Caroline of Brunswick: Why King George IV of England hated his wife

Although she was well-liked by many of her people, Queen Caroline’s husband hated her. When she attempted to attend King George IV’s coronation at Westminster Abbey, the door was shut in her face. She was unable to enter.

History

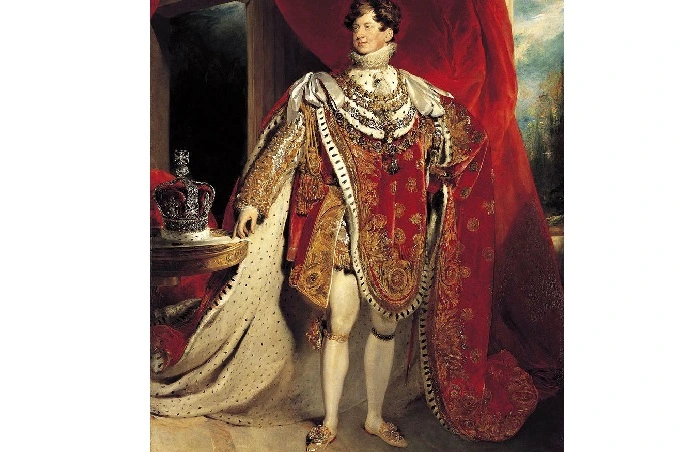

At the time of his coronation at Westminster Abbey on the 19 of July 1821, King George IV was still serving as Prince Regent following his father’s death. The coronation of George IV was the most expensive and elaborate in the history of the United Kingdom. The event began at Westminster Hall and was followed by a parade to Westminster Abbey, which was watched by the general public.

Along the walk, the royal herbalist and her six maids spread flowers and aromatic herbs in an effort to ward off the plague and pestilence that was sweeping over the land. After them came officials from the administration, the three bishops who were traveling with the king, the barons of the Cinque ports, the peers of the kingdom, and various other dignitaries. But one person was still missing: Queen Caroline, who was King George IV’s wife.

Her carriage arrived at Westminster Hall promptly at six o’clock in the morning. Although the troops and authorities who were standing at the door felt “anxious excitement,” a group of the crowd that was sympathetic to her welcomed her with applause. When the head of security approached Caroline and asked for an invitation card, she responded that she did not require one due to her position as queen. Despite this, she did not receive the position. The attempts of Queen Caroline and her Lord chamberlain to enter Westminster Hall by a side door and the neighboring House of Lords (which was connected to Westminster Hall) were also unsuccessful. They tried to enter the building through both of these paths.

And despite Caroline’s endeavors, the entrance to Westminster Abbey slammed shut in her face as she attempted to enter the building. The group belonging to the queen was obliged to retreat.

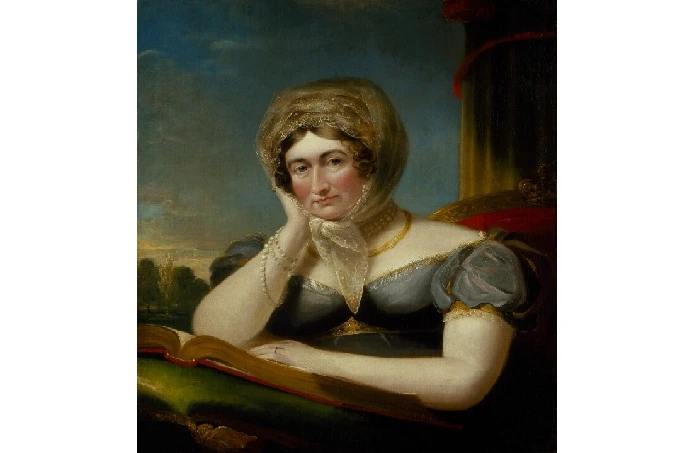

Caroline of Brunswick

The 17 of May 1768 was the day when Caroline was born. At the age of twenty-six, she engaged with the man who would one day become King George, but they were never seen together. The profligate King George had amassed debts of £630,000, which was a huge figure at the time, and the British Parliament only consented to repay these debts provided the successor to the throne married and produced an heir. This circumstance led to the union of the two families. It is stated that when they eventually met a few days before their wedding in April 1795, George was repulsed by her appearance, body odor, and lack of refinement. The wedding took place in April of that year. Both parties shared the hate.

Prince George was already married. He had married Maria Fitzherbert, but because his father had not consented, the marriage was invalidated under English civil law. Mrs Fitzherbert, as she was called, was Catholic, so had the marriage been approved and valid, George would have lost his place in the British line of succession because of laws that did not allow Catholics or their spouses to become monarchs.

However, Pope Pius VII declared the marriage valid regarding the sacrament. This relationship ended in 1794 with George’s engagement with Caroline. But here, too, George did not remain indebted and humiliated his wife by sending his mistress, Lady Jersey, as her maid of honor. Of this marriage, it was said that “the morning after its consummation witnessed its actual dissolution. George and Caroline’s only child, Princess Charlotte, was born just nine months after the wedding. The couple separated shortly after the birth of their daughter. In April 1796, the king wrote a letter to his wife to negotiate the terms of their separation.

He assured Caroline that if Princess Charlotte were to die, she would no longer have to be intimate with him to conceive another legitimate heir to the throne. He concluded, “Since we have made ourselves perfectly clear to each other, the rest of our lives will pass in uninterrupted tranquility. The marriage came to an end.

Exile

At the turn of the nineteenth century Caroline was living in a private residence near Greenwich Park, London. Over time, rumors began to circulate about her immodest and immoral behavior. It was rumored that she had given birth to a child out of wedlock, behaved lewdly and inappropriately, and sent her neighbors letters with obscene drawings. In 1806, with the support of her brothers, George brought charges against Caroline, but it was proved that she was not the mother of the boy in question, yet the investigation damaged her reputation.

Despite this investigation against her, Caroline was still a more popular figure than her husband. When George was Prince Regent, his extravagance made him unpopular with the public. He also limited Caroline’s access to her daughter and made it clear that any friend of hers would be unwelcome at the court of regency.

By 1814 the unfortunate Caroline had reached an agreement with Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh. She agreed to leave Great Britain in exchange for an annual allowance of thirty-five thousand pounds sterling until she returned. Both Caroline’s daughter and an ally in the opposition Whig political party were alarmed by her departure, for it meant that the queen’s absence would strengthen her consort’s power and weaken them. Caroline left Britain in August 1814.

Caroline remained away from Britain for six years. She traveled extensively and, early in her travels, hired an Italian courier named Bartolomeo Pergami, whom she had met in Milan. He was soon promoted to majordomo, and later Caroline moved in with him and his entire family at a villa on Lake Como. Once again, rumors swirled, this time that the couple was lovers.

Sadly, Princess Charlotte died in childbirth, and her son was also born stillborn. Caroline no longer hoped to regain her status in Britain after her daughter acceded to the throne, much less after her death. George wanted a divorce, but that was only possible if Caroline’s adultery was proven. British Prime Minister Lord Liverpool sent investigators to Milan.

The “Milan Commission” sought potential witnesses who could testify against Caroline. However, the British government sought to prevent a massive scandal and opted for a long-term separation agreement between the separated royal couple rather than granting a divorce. But before this could happen, King George III, her husband’s father, died.

Now the British government was prepared to offer Caroline fifty thousand pounds sterling to keep her out of the country, but this time she refused. Negotiations to keep her out were deadlocked over the issue of the liturgy. While King George IV was inclined to introduce Caroline to European royalty, he refused to allow her name to be included in prayers for the British royal family in the Anglican Church. After this insult, she decided to return home, and the king decided to carry out his threat of divorce.

Return of CaroIine of Brunswick

Caroline returned to Great Britain in June 1820. Large crowds greeted her as she made her way from Dover to London. George and his government became increasingly unpopular after the Peterloo Massacre and the repressive suppression of the Six Acts. It was noted that the middle and working classes were most active in supporting Caroline: She became a popular figure for the anti-government and anti-monarchist protesters who rallied around her.

The Penalties and Punishment Bill for Acts to Deprive Caroline of her Rights and Title of Queen Consort and to Dissolve Her Marriage to George was given its first reading in the House of Lords the day after she returned to the UK. The bill was passed the day after she returned to the UK. The second reading was conducted in the style of a court proceeding, complete with the calling of witnesses and their examination under oath. The conclusion of the trial was signified by the bill being passed on its second reading in November by a vote of 119 to 94. After the third reading, the number of votes received by those in favor of the motion dropped to just nine. Since Lord Liverpool was aware that the bill did not stand a good chance of being approved by the House of Commons, he decided to bury it. The Prime Minister stated that he “could not have been uninformed of the public’s attitude about this action.”

During the period of her trial that took place in the House of Lords, the crowd that greeted Caroline in her carriage cheered enthusiastically. When the divorce bill was finally overturned in November, another massive party was to celebrate. However, following a string of Whig losses in the House of Commons over January and February in 1821, they decided to drop their defense of her. When she finally attempted to attend the coronation of her husband, many people were happy to see her, but there were other people who openly hated her.

Queen Caroline death

Queen Caroline passed away just nineteen days after the coronation of her husband as king. During the procession of her funeral, there were outbreaks of violence. In her will, she stipulated that the inscription on her tombstone should read “To the memory of Caroline of Brunswick, the injured Queen of Britain.” However, this request was not honored. Specifically, the events of the last year or so of her life have brought up problems in British culture regarding the legitimate role that Parliament, the monarchy, and the people all play in the country.

A substantial portion of what took place to Caroline in the year 1820 brought to light the inequalities that women were forced to endure and mirrored the attitude of radicalism pervasive in Britain from 1815. People, particularly women, raised concerns about divorce laws that gave men preferential treatment for the offense of adultery. Political change was a goal of the radicals, and Queen Caroline served as a unifying force for the two groups.