One of the most exciting nuances in archaeology is that it is an ever-changing science, forcing people to revise their previously seemingly cool ideas about the past and the people who inhabited the world before. Scientists often make awe-inspiring discoveries that will forever change the understanding of civilization.

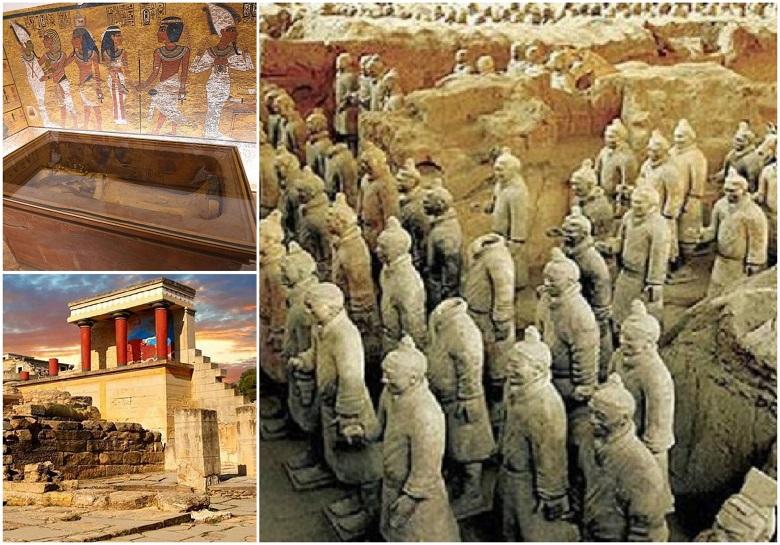

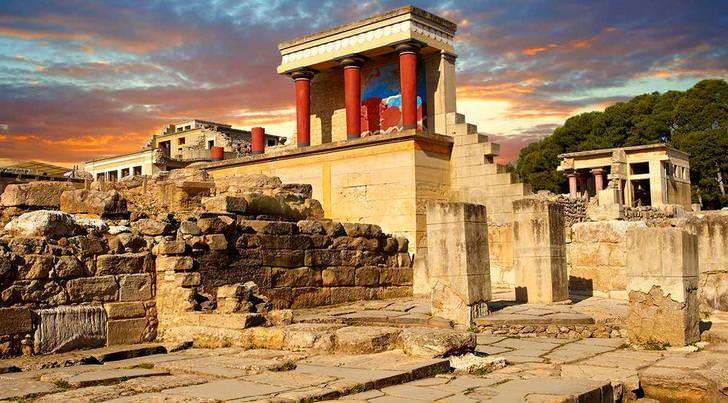

Knossos, Crete

Arthur Evans 1900-1905 During excavations, he discovered a vast palace complex of the Middle Bronze Age (circa 1900-1450 BC), numbering about 1300 rooms, many of which were decorated with colorful frescoes, dolphins, griffins, and athletes jumping over bulls.

The most important discovery, however, was the thousands of baked clay tablets. These tablets bore inscriptions in a never-before-seen language called Linear B. No one could read the ancient records, and it was only 50 years later that Michael Ventris could decipher them.

Tomb of Tutankhamun, Egypt

Perhaps one of the most famous (and impressive) archaeological discoveries of all time was Howard Carter’s excavation in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. Thanks to him, the reigning and, perhaps, politically not very important pharaoh got into the history books for a short time.

Tutankhamun died in adolescence, but his grave was literally “filled” with beautiful objects corresponding to his royal status. And, what is most striking and unusual, it was not plundered.

Machu Picchu, Peru

The lost city of Incas, which Hiram Bingham rediscovered in 1911, was built in the middle of the 15th century on the top of a mountain. The stunning natural surroundings and impressive remains make this place a vivid reminder of the technological capabilities and power of the Inca Empire at its height. Terraced platforms and cave cemeteries have provided a fascinating insight into the lives of about 1,000 people who once lived here.

Sutton Hoo, England

Finding a stunning mound cemetery in the UK was thanks to the curious lover of spiritualism, Edith Mary Pretty. During the excavation of a group of low grassy mounds in Suffolk, something unique was discovered: a huge funerary boat with a rich “catch” of Anglo-Saxon artifacts, including imported Byzantine objects, mysterious religious symbols, items for recreation and leisure, and weapons. They provided a vivid view of the Anglo-Saxon world. \

Rosetta Stone, Egypt

This find gave the key to the modern understanding of hieroglyphs more than 1000 years after knowing how to read ancient Egyptian symbols was utterly lost. Discovered by Napoleon’s army during the fort’s construction, this stone slab contained inscriptions in three languages: Greek, demotic, and hieroglyphics. Thanks to the Greek translation, the French school teacher Jean-François Champollion published the complete translation in 1822.

Tomb of the first emperor, China

Around 8,000 terracotta soldiers stand in orderly ranks to protect the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, who unified China and became its first emperor. They are accompanied by 130 chariots drawn by over 500 horses, 150 cavalrymen, civil officials, acrobats, and musicians. Discovered by farmers in 1974, the burial ground in which they are located is a World Heritage Site. It is simply a great symbol of the power and creativity of the rulers of ancient China.

Akrotiri, Greece

While this remarkably well-preserved Bronze Age city on the Greek island of Santorini is not as well known as the Roman ruins in Pompeii, it provides an equally vivid insight into the lives of its inhabitants. Recently opened to the public, Akrotiri was once a thriving shopping centre, abandoned after a volcanic eruption buried the city under a layer of ash. Many two- and three-story houses in the town survived, along with furniture and pottery, remaining intact for 3,500 years until Spyridon Marianatos excavated the site in 1967.