Do Egyptians live in Scottish Neolithic village of Skara Brae?

Rocky soil, waves crashing on the shores, wastelands covered with heather… This is what most of the islands of the Orkney archipelago, located off the coast of Scotland, look like today. Only 20 out of 70 pieces of land are inhabited today, and once there was a lot of life here!

The strongest storm that hit the west coast of the island of Mainland in 1850 led not only to a series of disasters but also to the most important archaeological discoveries, which include the Neolithic village of Skara Brae.

The storm raged for several days, and when it subsided, the sailors discovered something strange from the side of a fishing schooner fishing for cod, which they had not seen before. These were the skeletons of oddly shaped stone houses, whose walls had previously been hidden under hills washed away by seawater. The fishermen told about their discovery, and the news reached London.

But the Royal Geographical Society received the message indifferently: you never know in the territory of the Foggy Albion small settlements of the Vikings, which they used as ports during their voyages. And getting to a remote and deserted area in those days was problematic.

Therefore, it was only in 1913 that the first expedition appeared on the shores of the island of the Mainland. However, at first, their backbone was made up of speleologists who decided to explore the local caves. A little later, Professor Boyd Dawkins came to the Orkney Archipelago as part of such an expedition.

Maybe the scientist would have limited himself to the study of caverns, but chance turned the development of this story in the right direction. The professor was invited to visit by Lord Belfour Stewart, the owner of the local lands, and so during the five o’clock tea – so, by the way – he mentioned the buildings in the town of Skara Brae. Dawkins became interested and went to the coast.

What he saw puzzled the professor greatly. Dawkins was well versed in history and therefore looked at the buildings in surprise. No, they were not like the buildings of the Vikings. Then what is it? Having asked the lord to take measures to preserve the settlement – storms then swept it with sand and sediments, then carried them back to the sea – the scientist hurried to London.

“And here I told the scientist-archaeologist, Professor Gordon Child, about this discovery. He first categorically stated that these were the remains of a settlement of “Picts – irreconcilable enemies of the Roman invaders and the Scots, who were forced out by the latter to these places by about the IX century”.”

Strange settlement

Indeed, such a nationality existed. Scientists suggest that its first representatives had Iberian roots, and in those distant times when there was an isthmus between the present British Isles and the continent, which subsequently sank to the bottom of the sea, they moved to the shores of Foggy Albion. But when Child arrived at the site in mid-1924, he found himself confused.

The archaeologist was alerted by the fact that the entrances to all eight preserved buildings did not exceed one meter in height. However, excavations of ancient Pictish graves showed that their average height did not differ from the height of modern people. There are also descriptions of the appearance of men of this nationality – slender dark-haired Caucasian people with long narrow heads.

The bewilderment intensified when they managed to get inside the first building – stone beds, judging by their length, could only shelter a child. And then it dawned on the scientist: in fact, this is not a Pictish village, representatives of some other nationality lived here, and the age of the houses dates back to the Neolithic era and dates back to 3100-2500 BC. By the way, in the 1970s, scientists using radiocarbon analysis confirmed Professor Child’s guess.

So, what did the participants of the first expedition see? Mica sandstone was used as a building material, and the houses were built in a rounded shape – probably in order to have less wind load. The foundation of the houses was somewhat buried in the ground, which allowed to save heat, and the structure itself was surrounded by an earthen mound, again for better thermal insulation.

Unfortunately, there were problems with the wood, so for the ceiling beams, firewood collected on the seashore or the bones of the skeleton of whales, which at that time lived in northern waters and which often washed up on the coast, were used. The ceiling itself consisted of stretched reindeer skins, reinforced with leather ropes, on which layers of peat were laid.

Another interesting detail is that the houses were built on piles of garbage. That is, first, a landfill was formed, and then a buried foundation was built in its place. It is quite possible that for stability and, again, thermal insulation.

I must say that at that time, the locals were in good living conditions. The rooms were heated using a furnace, which was heated with the same peat. However, the room was one large room with an area of approximately 40 square meters, from which a pantry and… a toilet were separated. Yes, there was a fairly well-built sewage system in the settlement, and fresh water, thanks to rains and with the help of drains, accumulated in huge stone tanks.

The main food of the aborigines was fish, which was caught from the shore – after all, there was nothing to build wooden ships from. Dried venison was harvested in reserve and for the winter. In addition, the climatic conditions of that time promoted agriculture, and flour tortillas made up a significant part of the diet of local residents. The furniture was made of stone by skilled stonemasons – cabinets, chests, and beds.

Who are they?

So it could be assumed that there was a large settlement on the shore of the bay, which gradually (or almost immediately?) was swallowed up by the sea. It was not possible to establish what the aborigines looked like. Most likely, their burial grounds, unlike the Picts’ graves preserved on the islands, also disappeared under the water column. So who were they, the first Neolithic Orkneyans?

Scientists have suggested that they arrived on the shores of Scotland on a ship that crashed on coastal rocks during a storm. And since there was nothing to build a new ship from, they had to settle in a new place. Some food for thought was provided by the excavations on the territory of Skara Brae.

For example, it turned out that the eighth surviving building, whose interior was divided into cells, was a workshop where craftsmen made the simplest production tools, such as stone axes or fish bone needles, as well as key rings and jewelry.

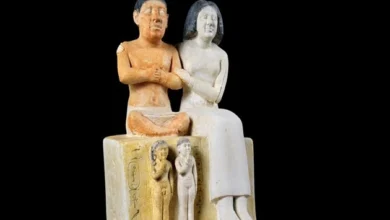

But it was not possible to explain the purpose of bone and stone artifacts depicting pyramids. And then the “Egyptian version” was born. Scientists have suggested that emigrants from Egypt settled in these places at one time – more precisely, representatives of the caste of priests.

The following arguments were given as arguments. Firstly, the level of construction was striking, characteristic at that time only for Egypt. Further, in its style and appearance, the pottery found during excavations very much resembled the products of ancient Egyptian potters, and the people themselves, who lived at that time on the shores of the Gulf of Suez, were short by today’s standards, something about 150 centimeters. Hence the small entrances to the dwellings.

Finally, scientists were particularly interested in drawings and inscriptions made on walls, cabinets, and beds. The first resembled a lunar calendar tied to the image of the Solar system and the signs of the zodiac, which was known to Egyptian astronomers. But the inscriptions were first considered to be made by runic symbols. But upon closer analysis, it became clear that only sixteen letters were used in runic symbols, and the signs of Orkney letters rather resembled ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Unfortunately, the Egyptians did not bother to keep chronicles describing the migrations, and the few papyrus pieces of evidence that were created, for the most part, were destroyed by Alexander the Great during the capture of Heliopolis. So the mystery of the island, most likely, will never be solved.