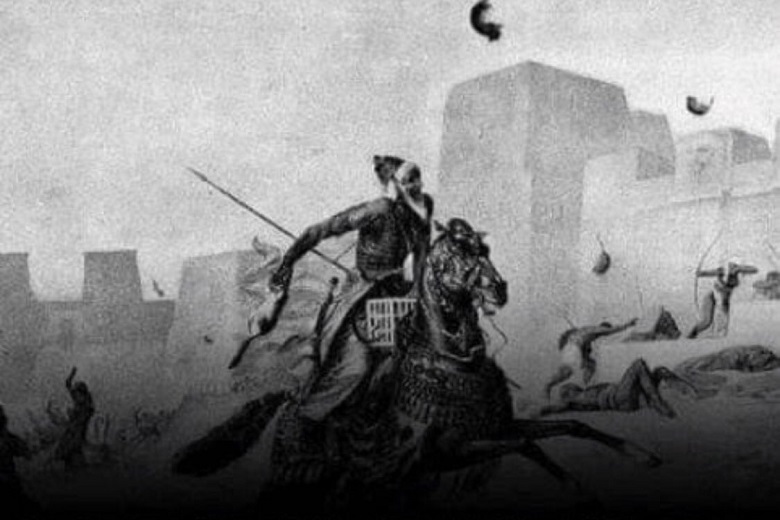

Throughout history, it has not been enough for people to kill each other in their endless wars. They have also destroyed innocent animals. In the Legendary Battle of Pelusium, the Persians defeated Egyptians by throwing innocent Cats on them.

Traditionally, it was riding animals such as horses, mules, and elephants that suffered. Less often, dogs, birds, pigs, and snakes. Different kinds of them were used in different ways. Probably one of the most unheard-of aids to warfare were…cats! It was the whiskers and stripes that helped the Persians defeat the Egyptians. Below are the details of the most unusual battle involving the world’s first psychic attack.

It’s pretty hard to imagine a fighter like Vaska. Cats are not big or formidable animals. Not lions! Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II, for example, had a trained lion. He fought at his side at the Battle of Kadesh. There are similar cases with tigers or leopards. Here a cat is unlikely to have the strength to stand up to a warrior. However, history knows at least one case in which this species was responsible for taking a city: the battle of Pelusium.

Pelusium was a major city in Lower Egypt, located in the Nile Delta. However, the name came from Greek and was given to the city later. Its real name was Per Amun. By the middle of the 6th century B.C., little remained of the ancient Egyptian splendor. At that time, the Pharaoh of Egypt did not have enough power to resist the expansion of the Persians. The historian Herodotus tells the extraordinary story of the fall of Pelusium. The Egyptians were actually defeated…by cats.

The weakening of Egyptians

In 526 B.C. Psammetichus III, son of Amasis II of the XXVI dynasty, ascended the throne. The period of the latter’s reign was successful and long, more than forty years, indicating that he was a good ruler. After all, he did not belong to the royal family but came to power due to a military coup. Egypt’s influence under Amasis was great and stretched to all sides of the world. But another powerful and ambitious empire, the Persian Empire, was already emerging in the east.

The historian Herodotus describes a curious reason that served as a trigger for all subsequent events. Amasis sent his physician to the court of the Persian king Cambyses II. Egyptian physicians at that time enjoyed great fame and respect throughout the world.

The doctor did not want to go there and was indignant at being sent to Persia against his will. He decided to take revenge by sowing enmity between the rulers. The doctor suggested to his new master that he ask Pharaoh for his daughter’s hand, knowing that this proposal would not please him very much. Amasis responded by sending the king the daughter of his deposed predecessor as his own, but she revealed the truth to Cambyses. The Persian king felt very much insulted.

Diplomatic relations between the countries were hopelessly ruined. Among other things, at the court of Amasis, Pharaoh’s adviser, a Greek mercenary named Phanes of Halicarnassus, fell out of favor. He began to seek refuge in Persia after a disagreement with the Pharaoh.

It was Phanes who convinced Cambyses that there would be no better moment to conquer Egypt. Of course, there were deeper reasons for this – economic and political. During the reign of Psammetichus III, son of Amasis, a disaster struck.

The young and inexperienced Pharaoh could not even be compared with the powerful figure of Cambyses II, the heir to Cyrus the Great, ambitious and warlike. Egypt was already the only state that remained independent from the Persians in this region, so its conquest was only a matter of time.

In 525 BC., the Persian army launched an offensive and crossed the Sinai Peninsula. The only way for the Pharaoh to save the country was to get help from Greece. With the Greeks, he maintained good trade relations, but it turned out that they joined Cambyses with their entire fleet. Egypt’s fate was sealed.

Fate of Pelusium.

Psammetichus personally led his army to try to stop the advance of the enemy. Pelusium became the scene of a clash. The number of troops on both sides is unknown. In his writings, the Greek historian Ctesias wrote that both the Egyptians and Persians had foreign allies and mercenaries. The battle was bloody, and the outcome was a foregone conclusion. At the time, the Achaemenid Empire was the major power of the ancient world. Egypt was not a rival militarily.

The Persian armies devastated the Egyptian formations, who showed terrible confusion when they saw that the enemy wore the image of Bastet on their shields. Depicted as a cat, or a woman with a cat’s head, at various times, Bastet was revered as the goddess of fertility, love, merriment, hearth, and childbearing.

She was considered the all-seeing eye of the great Ra and his faithful companion in the fight against Apop. According to another version, they were not painted images but real live cats. The Persians used them as shields, from which they simply dropped their weapons, accepting defeat.

Herodotus gloomily describes the piles of Egyptian skulls. Ctesias tells in greater detail that the Persians killed fifty thousand Egyptians against seven thousand of their soldiers. Unable to withstand the onslaught of the enemy, Psammetichus and the survivors had to retreat and take refuge behind the walls of Pelusium dramatically.

The Egyptians were ready for a long siege. But there was no need for this. Thanks again to the cats. The Macedonian commander Polieno in the 2nd century A.D. wrote a military treatise in eight books called “Stratagems” (of which only references remained because they were lost).

There he talked about how the Persians threw cats at the Egyptians. High inaccessible battlements were supposed to protect the besieged from the enemy. When sacred animals flew through the walls, the goddess Bastet’s incarnations completely paralyzed the Egyptians and forced them to leave the fortress. They continued to flee and went on to Memphis.

Fall of Memphis

Herodotus wrote nothing about this. He mentions another, no less demoralizing story. Cambyses desecrated the tomb of Amasis and burned his mummy. Then, after capturing Pelusium, he sent a messenger to Memphis to negotiate a surrender, but the Egyptians killed him.

After that, the real revenge began. For every Persian killed, ten Egyptians died. Some were killed in battle, some were executed later. More than 2,000 of Memphis’ elite were executed, all the top military and high-ranking officials, even one of the Pharaoh’s sons.

Memphis fell. Psammetichus was taken prisoner and subjected to humiliation. His daughter was forced to carry water from the Nile for the Persian horses, and his son was chained and harnessed like an animal before he died. After all this, Herodotus describes a supremely fascinating epilogue. He tells of how a Persian army was sent to capture the oasis of Siva.

There was the famous oracle of Amon, the same one that Alexander the Great later visited to become ruler of the world. The place is inland, in the middle of the desert. The soldiers of Cambyses were caught in a terrible sandstorm and remained there forever. This is probably a legend, typical, but so fascinating that many have tried to find evidence of it. In 2009, an Italian archaeological expedition did find human bones there, along with weapons and bronze jewelry. The remains were identified as Achaemenid.