Why portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte are considered pure propaganda

The period of Napoleon’s reign in France was marked by the almost industrial production of his portraits. The French state commissioned painters and sculptors who created hundreds of images of Bonaparte.

Most of these portraits had a clear political and propaganda role, if not all. The focus was on the personality of Napoleon and the legitimization of his own rule in France. In this article, I will discuss how the 19th century witnessed the emergence of a new kind of self-promotion through art, pioneered by the portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte.

A brief biography of Napolean

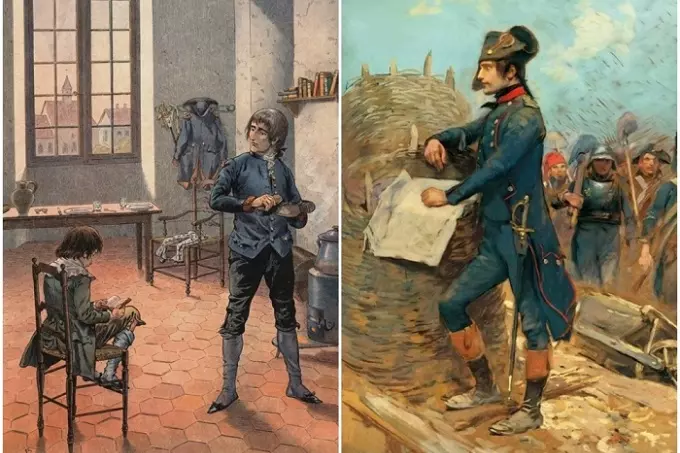

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on 15 August 1769 on the island of Corsica in a family of not very wealthy aristocrats. At the age of fifteen, he was sent to the Royal Military Academy in Paris. At the age of sixteen, he began his military career as a second lieutenant, training in the best artillery unit of the French army.

After the start of the French Revolution, Napoleon returned to Corsica. Inspired by revolutionary ideals, he immediately got involved in Corsican politics. Bonaparte soon became the leader of a faction opposed to the governor of the island, Pasquale Paoli. Unfortunately for him, Paoli proved to be a tough opponent. After the victory over Napoleon, the Corsican Assembly declared the entire Bonaparte family traitors and expelled them from the island.

Once again, on the French mainland, Napoleon continued his military career. Having won his first great victory at only twenty-four, having liberated the city of Toulon, he became a hero of revolutionary France. Two years later, in 1795, the young Bonaparte crushed an uprising of national guards and mobs in Paris. This feat earned him the rank of general in command of the army of Italy at the age of twenty-six.

Antoine Jean Gros

The earliest monumental portraits commissioned by General Bonaparte were painted during his campaign in Italy. One such painting of Bonaparte, which is one of the most representative examples of Napoleon’s propaganda as a general, was painted by Antoine-Jean Gros. The artist finished the painting titled “Bonaparte on the Pont d’Arcol” in 1797.

This portrait represents one of the foundations of the Napoleonic legend, the Battle of Arcole, and Bonaparte himself leading an attack behind enemy lines. According to the tradition of a military portrait, the model should be in a standing position, looking at the viewer, in the background is a distant battlefield. Gros departs from this tradition to demonstrate the heroic deed of Napoleon. With a flag in his left hand and a sword in his right hand, the general heads towards the enemy, but looks back at his own troops on the right. Bonaparte runs in front of two conflicting parties, but still manages to remain calm and fearless. The background remains blurry, fuzzy.

Battle of Arcole

From a historical point of view, the Battle of Arcola was one of the heaviest victories during the Italian campaign. The French soldiers were demoralized by food shortages, lack of reinforcements, a larger Austrian army, and news of casualties elsewhere in Europe. Seeing the bridge, some French officers, including Napoleon among them, decided to speak to their soldiers to encourage them to break through. The idea of storming the enemy positions was quickly abandoned, and Napoleon fell into the swamp during the Austrian counterattack. After being pulled out of the mud by his officers, he borrowed a horse and rode off to change. Despite the disastrous results, this event became the focus of Napoleon’s personal propaganda.

There is an obvious difference between the portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte and what actually happened: the historical general retreats from the battlefield in disgrace. This indicates Napoleon’s desire to present himself as a leader whose soldiers are loyal and to position himself among heroic commanders, both past and present. The self-promotion of Gros’s portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte would not have been possible without the cultural and political changes that took place in France before and during the revolution.

Old traditions

In the second half of the eighteenth century, France adopted the veneration of the canon of great men. The process of creating national heroes was initiated by the state itself, which commissioned numerous statues and paintings. This period marked the transition of public veneration from saints and kings to philosophers and generals, whose cults are associated with their personalities and activities.

This shift began the nationalization of history, in which anyone who did something great earned public praise and glory. Praise and glory were presented in the form of monumental statues or busts in the public square. By the end of the century, both state and military leaders will be featured in a media reserved only for the monarchy. The trend toward democratization of visual representation intensified after the fall of the French monarchy during the Revolution of 1792. The standardization of iconography allowed unknown personalities, ready to sacrifice themselves for the sake of their country, to become heroes of the Revolution. These people were martyrs of freedom, victims of enemies both internal and external, and part of a cult propagated by the state.

From martyr to military hero

The cult of martyrs dominated revolutionary iconography until the fall of Robespierre, the waning of revolutionary fervor and mass mobilization. At this moment, a cult of military heroes arose, which formed the basis of the portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte.

During 1793 and 1794, the French press was inundated with anonymous figures of ordinary soldiers, not generals or commanders. Regardless of the veracity of their stories, their function was to represent the average Republican soldier, often fighting to the death against a superior and more numerous enemy. The heroism of the individual was ubiquitous in the daily press, as a reward for those who were willing to give their lives for their country and as an incentive for other citizens to act in the same way. Gros’s portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte was in keeping with these notions, based on the idea of free men overcoming any obstacle by sheer force of will alone.

Myth and destiny

Gros’s portrait of Napoleon formed the basis of an already established iconography among the revolutionary elite to whom the portrait was intended. In the painting, Napoleon, an army general in Italy, becomes the archetype of a simple infantryman and bearer of courage. Such behavior was expected from all military ranks. He is a figure who bravely carries the banner of the French Revolution, inspiring and raising the morale of his fear-stricken but loyal soldiers.

An identical description of Napoleon can be found in the newspaper that Napoleon himself published in Italy, The Courier of the Army of Italy. The same newspaper promoted the stories of ordinary soldiers at the behest of Bonaparte himself. He was not the first general to use self-promotion and dramatize his role in fighting the enemies of the revolution. However, unlike other generals, he stood out in that he gave his image the voice of fate and created an aura of myth around his character.

The painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1801, but at first, did not receive much public approval. On the other hand, Napoleon himself took it with great enthusiasm and persuaded the artist to make an engraving that would be printed. Engravings of this portrait were a huge success, and numerous editions and copies followed. Bonaparte’s own interest in engraving demonstrates his awareness of the power of the printed image as propaganda.

Another engraved version of this portrait was completed by Thomas Piroli. Although simpler, it was based on the original painting and is also dedicated to the Italian army. Thanks to these engravings, Napoleon went far beyond the Parisian salon public. This portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte could have covered all of Europe and, more importantly, his own army in Italy. Because of this, Bonaparte appointed Antoine Jean Gros as a member of the Arts Commission, set up to select and transport significant works of art from Italy back to France.

Propaganda

In this example of a portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, one can see how visual representation develops in close connection with political ambitions. Focused on the personality of those portrayed, artists such as Gros and Jacques-Louis David had to channel the ideas disseminated by Napoleon in other media into their work. Based on their work on traditional formulas of artistic expression and contemporary political, cultural and social developments, they created many dramatic performances. Consequently, in the perception and imagination of French society, these ideas elevated Bonaparte to the rank of a mythical hero.

Having laid the foundation with this portrait, Napoleon continued to shape, maintain and control his own perception among the French during his campaigns. Visual materials created during this period, as well as newspaper articles and proclamations of the general himself, inform not only about his military but also about his political and personal campaign.