Nowadays, few people can envision a world without refrigerators, freezers, or ice machines. Ice is a necessary part of our everyday life since it allows us to chill and preserve food as well as enjoy a variety of cold treats.

Ice has been a commodity since the early twentieth century, but most people are unaware that the prevalence of ice in our lives is due to the pioneers of the ice trade’s lengthy and difficult fight in the nineteenth century.

The ice trade began in the early part of the nineteenth century, with Frederic Tudor, a Boston industrialist known as the “Ice King,” as its most famous pioneer. Tudor was not connected to the renowned English Tudor royal family, although his elder brother, William Tudor, was a notable early 19th-century literary personality.

When Frederic Tudor was a youngster in the 1790s, ice was a luxury item reserved for America’s upper crust. During the winter, the rich paid local workers to use axes and saws to carve ice into the lakes. The ice was then kept in deep enclosed wells and utilized by the rich to create cocktails and other beverages for their visitors throughout the summer.

Tudor became aware of this activity and thought that ice might be marketed and sold to the general public across the nation.

In the late 1790s, he traveled to the Caribbean and discovered that the natives urgently needed ice to preserve fish and meat. Tudor decided to start exporting ice from Massachusetts to the Caribbean since Massachusetts has numerous lakes that freeze in the winter. When he was 23 years old, he purchased his first ship, the Favorite, a medium-sized brig.

In February 1806, he made his first ice shipment from Charlestown to Martinique. The people in Massachusetts were very dubious of his attempts, and the press openly mocked his new venture: “No kidding. In Martinique, the ship passed customs with a cargo of ice. We’re hoping it doesn’t turn out to be a risky endeavor.”

His ship had approximately 80 tons of ice on board, and nearly half of it melted on the way to Martinique. Despite this, he soon sold all of the leftover ice to the locals, earning approximately $4,500 (about $85,000 in today’s money). However, the funds were insufficient for the trip, and he started to experience severe financial difficulties.

Despite his growing debts, the Ice King started shipping massive amounts of ice to Martinique and Cuba. He was sure that the business would become successful after establishing regular routes and figuring out how to keep ice from melting in the ship’s cargo hold since the ice was free and only employees had to be paid. Between 1806 and 1816, his debts ballooned to the point that he was forced to spend several months in debtors’ jail.

His struggle, however, eventually paid off in 1816. He developed a regular route to Cuba and was able to purchase many additional ships as a result of his efforts. He also pioneered a novel technique for transporting ice: he insulated the ice with sawdust and hay, and only approximately 10% of the ice melted throughout the three-week journey. He started promoting ice supply in the United States and the Caribbean, and the ice industry grew rapidly.

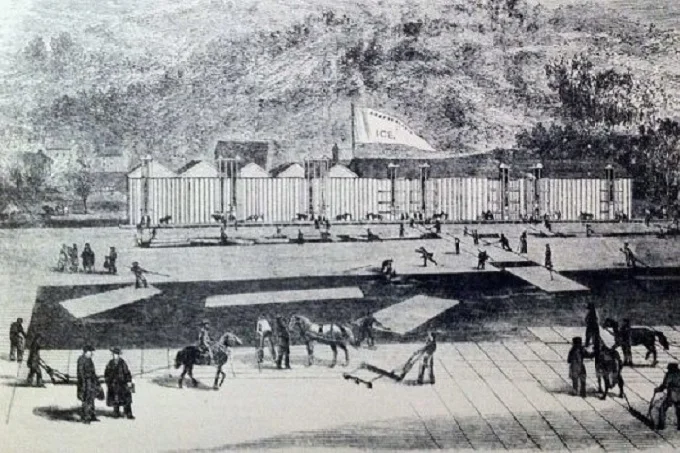

Tudor was a multimillionaire by the late 1820s. Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth, an explorer, and inventor, developed horse-drawn ice saws that were very effective in cutting ice. Tudor collaborated with a Boston trader called Samuel Austin and started exporting ice to Kolkata, earning him the title of “Ice King.”

Tudor’s ships were highly prepared and could transport up to 180 tons of ice, despite Kolkata being 16,000 miles and four months distant from Massachusetts. Over the following 15 years, he constructed three massive ice warehouses around Kolkata, earning $220,000.

His company failed in the 1850s when numerous businesses across the globe started selling ice, and it was found that ice could be readily manufactured using steam, so there was no longer a need to carry it.

Furthermore, the refrigerators, the distant forerunners of the contemporary refrigerator, were patented and eventually found their way into the homes of regular people.

On the other hand, Tudor’s last 25 years of life were years of riches, leisure, and quiet retirement. He married a lady 30 years his junior and amassed sufficient wealth to sustain many new generations of his family.