Kenyans marathon runners: the secret exposed!

Kenyans dominate the top of the marathon. Is it a matter of training or genes, or is there something pushing them faster?

Like a group of gazelles in the African savannah, they dart gracefully across the asphalt of Rotterdam tomorrow. With a giant, smooth stride from their long, thin legs, not a trace of fatigue on their faces. And that for 42 kilometers and 195 meters.

You can set the clock on it: a little afternoon, an African will be the first to pass the Rotterdam Marathon line. Chances are it is a Kenyan. Take the year 2018 top 10: seven Kenyans, two Ethiopians, and a Belgian of Somali descent.

The Kenyans’ supremacy in the marathon is unprecedented. Only the Ethiopians can sometimes follow their trail, followed by some lost Somalis, Eritreans, and Tanzanians. The stock of top Kenyan runners seems to be inexhaustible. In recent years they have won the vast majority of medals in the (medium) long-distance world championships and Olympic Games.

Scientists

There is no hard evidence, but scientists have theories that can explain why Kenyan runners are ahead of Western runners. It is a combination of favorable cultural, socio-economic, and genetic factors.

“It always looks great,” says Jaap van Dieën, professor of biomechanics at the VU University in Amsterdam. “Western runners can also have good running technique. That’s not the difference. Instead, this is due to Kenyans’ physique, limited economic alternatives, and the tough mutual competition. Running is the sport in Kenya.”

Hunters

Little consolation: not every Kenyan can complete a marathon in just over 2 hours. Most top runners come from one specific tribe, the Kalenjin. They are only five million, about a tenth of the Kenyan population, but three-quarters of the elite runners are from this tribe.

Kenyans have been used to walking since childhood. They are initially hunters. A young Kalenjin earns “adult” status after running to catch an antelope. “Their progress is also partly due to the circumstances,” says Van Dieën. “They live and train at altitude. As a result, their body makes more red blood cells, which improves the oxygen transport from the lungs to the muscles. These also benefit the performance in lower altitude.”

Moreover, thanks to the prize money at international marathons, running is a way to escape poverty. That’s why the competition is fierce and only the very best come out.

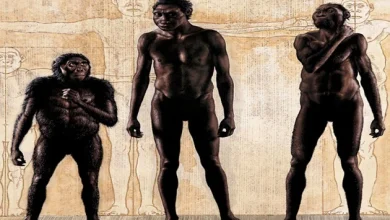

But the success of the Kenyans is also in their genes. They are slender build, have skinny legs, narrow ankles, and calves, but strong tendons and strong muscles sit in a favorable position. Van Dieën: “It is helpful if your muscle mass is high in your legs. Then you have to swing less mass back and forth. You also benefit if the muscle part of your calf is short and the Achilles tendon long.”

The elastic Achilles tendon absorbs energy when the foot lands on the ground so that the runner has to generate less energy himself. “The Achilles tendon works like a spring,” explains Van Dieën. “If you land your foot on the ground while walking, the calf muscle and Achilles tendon are stretched and rereleased at the take-off. If the tendon is longer, more energy is stored on landing and then reused during take-off. Then you walk more efficiently. You can use the energy you save to make speed.”

The function of the lung system is also essential. The lungs’ ability to take in oxygen and the muscles’ capacity to carry oxygen from the blood are genetically determined.

The latter also applies to the type of muscle fiber. Sprinters have fast, powerful fibers (‘fast twitch’) for a short, explosive effort, and endurance runners have slow, fatigue-resistant fibers (‘slow twitch’) for long-lasting exercise.

How enzymes in the fibers release energy determines the speed at which the muscles contract (contract). African marathon runners have ‘slow fibers,’ which give the muscles better endurance and less acidity. Van Dieën: “A key factor in marathon running is not only that you can run fast, but that you save energy and can keep it up for two hours.”

Thin limbs

Other researchers cite the African advantage of thin, long limbs. Due to a larger skin surface, heat can be more easily separated from the body and takes less energy to cool.

In short, many African top runners have a ‘good design,’ according to Van Dieën. Logically, the Kenyans on the sprint numbers are not to see in any fields or roads. Sprinting requires a heavier physique. Muscle strength is more important there than efficiency. That’s why Usain Bolt looks different from Haile Gebrselassie.

Head Start

Does it then remain hopeless for the non-Western marathon runners? Van Dieën doesn’t think so. At least for now. “It is not an impossible difference. There are also trainable factors. You cannot change much in terms of training in the construction of your leg. That is a matter of disposition. But it is not sure whether the Kenyans have a head start.”

Kenya has a larger running population with tough competition. They train very hard. It means that many runners drop out or stay at the top for a relatively short time and that those with the most talent remain.

“In Western Europe, you also have talented people, but there is not a broad base here like in Kenya. People only start running when they are too old. You should make running just as popular here as in Kenya. If we are still behind the Kenyans in twenty years, we may conclude that the difference is impossible cautiously.”