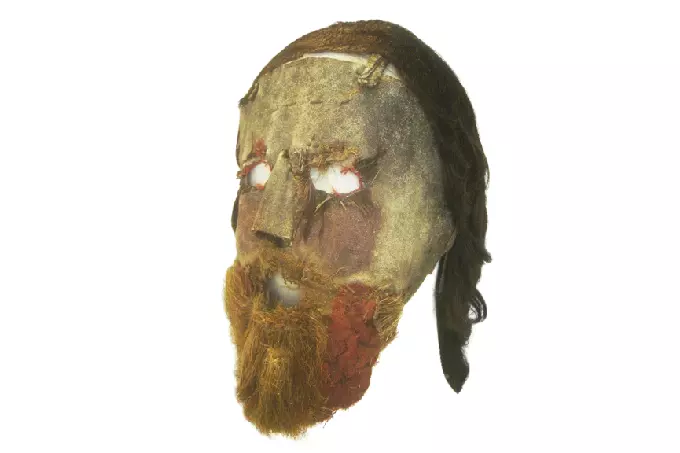

A Scottish clan inherited this mask as a sacred relic until the 19th century. However, in 1840 when the clan that kept it tragically perished (there were even rumors of the mask’s curse), the artifact became the property of Edinburg University. And, it must be said, this patrimony is quite creepy.

The mask is made of leather (fortunately not human) and cloth. It is framed by a red mop of human hair, with false wooden teeth in the mouth and bird feathers around the eyes. All this makes the mask devilishly sinister. It would have looked great in a horror movie about occultists, but it belonged to a man revered as a saint. His name was Alexander Peden, and he was Scottish to the core. Fiery and fanatical, unstoppable as a battering ram, yet full of black melancholy, he was the near-perfect prophet.

He was born in 1626, in a dark age for Scotland and England. The Civil War, the Religious Reformation, the execution of the king, and the reign of Cromwell. The young clergyman, trained at the University of Edinburgh, had much to talk about with his rebellious flock. And he was unstoppable. All his life Alexander Peden had preached – zealously and exuberantly, driving himself to frenzy and the crowd to ecstasy with his speeches.

He would rather be called a dark visionary than a priest. Preaching Presbyterian doctrines, he went “into the fields”. Settling in a cave, Peden roamed the neighborhood, gathering crowds of peasants. At first, they surrounded him to make fun of the fool, then they fell under his influence and listened, roaring with ecstasy.

Peden quickly rose to fame as a prophet and could have started a revolt against the English crown or founded a cult of his own – there were plenty of admirers. But he preferred to remain an itinerant oracle and preacher of the fields. However, the English, who had barely restored the monarchy, expectedly feared every suspicious Celt.

Alexander Peden was hunted down. So he moved around the country exclusively at night. And to prevent the soldiers from recognizing him, he created this mask. Though when you look at it, you’d rather believe he was scaring them to death. It’s hard to imagine anyone wearing it pretending to be a real person. But a wandering spirit, a boggle, is.

The predictions Peden gave were hazy and obscure, like a pagan oracle, but all, as one, came true. Because that is how the memory of the crowd works-they were ready to believe that the vague words of the holy madman contained a prophecy, and they readily sought it out.

Once the prophet did get pinned down, not even the ghastly mask helped, and in 1670 he fled to Ireland. There he continued to preach, but he was treated with apprehension. The Irish were alien to the Scottish frenzy of Presbyterianism, so three years later, he returned home, where he was captured and sent for four years to Bass Rock Island Prison, which resembled either Alcatraz or Azkaban.

Peden served his time with similarly assembled charismatic prophets from all over the country, so it was probably the craziest bunch that could ever be assembled in one building. He came out even more fierce, but cautious. The mask was returned to him by his followers so that he did not part with it until his death.

He lived until 1686, wandering and prophesying. It is said that after prison, he became insane and began to preach directly in his creepy mask, which had already become part of his personality. Peden ceased to entice the crowds, his speeches became too frightening and too redolent, and his old followers preferred to forget about him.

His only apparent prophecy was of the utmost grimness. In 1682 Peden officiated at the marriage of farmer John Brown and Isabel Weir but overshadowed it with the words addressed to the bride: “You have a fine husband, but your happiness is short-lived. Keep a linen cloth ready – it will come in handy as a shroud for him. The exodus will come when you don’t expect it, and it will be bloody.”

In 1685, just three years after the wedding, English dragoons surrounded the Brown farm and shot her husband for disobeying the authorities – he refused to accept Anglicanism and recognize the king as head of the church.

After his death, Alexander Peden found no resting place: forty days after his burial, British soldiers exhumed the body and moved it to another place. This was done deliberately – so that the grave would not become a place of pilgrimage. So, according to Scottish beliefs, Peden really should have been a boggle – a malevolent spirit who roamed the roads and drove lonely travelers mad. And looking at his mask, it’s easy to imagine what he’d look like in his new form.