Conquering independence in 1783, the young United States of America immediately embarked on an expansionist policy, expanding in every possible direction in every possible way. The fact is that there was no power left on the whole continent capable of winning a decisive military victory over the new player. Just kidding, the U.S. was born in a war against the most powerful empire in history.

However, there was another significant difference between the now American citizens of the new country and the colonizers in the service of this or that royal court. The Americans called themselves by that name, directly indicating their intentions: they were here forever; now, this was their home, which they had built with their own hands and defended with salvos of arms. Colonies, however, are never eternal, and colonizers work solely for money as long as the empire can support them.

The slogan Don’t tread on me emerged during the initial process of American self-identification as a nation. “Don’t tread on me,” they say, “We may be as small as a rattlesnake, but if you step on us, we will unite, bite back, poison you, and you will surely die, while we, even at our losses, will survive. Don’t step on it; all this land from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific is ours; we crawl, walk, and fly here.”

There was a problem, though: most of the current U.S. territory did not yet belong to them and was not mapped at all. At the time, the Wild West fully justified its name, but by the early 19th century, its days were numbered.

Louisiana, no one wanted

In 1800, representatives of the Spanish Crown and the French Republic met behind closed doors in the highest offices. The “Treaty of San Ildefonso” details were never disclosed, so we can only guess why Spain gave France vast territories in North America. We are talking about Louisiana, which at that time was much wider than the state of the same name today. It is thought that it was simply unprofitable and that the Spanish Empire was not having its best days; this sounds all too familiar and even trite.

Perhaps French First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte made some arguments that the Spanish court dared not oppose. No wonder, in those years, many of the courts of the great and rising European powers could not resist France’s impetuous and charismatic leader.

Around the same time, former slave Jean-Jacques Dessalines leads a slave revolt in Haiti, defeating a relatively small French colonial force. Twenty-thousand reinforcements soon arrive on the island, gradually wiped out by local diseases and formerly enslaved people unwilling to obey.

Soon Jean-Jacques Dessalines declares himself president for life and then emperor. Haiti would become a country for blacks only, where whites would already be purposely slaughtered, calling them “colored. This remains the only time in world history when enslaved Black people won their independence and built their own country, which immediately fell into a dictatorship, where it remains to this day. Later the mob will also tear apart their liberator, who will prove no better than the former masters. Here the rule that a faithful slave does not dream of freedom but of becoming an enslaver is fulfilled.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines may not have had such global aims, but it was largely due to his rebellion that France lost much of its military presence in the New World. Then it was his turn to cede Louisiana to the United States government. The official reasons were the same; of course, damned Louisiana was again unprofitable and generally unnecessary. Perhaps the proximity to English possessions and the continental war in Europe gave American diplomats additional and persuasive arguments.

France sold 2 100 000 km2 of land for 15 million dollars, which is 7 cents per hectare. To better understand the scale, it should be noted that this is more than 20 percent of the territory of the modern United States and twice what the U.S. was in 1803. With the new acquisitions came the corresponding needs for their development, but at least exploration was needed to begin with. The fact is that the territory of Louisiana belonged only on paper to one country or another; in reality, its western boundaries had not even been precisely defined. No government expedition had yet reached it, and the time had finally come.

Corps of Discovery

Such a title is mildly confusing: discovery seems to be about geography, botany, and mapping. Images of people with glasses over their eyes and a pen in their hand come to mind. However, the word “corps” evokes completely different associations; it is something about guns, bayonets, and ranks. Created at the behest of President Thomas Jefferson in 1804, the Corps of Discovery was a unit of the U.S. Army that included civilian specialists in various sciences.

The Corps had commercial and scientific objectives, among which were to explore and map the acquired lands of Louisiana, find the most convenient routes to advance inland, and reach the West Coast. It was to determine how to profit from the new lands, get to know the local tribes, and study the flora and fauna of the Wild West.

Among other things, Thomas Jefferson believed it was essential to establish a physical U.S. presence in the new lands as soon as possible. This would have meant a new policy toward Louisiana, which had too often changed hands, with much of its territory never used in any way. A permanent American presence would, once and for all, discourage the European colonial powers from laying claim to the region in the future.

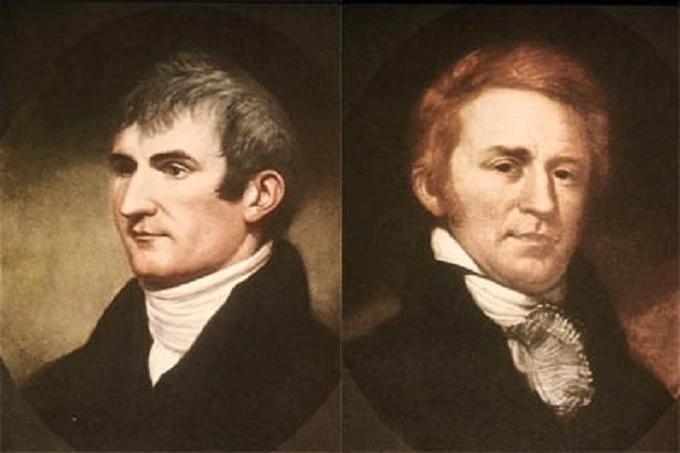

The expedition was led by Captain Meriwether Lewis, personal secretary to the president of the United States, who invited his longtime friend Lieutenant William Clark as his assistant and deputy. Clark was a captain, too, but the army system required a clear hierarchy, and there could not be two men of the highest rank in the Corps at once. Nevertheless, the friends agreed that they would keep this position secret from the rest of the expedition, for whom Clark would remain captain on an equal footing with Lewis.

Preparation took a year; while the carpenters built the boat, Lewis engaged in a basic mastery of various sciences, from astronomy to medicine. In addition, he studied the diary of Moncacht-Apé, who had supposedly taken a similar route a century earlier. The entries were fragmentary with lengthy gaps, perhaps misleading the commander. The captain envisioned the journey ahead as a long but relatively easy rafting trip, unaware that Missouri did not flow into the ocean and that he would have to traverse the Rocky Mountains, preferably with the boat preserved for later travel. Even this information, however, would hardly stop the expedition. Provisions with the necessary tools are loaded, and silver peace medals with gift sets or 46-caliber shotguns are prepared for the Indians. The choice is theirs. In addition to the men, the expedition included a Newfoundland dog named Seaman, an excellent helper in the hunt and a good swimmer capable of saving a man.

On May 14, 1804, a shot was heard: a signal to sail. Having waited for the end of the deal and the official transfer of Louisiana to U.S. jurisdiction, the expedition of 45 men leaves Dubois Camp. Some 6,000 miles of uncharted territory lie ahead, the same amount in the opposite direction.

Lewis and Clark: Up Missouri

The boat had a sail, which made it easier for the rowers to work in a tailwind, but you had to work with oars most of the way. Soon after the first incident occurs, three expedition members appear before a court martial for deserting camp. The punishment of 25 lashes demonstrates that this is not a walk on the river but a scientific and military expedition. Everyone is invited to disembark at La Charrette, the last of the European settlements on Missouri, but the crew remains in full force.

The next such incident will occur at a considerable distance from civilization. The defendants are the same, but the sentence is much harsher, with the instigator receiving 100 strokes for stealing and drinking whiskey, the accomplice half as many. According to the official version, Sergeant Charles Floyd soon dies from acute appendicitis, though some historians doubt it. Either way, he becomes the first and only member of the expedition to die. Floyd’s burial, as well as the cliff and a small river named in his honor, is in favor of the official version and the absence of personal conflict.

In late August 1804, the expedition reached the borders of the Great Plains, where deer, bison, and beavers were abundant. Lewis and Clark encountered several previously unknown tribes on a section they had already traversed. The locals were generally friendly to the travelers, but firearms were of more interest to them than token gifts and medals. Nevertheless, the first contacts were rather successful, at least without bloodshed, but the deeper into the Wild West, the more problems arose.

The expedition had already been warned about the warlike Lakota( Sioux ) people, who prevented free trade on the river, but the way was through their lands anyway. The gifts they had prepared did not impress their hosts, and they demanded a boat or several crew members as enslaved people. One of their horses disappeared, and they believed the Sioux were responsible. Afterward, the two sides met, and there was a disagreement; the Sioux asked the men to stay or give more gifts before being allowed to pass through their territory. They came close to fighting several times, and both sides finally backed down, and the expedition continued to Arikara territory. Clark wrote they[clarification needed] were “warlike” and were the “vilest miscreants of the savage race.”

Before wintering, after reaching Mandan territory, the main boat and part of the crew were sent back to St. Louis. With the Rocky Mountains ahead, there was no further to go, which became a surprise and a problem. For the next few days, the expedition searched for a place to camp, attracting more and more attention from the locals. They proved less belligerent than the Lakota and even helped by pointing out the best place for a winter fort. At one point, a paler, European face appeared among the motley faces of the Mandan. It was a French-Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau, whom Lewis had now hired as an interpreter. Joining him on the expedition was the first woman, a 16-year-old Sacagawea, whom the zookeeper had either won in a card game or picked up somewhere while rescuing from wild beasts. This story remains unresolved, but Sacagawea was stolen from her native tribe and somehow married to this European. Soon Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was born, whom the young mother would carry on her back the rest of the way.

The farther the expedition moved through the mountains, the more familiar the places seemed to Sacagawea. She began to play the role of guide and negotiator. The presence of a woman in the group served as a signal of peaceful intentions, for it was customary for the natives to leave all women at home if the tribe was going to fight. In the summer of 1805, moving through the Shoshone territory, a fateful meeting took place. The chief’s sister, who arrived to negotiate, recognized Sacagawea, with whom she had been taken prisoner but managed to escape. Lewis will note that the meeting between these men was truly touching in his diary. The Shoshone provided the travelers with necessary provisions and helped repair the canoes, which rocks had worn out.

On November 7, 1805, the expedition saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time and soon reached it. It was urgent to choose a place for another wintering and to build a fortification. This time the expedition no longer had enough gifts or other valuables to barter for food from the nearest tribes. This meant that if the camp was in a bad location and there were no beasts to hunt nearby, they might all die. It was decided to choose one of the two most promising options by popular vote. Shoshone Sacagawea and the Clark’s slave York were allowed to participate in this vote, which may have been the first time at all in the history of the United States on an official level. Thus Fort Clatsop came into being, and the striped flag began to develop on the westernmost frontiers of the United States.

Consequences and Fates

Although Lewis and Clark returned as national heroes, their names would soon fall out of the focus of contemporaries and history until the early 20th century. The nation would be busy developing the open Wild West, followed by the Gold Rush and the Civil War. Nevertheless, the time has put everything in its place, returning the heroes to their deserved glory. Today, the two are the most famous discoverers in the United States, with dozens of artificial and natural sites named after them.

At Clark’s invitation, Sacagawea visited St. Louis in 1809 before returning to Fort Lisa. She died in 1812 of an unknown illness, presumably fever. However, there are two other versions; according to one of them, Shoshone returned to her native land, where she lived until her old age, or was killed in a raid on the fort in 1825. Either way, Clark became a guardian of Sacagawea’s son, giving him a higher education at St. Louis University.

Unlike all the other expedition members, who received prizes and lands, York received nothing. Clark refused to grant him his freedom and even separated him from his wife. Nothing is known of York’s final years, but another expedition tells of an encounter with a black man who held the position of chief in one of the tribes. This man said he came here for the first time with Lewis and Clark.

Meriwether Lewis was appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory by executive order in 1807. Despite extensive road building by the federal government, the governor tried to keep the western lands from being settled. It was difficult for merchants and farmers to obtain permits to operate in Louisiana, and extortion from the indigenous population often went unheeded. He died in 1809 from a headshot; it has not been established whether it was murder or suicide.

William Clark was appointed general of the Louisiana militia by the same presidential decree that also authorized him to serve in the Anglo-American War of 1812. Clark was a participant in that conflict. Since taking office as governor of the Missouri Territory, this portion of Louisiana, formerly divided, has become the largest portion. Beginning in 1822 and continuing until 1838, he served as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs. He passed away in 1838.

Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau received an education and pursued a career as a shepherd and a hunter like his father before him. Because he possessed Shoshone blood, he could readily develop relations with the Indians. During the 1840s, he took part in the “Gold Rush” phenomenon, walking the entire distance from the East to the West. In addition, he served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War.