Japanese are not native to Japan, then who is native to Japan?

Everyone understands that Americans, like the existing population of South America, are not native to the country. Did you realize that Japanese people are not native to the country? Before them, who had resided in these locations?

Before them, the Ainu lived here, a strange race whose origins are still shrouded in mystery. The Ainu and the Japanese coexisted for a long period until the latter drove them to the north.

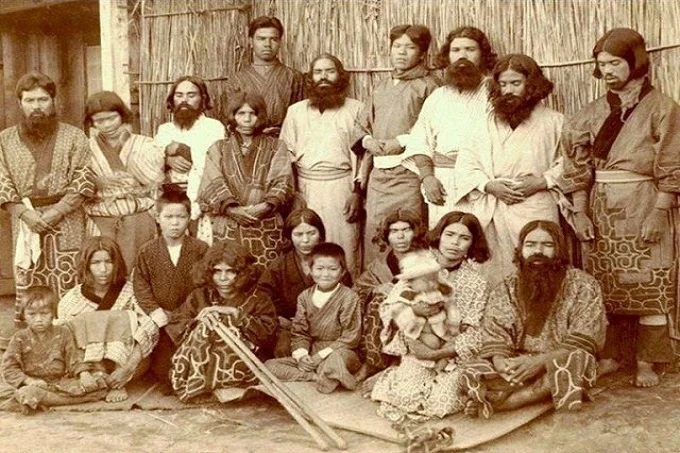

Ainu settlement towards the end of the nineteenth century

Written records and countless names of geographical things whose origins are related to the Ainu language attest that the Ainu were the ancient lords of the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands.

Even Japan’s national emblem, Mount Fujiyama, is named from the Ainu term “fuji,” which means “deity of the hearth.” The Ainu are said to have arrived on the Japanese islands about 13,000 BC and established the Neolithic Jomon civilization.

Instead, the Ainu did not farm, relying on hunting, gathering, and fishing for sustenance. They lived in little communities separated by great distances. As a result, they lived in a large region that included the Japanese islands, Sakhalin, Primorye, the Kuril Islands, and the south of Kamchatka.

Mongoloid tribes landed on the Japanese islands about the third millennium BC and were the progenitors of the Japanese. The newcomers brought a rice culture with them, which nourished a huge population in a little region. As a result, the Ainu’s existence became difficult. They were compelled to relocate to the north, abandoning their ancestral territories to the colonialists.

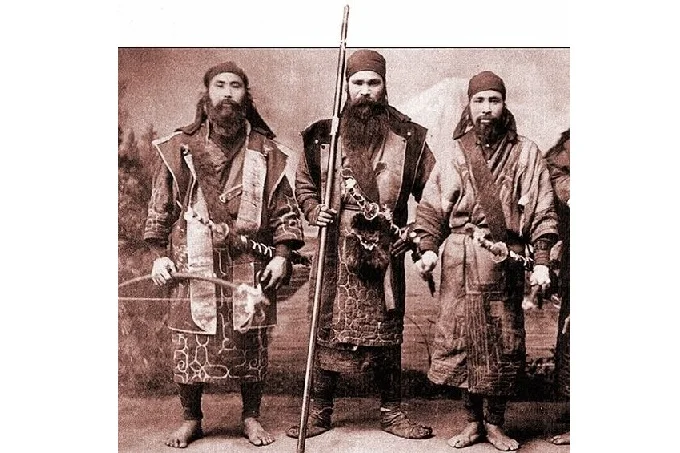

The Ainu, on the other hand, were skilled warriors who could expertly use bow and sword, and the Japanese were unable to vanquish them for a long time. For approximately 1500 years, to be exact. The Ainus were skilled with two swords and wore two daggers on their right thigh. One (cheiki-makiri) was used to conduct hara-kiri or ritual suicide.

After learning a great deal about the art of battle from the Ainu, the Japanese were only able to vanquish them after the advent of cannons. The samurai code of honor, the ability to wield two swords, and the hara-kiri rite, all of which seem to be typical of Japanese culture, were really taken from the Ainu.

Scientists are still debating the Ainu’s origins

However, these people are already established to be unrelated to other indigenous peoples of the Far East and Siberia. Their look is characterized by exceptionally thick hair and a beard in males, both of which are lacking in Mongoloid racial members. Because they had comparable face characteristics, it was thought that they shared common ancestors with Indonesians and Pacific Islanders for a long time. However, a genetic study has ruled out this possibility as well.

The first Russian Cossacks who landed on Sakhalin’s island confused the Ainu for Russians, therefore they didn’t look like Siberian tribes, but rather Europeans. The people of the Jomon period, probably the Ainu’s forefathers, were the only group of people with whom they had a genetic link out of all the studied varieties.

The Ainu language is likewise mostly absent from today’s linguistic landscape, and they have yet to find a fitting home for it. It turns out that the Ainu lost communication with all other peoples on Earth during their lengthy isolation, and some experts even classify them as a separate Ainu race.

At the end of the 17th century, the Kamchatka Ainu had their first encounter with Russian traders. In the 18th century, relations between the Amur and North Kuril Ainu were formed. The Russians were seen as allies by the Ainu, who were of a different race than their Japanese foes, and by the middle of the 18th century, more than a half-thousand Ainu had obtained Russian citizenship. Because of their superficial similarities, even the Japanese couldn’t tell the Ainu apart from the Russians (white skin and Australoid facial features, which in a number of features are similar to Caucasians).

The Russian State’s Spatial Land Description, created under Russian Empress Catherine II, covered not only all of the Kuril Islands but also the island of Hokkaido in the Russian Empire.

The explanation for this is that ethnic Japanese were not even there at the time. Following the expeditions of Antipin and Shabalin, the indigenous people, the Ainu, were documented as Russian subjects.

The Ainu fought with the Japanese not just in the south of Hokkaido, but also in the north of Honshu. In the seventeenth century, the Cossacks explored and taxed the Kuril Islands. So that Russia may demand Hokkaido from Japan.

The fact that the people of Hokkaido were Russian citizens was mentioned in a letter from Alexander I to the Japanese Emperor in 1803. Furthermore, there were no complaints, much alone a formal protest, from the Japanese side. Hokkaido, like Korea, was a foreign land for Tokyo. The Ainu with Russian names and surnames came out to greet the first Japanese who landed on the island in 1786. And not just any Christians, but Christians who are devout!

The earliest Japanese claims to Sakhalin were made in 1845. Then, Emperor Nicholas I, launched a diplomatic counter-offensive. Only the weakness of Russia in the ensuing decades allowed the Japanese to occupy the southern section of Sakhalin.

It’s worth noting that the Bolsheviks denounced the previous administration in 1925 for handing over Russian regions to Japan. As a result, historical justice was only restored in 1945. The Soviet army and navy used force to settle the Russian-Japanese territorial dispute.

In 1956, Khrushchev signed the Joint Declaration of the Soviet Union and Japan, which stated in article 9: “The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics agrees to the transfer of the Habomai Islands and the Sikotan Island to Japan, in accordance with Japan’s wishes and taking into account the interests of the Japanese state; however, the actual transfer of these islands to Japan will be made after the conclusion of the Peace Treaty between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Japan.”

The purpose of Khrushchev was to demilitarize Japan. In order to remove American military sites from the Soviet Far East, he was ready to sacrifice a few tiny islands.

Obviously, we aren’t talking about demilitarization anymore. On its “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” Washington has a grip. Furthermore, after the Fukushima nuclear power plant tragedy, Tokyo’s reliance on the US became even more. If that’s the case, then the free transfer of the islands as a “goodwill gesture” is losing its appeal.

It is permissible to deviate from Khrushchev’s assertion and make symmetrical claims based on well-known historical facts. Shaking the antique scrolls and manuscripts, as is customary in such situations.

A refusal to give up Hokkaido would be a cold shower for Tokyo. It would be required to contend in the negotiations about their own region at the time, rather than Sakhalin or even the Kuriles.

You’d have to defend yourself, make explanations, and demonstrate your innocence. As a result, Russia would shift from diplomatic defense to attack mode.

Furthermore, China’s military activities, the DPRK’s nuclear aspirations and military preparation, as well as other security issues in the Asia-Pacific area, would provide yet another incentive for Japan to sign a peace treaty with Russia.

However, when the Japanese saw the Russians for the first time, they dubbed them Red Ainu (Ainu with blond hair). The Japanese only understood the Russians and the Ainu were two separate peoples around the turn of the nineteenth century. The Russians, on the other hand, thought of the Ainu as “hairy,” “dark-skinned,” “dark-eyed,” and “dark-haired.” The earliest Russian scholars characterized the Ainu as being comparable to Russian peasants with black complexion or more like gypsies.

During the 19th century Russo-Japanese Wars, the Ainu allied with the Russians. The Russians, however, abandoned them to their destiny following the loss in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. The Japanese killed hundreds of Ainu, and their families were forcefully relocated to Hokkaido. As a consequence, during World War II, the Russians were unable to recover the Ainu. After the conflict, just a few Ainu representatives chose to remain in Russia. Over 90% of the people fled for Japan.

The Kurils, as well as the Ainu who lived on them, were given to Japan under the conditions of the St. Petersburg Treaty of 1875. On September 18, 1877, 83 North Kuril Ainu landed at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, opting to stay under Russian control. They declined to relocate to the Commander Islands reserves, as offered by the Russian authorities. They then trekked for four months, beginning in March 1881, to the town of Yavino, where they eventually settled.

The settlement of Golygino was established afterward. In 1884, nine more Ainu came from Japan. According to the 1897 census, there were 57 people in Golygino (all Ainu) and 39 people in Yavino (33 Ainu and 6 Russians). The Soviets razed both settlements, and the residents were relocated to Zaporizhzhia in the Ust-Bolsheretskiy region. As a consequence, the Kamchadals amalgamated three ethnic groups.

The North Kuril Ainu are Russia’s most populous subgroup of Ainu. In Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the Nakamura family (paternal South Kuril) is the smallest, with just 6 members. A few Ainu on Sakhalin identify as such, but the majority of Ainu do not.

The majority of the 888 Japanese people residing in Russia (according to the 2010 census) are of Ainu descent, although they are unaware of this (purebred Japanese are allowed to enter Japan without a visa). The Amur Ainu of Khabarovsk is in a similar predicament. None of the Kamchatka Ainu is said to have survived.

The Soviet Union removed the ethnonym “Ainu” off the list of “alive” ethnic groups in Russia in 1979, thereby declaring that these people had died out on Soviet soil. According to the 2002 census, no one used the ethnonym “Ainu” in the K-1 census form fields 7 or 9.2.

The Ainu male line has the most direct genetic linkages with the Tibetans – half of them are carriers of the nearby haplogroup D1 (the D2 group itself essentially does not exist beyond the Japanese archipelago) – and the Miao-Yao peoples in southern China and Indochina, according to research.

In terms of female (Mt-DNA) haplogroups, the Ainu have the U group, which is also found in modest quantities in other East Asian peoples.

Approximately 100 persons attempted to register as Ainu at the 2010 census, but the Kamchatka Krai authorities rejected their claims and listed them as Kamchadals.

In 2011, the head of the Kamchatka Alinsky community, Alexei Vladimirovich Nakamura, wrote to the governor of Kamchatka, Vladimir Ilyukhin, and the chairman of the local duma, Boris Nevzorov, requesting that the Ainu be added to the Russian Federation’s List of Indigenous Minorities of the North, Siberia, and the Far East. The request was turned down as well.

According to Alexei Nakamura, 205 Ainu were identified in Russia in 2012 (compared to 12 in 2008), and they, like the Kuril Kamchadals, are striving for formal recognition. Many decades ago, the Ainu language died out.

Only three people on Sakhalin spoke Ainu fluently in 1979, and the language was nearly extinct by the 1980s.

Although Keizo Nakamura spoke Sakhalin-Ainu proficiently and even translated papers into Russian for the NKVD, he did not teach his son the language. Asai, the last person to speak Sakhalin Ainu, died in 1994 in Japan. Until the Ainu are acknowledged as a people with no nationality, they are honored as ethnic Russians or Kamchadals.

As a result, in 2016, both the Kuril Ainu and the Kuril Kamchadals were stripped of their hunting and fishing privileges, which the Far North’s tiny peoples formerly enjoyed.

There are just approximately 25,000 Ainu people remaining today. They dwell mostly in Japan’s north, where the local people have virtually totally integrated.