was most likely blood-related to Amenhotep III.

Hatshepsut married her half-brother Thutmose II when she was just 20 years old. Hatshepsut was given the title “Divine wife of Amun” even as a child. During the New Kingdom, she permitted noble representatives to engage in the country’s political life.

A daughter was born as a result of Thutmose II’s marriage to Hatshepsut, and the Pharaoh gained an heir from a concubine. Thutmose III will become recognized for his superior generalship in the future, although it will be a little later. Meanwhile, Thutmose II died in the fourth year of his reign. Hatshepsut, who was the guardian of a minor prince and so gained a regency, was given his authority to administer the realm.

Hatshepsut reigned as regent for seven years, but her desire for complete authority caused her to modify the regulations, and she became Egypt’s only lawful monarch in 1490 BC. The priests were able to bend their heads without hesitation before the new Pharaoh because of their impeccable pedigree, connections, and power. For over two decades, the female Pharaoh sat on the throne. She died of bone cancer while she was in her fifties.

Thutmose III did not get an opportunity to sit on the throne since the authority was handed down via the maternal line in the 18th dynasty. Thutmose was able to take the throne thanks to Hatshepsut’s advice, who married her daughter to him.

Queen Hatshepsut’s achievements during her reign

In ancient Egypt, the rule of a female pharaoh was not nonsense, but it always aroused doubts from the populace and posed a difficulty for her colleagues. The legitimacy of a woman as a king has long been a contentious issue. Merneith, Sobekneferu, Twosret, and other queens had to show their title to the throne before Hatshepsut. Art has always served as a means of communication between the government and the general public.

Hatshepsut was well aware of the importance of art in Egyptian society, and as a result, a large number of architectural monuments were created during her reign. She also issued directives for the repair of the devastated sights. Hatshepsut was only erected by Ramses II. Hatshepsut’s reign was one of Egypt’s most prosperous periods, both socially and politically. The female Pharaoh was so powerful and daring that she participated in one of the military expeditions herself.

Hatshepsut surrounded herself with the capital’s elite, an army, and a small group of secluded priests. She established a bureaucratic structure that yielded fruit in the shape of multiple triumphs, improved Egyptian living standards, and public opinion.

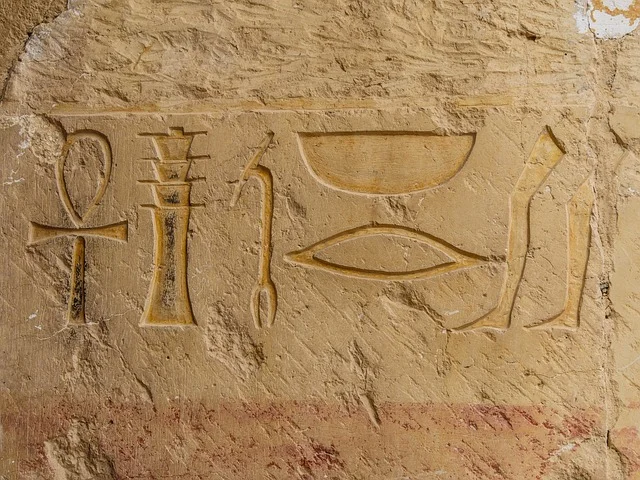

Her knowledge shone through in every aspect of her life. As a precaution against postmortem oblivion, the queen had her name carved into structures as they were being built. Every effort by later pharaohs to erase Hatshepsut’s name from history failed.

Hatred, anathema, and sons

Thutmose followed his predecessor’s commands during the first twenty years of his rule. Most of Hatshepsut’s comrades-in-arms kept their places and may even pass them down through the generations. The new king most likely realized that the Pharaoh was not only created Pharaoh by the nemes, but also by the surroundings. Then came a drive to replace Hatshepsut’s name on monuments and statues with the names of her forefathers.

Thutmose ordered the rewriting of the records, which credited all of Hatshepsut’s deeds to him. Despite the fact that her name was forbidden, the Temple constructed in her honor remained a vital cult center.

Modern historians have proposed many explanations as to why the successor chose to delete Hatshepsut’s name from history. According to experts, the most probable cause is a breach of Egypt’s thousand-year-old customs, rather than animosity.

In addition to direct leadership over the land, Pharaoh’s purpose was to restore divine equilibrium on the planet. This equilibrium is disrupted when a woman takes the place of a male. Thutmose III was probably cautious of other women following Hatshepsut’s route to the throne.

Because of Thutmose III’s active role, this woman-pharaoh was not mentioned in the Egyptian records. Orientalist Jean-François Champollion presented Hatshepsut’s personality to the world and history at the turn of the nineteenth century.

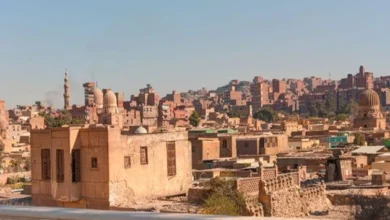

Hatshepsut’s Temple Complex

Hatshepsut’s Temple is one of contemporary Egypt’s most famous sites. At the foot of the Deir el-Bari cliffs, the magnificent building stands. The shrine was formerly known as “Jeser Jeseru,” which means “Holy of Holies.”

The building of this, of certainly, the significant object took place between 1482 and 1473 BC. Against the backdrop of the magnificent bulky structures of the period, the aerial Temple with its numerous sculptures stood out strongly.

It’s worth mentioning that the Hatshepsut Temple’s site was picked after great consideration. It was built on the axis of Karnak’s Temple of Amun, not far from Hatshepsut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings on the other side of the mountain. Senenmut, a prominent Egyptian architect and statesman of the New Kingdom’s Eighteenth Dynasty, was the Temple’s chief architect.

The Hatshepsut Temple, formerly a garden complex with exotic plants and lakes, today sits almost in the midst of the desert. The murals on the walls portray events from Hatshepsut’s reign, as well as scenes from ordinary life and the gods.

Hatshepsut’s Temple evolved into a true pilgrimage site throughout time. On its walls, archaeologists discovered several inscriptions and letters requesting healing.

The Temple held a Coptic church in early Christian times, but it was eventually demolished. Egyptologist Edward Naville was the first scientist to reconstruct the Temple in 1891. Because many of the structure’s pieces were removed from Egypt, this endeavor was incredibly challenging. The Temple was repaired, and Hatshepsut’s legacy was restored, owing to the work of Polish restorers.

Perhaps this history’s calling: to bring back from the depths of memory what has been forgotten, lost, or obliterated by generations. And only history can reveal what is known about Ancient Egypt’s final monarch.