The Pintupi Nine or the Lost Tribe: mysterious people of Australia

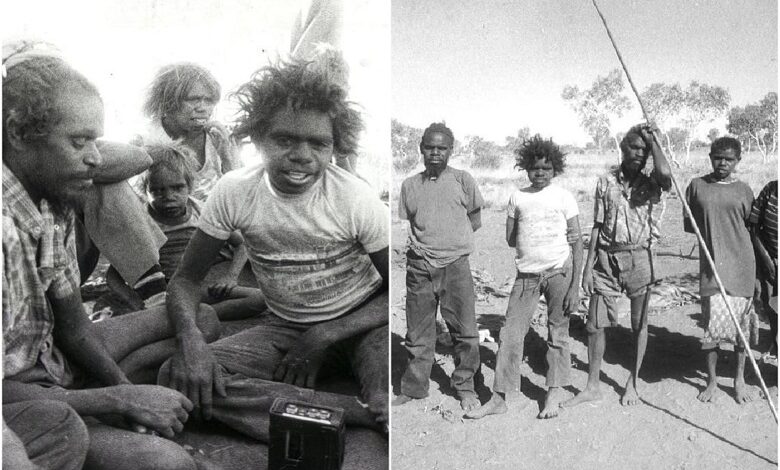

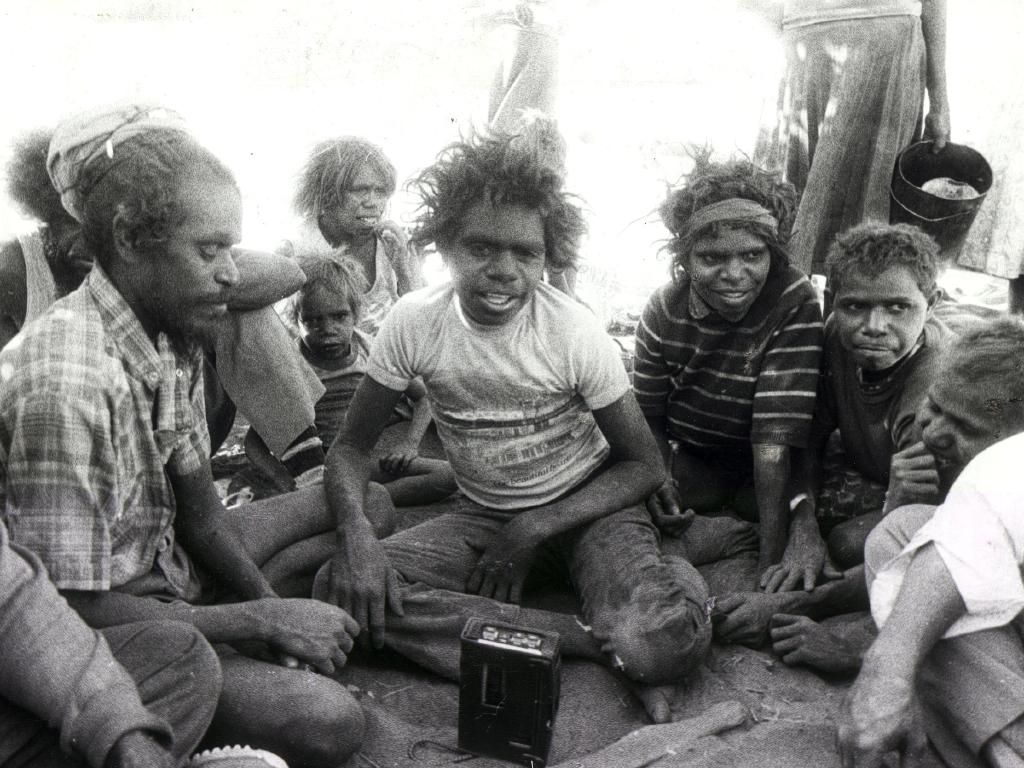

The Nine Pintupis were a group of nine people of the Pintupi tribe who lived in a traditional hunting-gatherer desert manner in the Gibson Desert in Australia until 1984 when they came into contact with their relatives near Kiwirkurra.

They are sometimes also called the “Lost Tribe.” The group was hailed as “the last nomads” in the international press when they left their nomadic life in October 1984.

History of the Lost Tribe of Australia

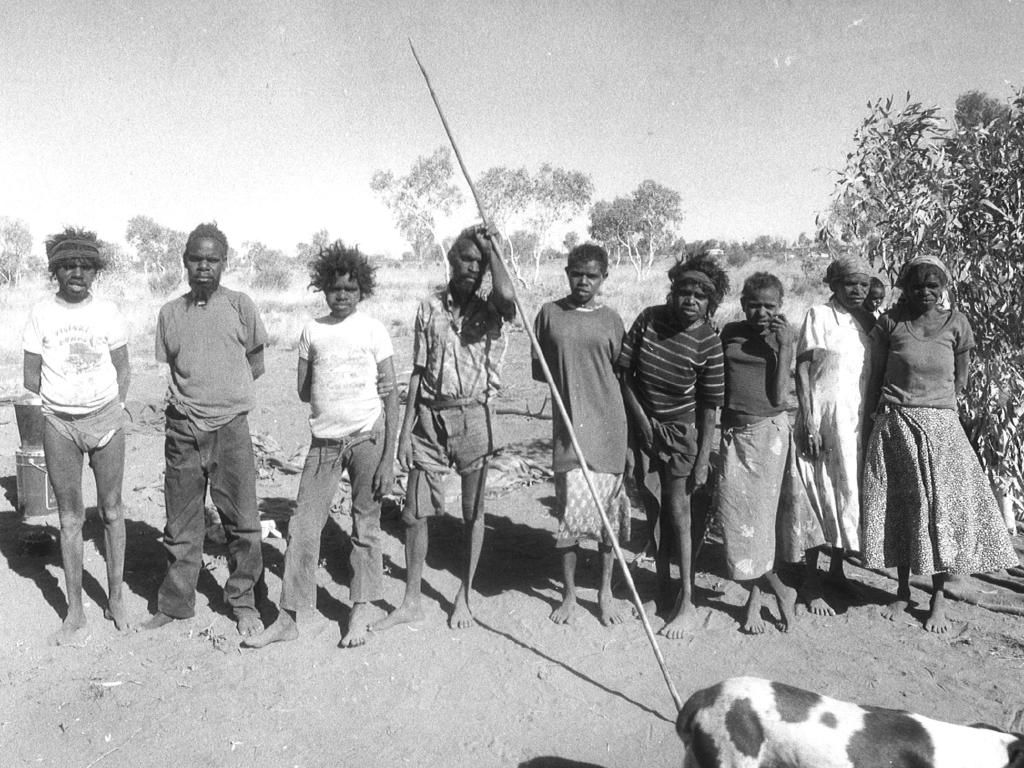

The group roamed between water wells near Lake MacKay, near the Western Australia-Northern Territory border, wearing hair-cloth belts and armed with two-meter wooden spears and woomera throwing spears, as well as intricately carved boomerangs. Their diet dominate by monitor lizards and rabbits, as well as native bush food plants.

The group was a family of two co-wives (Nanyanu and Papalanyanu) and seven children. There were four brothers (Warlimpirrnga, Walala, Tamlik and Piyiti) and three sisters (Yalti, Yikultji and Takariya). The boys and girls were in their early or late teens, although their exact ages not know; mothers were under 40 years old.

The father of the family – the husband of both wives – died, possibly from poisoning from tainted canned food found in an old mining camp. After that, the group went south, to the place of their alleged residence of their relatives, as they saw a “haze” in that direction.

They encountered a man from Kiwirrkura, but they again retreated to the north due to a mutual misunderstanding. In contrast, he returned to the community and warned the others, who then went back with him searching for the group. Community members quickly realized that the group was relatives who had been abandoned in the wilderness twenty years earlier when many of them had hiked closer to Alice Springs.

The community members traveled by car to the point of contact and then tracked them down for a while before finding them. After establishing connections and clarifying their relationship, the Nine Pintupi invited them to move to Kiwirrkura, where most of them still dwell today.

The Pintupi-speaking trackers told them that much food and water had come out of the pipes; Yalti said the concept amazed them.

A medical examination revealed that the Tjapaljarri clan (by whose name they also know) was “in excellent condition. Not an ounce of fat, a well-formed, strong, fit, healthy breed. At Kiwirrkura, near Kintore, they met with other members of their sprawling family.

In 1986 Piyiti returned to the desert. Warlimpirrnga, Walala, and Tamlik (now known as “Thomas”) received international acclaim in the art world as the Tjapaltjarri brothers… The three sisters, Yalti, Yikultji, and Takariya, are renowned Aboriginal artists whose work can be seen at the exhibition and purchased from several art dealers. One of the mothers died; the other settled with three sisters in Kiwirrkurra.

The Lost Tribe is a sensation of discovery

The group’s discovery caused a media sensation, but the headlines referring to the “lost tribe” annoyed them – they were not lost, they insist, segregated from their family members and other people of the Pintupi clan.

The nine consisted of two sisters and their seven children – teenagers – four brothers and three sisters who had one father. How did they become so isolated?

In the 1950s, the British began testing Blue Stripe missiles over the Western Desert, and the Australian government decided to “surround” the desert nomads and relocate them to settlements.

All the Pintupi’s take away except this family, which went unnoticed. Since then, suddenly alone in the desert, they saw very few signs of anyone’s existence.

Yukultji remembers seeing planes when she was very young. The plane will fly by, and we will hide in a tree. We saw the wings of the plane and were scared. We assumed it was the devil, and so we held on.

New life

Once again, the establishment of the settlement brought Pintupi closer to a family that remained lonely for up to 20 years. Those who most closely related with the Nine Pintupi often spoke of family members who were still “in the bush” and left out – they always wondered what happened to them.

Warlimpirrnga, the elder brother and head of the family after his father’s death, recalls the day the family bumped into other clan members.

“We just pierced a kangaroo with a spear. We could smell other people’s feces in the air — they were probably a couple of kilometers away — and we saw smoke in the distance.”

“We came closer, stood on the rock, and saw below the people who set up camp. Therefore, I began to approach their base. I ran to where they stood. Then he crept closer. I coughed; people heard me. It looks like they were scared. They went mad, running back and forth,” he says.

“This is my grandfather’s land,” said Warlimpirrnga. One of the men began filling a canister with water for them. “When he did that, we thought we weren’t going to pierce him with a spear,” says Warlimpirrnga. “They were so scared. They were terrified of us, afraid to die.”

The camp inhabitants were a Pintupi, Pinta Pinta, and his son Matthew, who decided to establish an outer station at a place called Winbargo, 45 km from Kivirrkurra. The young man freaked and fired a shotgun into the air – everyone scattered to the sides, and the two men drove away at full speed, despite a flat tire.

“We heard the sound of this car from afar,” Warlimpirrng expressed.

These were the first occasion he and his brother Thomas had encountered running water, clothed people, or a car.

Pinta Pinta and Matthew rushed back to inform the rest of what they had witnessed. We know their part of the story from Charlie McMahon’s diaries, now a famous musician, but then the only Whitefella who helped 60-80 Pintupi establish a community in Kivirrkurra. He nicknames Murrahook because he had a hook instead of a hand.

The last nomads?

The Nine Pintopi may not have been the last to abandon traditional outback life – in October 1986, a nomadic band of seven reportedly emerged from the Great Victoria Desert – it is unclear how knowledgeable they were about modern society. A government report praises them for surviving “one of the harshest and most remote places in the world.”