Angola war: the story of a country at war

Today’s modern history of the Angola territory began in 1575 when some Portuguese caravels reached its coasts, full of soldiers and future new settlers.

The relations between these territories and the Portuguese had begun a few decades earlier, when the area was part of the Kingdom of Congo and was called Ngola, which, in the language of the kingdom, meant “king”.

The two rulers perceived the relationship between Portugal and its future colony as equal: in exchange for weapons, the introduction of new technological tools, and the teaching of the Christian religion, Angola provided slaves, minerals, and ivory.

The Portuguese began to have absolute and complete control of the area only after the Berlin Conference. The Conference on Africa, which started on November 15, 1884, and concluded on February 26, 1885, began the so-called race for Africa and was the scene of a meeting in which the most important European powers divided up control of the territories of the black continent.

Portugal was granted the right to control the colonies of Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe, but in order to put into practice what had been decided in theory, it was necessary to demonstrate the actual occupation of the land concerned and the Portuguese government thus took the opportunity to tighten its control over the territories that were now colonies. This turned out to be an arduous task for the small southern European state, and the actual occupation was achieved only in the 1920s of the following century.

During the period of the Portuguese domination, the area of present Angola had obtained the terrible primacy of being the major supplier of slaves, thus earning the nickname of black mother of the New World; the price of slaves was decided according to the conditions of the teeth, and the Angolans had learned to break them and to tear them off, in order to have little value and not to be bought.

Once the slave trade was abolished, the conditions of the native inhabitants of the Portuguese colony of Angola did not see any improvement: when the decolonization process began at the dawn of the 1960s, the Angolan people were poorer and less educated than those of the other European possessions in Africa, lacking in primary services and poor in infrastructure.

The white population was certainly in better conditions, given that blacks were often forced to work first on cocoa plantations and then in gold and diamond mines, but it was still one of the least “wealthy” on the continent.

Portugal was a poor state if compared to the other European powers. If, on the one hand, it did not have the economic possibility to promote the development of its colonies, on the other hand, the only way it had to show its strength and to have a voice in the decisions at the international level was to maintain its dominion over them.

The war for independence

The Angolan people reacted to the submission and began to form independence movements. The first was the MPLA (Movement for the Liberation of Angola), in 1956, at the behest of Agostinho Neto, a Portuguese dentist; the movement found a following in the center-north of the country, among the Mbundu, the assimilates, that is the few natives who had managed to obtain Portuguese citizenship and the mestizos.

In 1962, the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola) was led by Holden Roberto, who enjoyed the support of the Bakongo, an ethnic group residing in the northeast, on the border with Congo, which was formed.

The last group, UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), was created as a result of a split within the FNLA, which occurred in 1966, and led by Jonas Savimbi, a Swiss political scientist. The reason for the split seems to lie in the fact that while Roberto wanted to keep the revolt within the borders of the Kingdom of Congo, Savimbi believed in the need to spread it outside as well, in the territories that are now part of the state of Angola.

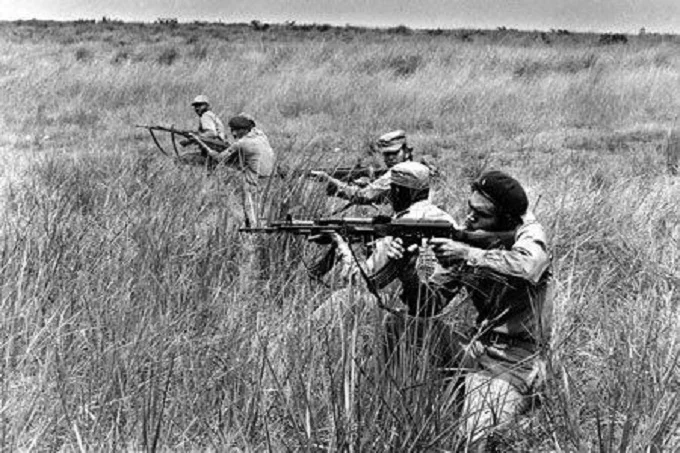

In 1961 began the armed clashes between the Portuguese and the Angolan rebels and between the independence groups. The ideological positions of the three groups were very different, and if the MPLA declared itself Marxist and enjoyed the support of Cuba and the Soviet Union, the FNLA received aid from the United States, strongly desired by President Ford, China, and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), thanks to family connections between Roberto and General Mobutu. UNITA, the last to arrive, retained the FNLA’s international backers and won the cooperation of Zambia.

The life of a colony, it is known, is strongly conditioned by the events of the motherland, and therefore, it was only in 1974, when in Lisbon the Carnation Revolution ousted the dictator Salazar, restoring democracy, that it was decided to proceed with the process of decolonization and with the Alvor Accords of January 1975, it was sanctioned that Angola would have obtained independence on November 11 of the same year.

The agreement also stipulated that all three groups that had participated in the struggle for independence should be part of the new government of free Angola, but this point was immediately ignored, and the months that followed were full of clashes between the parties in the race for power, always with the collaboration of various international players, to which was added South Africa, which sided with the United States in favor of the FNLA.

The classic Cold War scenario was also emerging in Angola, in fact, the Soviet Union, frightened by the possibility that the FNLA could take power, increased aid to the MPLA and, shortly after, Cuba was forced to intervene by an invasion of the South African military wanted by Washington.

Whoever would have Luanda in hand on Independence Day would have seized power. This was the principle that dictated the victory of the MPLA, which had conquered the city the previous day, November 10, 1975. It was Agostinho Neto who proclaimed the birth of the Popular Republic of Angola.

The civil war

A bitter and seemingly endless civil war replaced the war for liberation from Portuguese rule; the three groups that had fought for the same cause, but never together, between 1961 and 1975, hated each other more than ever.

Throughout the 27 years of civil war, Neto’s ruling movement and UNITA clashed bitterly while the FNLA took a back seat. Throughout the first part of the conflict, until the fall of the Soviet Union, the strategic and economic importance of the area and other African territories was evident in the confrontation between the two major blocs that were protagonists of the Cold War.

In 1979, Neto died and was replaced by José Eduardo Dos Santos, but the situation remained almost unchanged. Shortly before the Cubans rushed to the aid of the MPLA and the militants of UNITA had intensified the clashes: people were fleeing, in the areas controlled by UNITA, on the border with Namibia, many men and young people were killed by the Cubans to prevent them from enlisting with that movement, and entire villages were exterminated thanks to planes loaded with napalm.

Shortly after South Africa intervened again, maintaining a strong presence in Angola from 1981 to 1986, and the Soviets responded with new economic and military aid to the MPLA; the United Nations condemned the South African actions. Continuous attacks from one faction to another followed one another relentlessly in various parts of the country. The more international support grew, the more distant the possibility of putting an end to it.

In 1988 the New York Agreements, also known as the Tripartite Agreement on Angola, signed at the United Nations headquarters, which saw as protagonists the People’s Republic of Angola, Cuba, and South Africa, sanctioned the independence of Namibia (previously under the control of South Africa) and put an end to the participation of Cuban and South African troops in the conflict, allowing the United Nations to send a peacekeeping mission, the United Nations Angola Verification Mission.

The following year, thanks also to the participation of the Congolese leader Mobutu, a meeting between Savimbi and Dos Santos was possible, which led to the Gbadolite Declaration, which provided for a ceasefire in view of possible future peace agreements. UNITA eventually decided not to respect it.

Meanwhile, the MPLA was changing. It had abandoned Marxist ideology, the one-party regime had been eliminated, democracy and respect for the law were placed at the base of the country’s political system.

In 1991 a new meeting between Savimbi and Dos Santos took place in Lisbon and ended with the signing of the Bicesse Agreements, in which the terms and modalities of the democratic transition were described, and elections were scheduled for the following year. But the double-shift system that was supposed to decree the beginning of a new period for Angola was the cause of immense bloodshed.

UNITA denounced the violent and intimidating behavior of its opponents, who were willing to do anything in order not to lose power and, in response, decimated the population of some areas strongly linked to the government, and then proceeded to indiscriminate bombing of towns and villages; in the meantime, government forces were carrying out ethnic cleansing with the intent to decimate Savimbi’s supporters.

The second attempt at peace took place in 1994 with the Lusaka Protocol, desired by Savimbi himself, having realized the terrible conditions in which his group was living, in which the government of Luanda and UNITA agreed to disarm the movement and showed their intention to find a national reconciliation through the transformation of UNITA in a peaceful political actor to reach the formation of a government of national unity. Unfortunately, once again, clashes reopened.

In the new millennium, UNITA has become infamous for its illicit trafficking of arms and diamonds, recruiting young people into its ranks, and exploiting mine workers. It has continued to attack government forces and civilians to demonstrate its strength to gain a prominent position in any decisive peace talks.

The group ceased its activities only in 2002 when government forces killed Savimbi and the MPLA decided to reopen the dialogue with the new leadership, first with a ceasefire agreement, then with a memorandum of understanding to reaffirm what had been foreseen by the Lusaka Protocol.

References:

- Africa since 1940: The past of the present; F. Cooper

- The EU and Africa: from Eurafrique to Afro-Europa; A. Kebajo, K. Whiteman; Hurst & Company, London

- Foreign Intervention in Africa. From the Cold War to the War on Terror; E. Schmidt; Cambridge

- https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/angola