Why is genital mutilation continuing to affect women in Africa? A mixture of “tradition”, but also “business”.

More than 91.5 million women over the age of 9 live with the aftermath of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Africa. And three million girls are likely to suffer each year. The countries with the highest prevalence of FGM among women aged 15-49 are Somalia (98%), Guinea (97%), Djibouti (93%) and Mali (91%). Overall, the numbers show a regression but the practice remains rooted. In some countries, such as Uganda, authorities have noted a resurgence of FGM, which has been banned since 2010. Why does the phenomenon not run out of steam?

Limited approach to fighting female genital mutilation

NGOs are engaged in the fight against this custom. Their actions are certainly beneficial but seem to have some shortcomings. Sensitizing agents are generally unknown in communities practicing mutilations, hence the mistrust of the populations; their messages are unlikely to win their support. Most of the time, they revolve around the harmful consequences of these mutilations. Yet these communities have a very different perception. For example, the death of a victim can be interpreted as the wrath of a genius. In addition, the communication channels used are not always the most suitable. Financial support for circumcisers willing to drop the knife, and the protection afforded to girls who refuse to be mutilated, remains weak.

Because of limited budgets, NGO actions are ad hoc and do not have a long-term impact on the long-term. During the sensitization sessions, several excisors report abandoning their practice. But once they look away, they take back the knife. Laws penalizing FGM, on the one hand, do not take into account the opinion of the communities that practice them, and on the other hand, are not sufficiently popularized within these communities often living according to traditional and cultural norms on the fringe formal laws. This is why these actions are often perceived as hostile to local culture.

Mutilation sources of income and social status

FGM is sometimes seen as a prerequisite for marriage: a dual way of keeping oneself pure until one and then remaining faithful to one’s husband. Girls who do not join are considered dirty, frivolous and unworthy to be married. They are therefore marginalized. On the other hand, excisors enjoy certain privileges in their communities and are considered custodians of tradition and their word is taken into account.

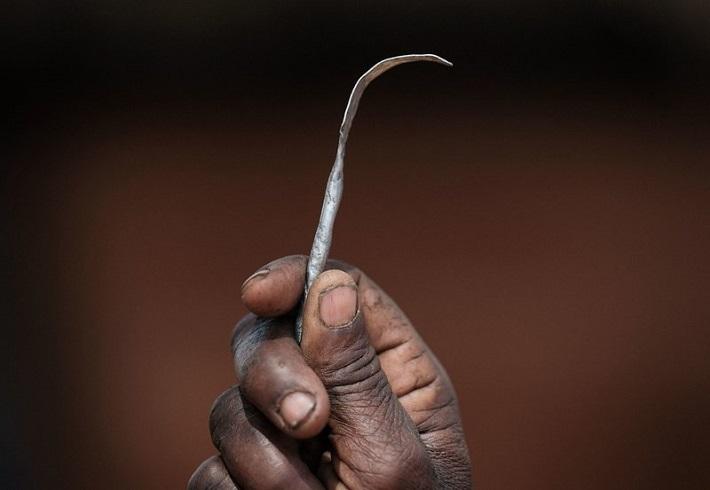

As a result, they receive various gifts in kind and in cash. FGM is, therefore, a source of income. For example, Oumou Ly, a former Malian circumciser maimed 40 girls each Monday and as much on Thursday and earned between 200 and 300 thousand CFA(ranging from 3-4 USD) francs per week, or 7 times the Smic (40 000 CFA francs (almost $70)) in Mali. The benefit of an adult woman cost 10,000 CFA francs (almost 16 USD). Therefore, FGM constitutes a business very lucrative, leading circumcisers to professionalize and export themselves even across borders.

Moreover, they can also sell the severed female organs and the blood of the victims to the fetishes and marabouts who use them for mystical purposes: to strengthen the power, to prosper in business, to obtain a professional promotion, success and spiritual protection against its enemies… politicians, businessmen, senior officials and workers, athletes, and many others, use the services of these fetishes and marabouts. Thus, it is a whole economic ecosystem that develops around FGM, each and everyone doing everything to preserve their privileges and benefits, thus creating a real resistance to change.

Which alternative strategy?

The fight against FGM requires a more systemic and participatory strategy with contextualized solutions. Thus, people from these communities should be more involved in actions for collective awareness. This would be beneficial to deconstruct the cultural myth of FGM and disconnect it from marriage for example. To achieve this, communities should break the taboo on sexuality and give their children good sex education instead of using mutilation to deter them from unbridled sexuality. In this sense, excision/genital mutilation ceremonies should be replaced by rites in which girls receive education about sexuality and the management of the home.

The excisors could be converted into sex educators and have the burden of rituals replacing the mutilations in return for remuneration. The latter will have to be reinforced by other sources of income through training programs and financial support for gainful activities. Community media could be of great help in raising awareness of the abandonment of FGM through messages in local languages. They could also promote girls’ sex education rites so that they fit into the culture. The new generations will have to be a privileged target, their rejection of FGM can be an asset to achieve an end to this custom.

Awareness

To do this, the actors of the civil society would be privileged channels in the diffusion of this message. Measures must be taken to prohibit the use of parts and human blood by marabouts, witch doctors and other mystics. Awareness could be implemented before a severe crackdown. Finally, in order to obtain popular support and strengthen respect for the law, this awareness campaign should be developed in consultation with local communities.

The fight against female genital mutilation is a long struggle that can not be won without taking into account cultural resistance, but also economic issues related to such practices. Sporadic awareness campaigns or laws that are as repressive as these will only be effective if they meet with popular support and involvement. Hence the need for a more comprehensive and adapted approach that emanates from the local context.