Ponzi scheme: how a simple Italian postman became the “father” of the first financial pyramid and gained millions of dollars

If idleness was the engine of progress and valuable developments, then the desire to become wealthy at any cost led to the discovery of sometimes not quite honest means of obtaining money, according to one comical account of the history of civilization.

Adventurers have praised gold mines, speculation, and cryptocurrencies in various eras, but one Italian “investor” became renowned for launching a pyramid scheme. Although Charles Ponzi was not a “pioneer,” his name became synonymous with the famous and lucrative Ponzi scheme in the twentieth century.

The old has been forgotten by the new

The Ponzi scheme is a well-known financial process in which new depositors assure the profitability of the initial investors’ contributions. For example, in 1869, a famous actress Adele Spitzer advertised in the press that individuals who chose might earn a passive income by investing modest sums of money. Adele established her bank with just 100 guilders in start-up capital, which she borrowed from a friend, and three years later became one of Bavaria’s richest women. Surprisingly, she responded to any criticism by claiming that anti-Semitic opponents attempted to stop her. As a consequence, around 30,000 simpletons lost 38 million guilders.

However, the financial flames were not limited to Germany. Sarah Howe, an American lady from another continent, campaigned for women’s rights in an unusual method during the same period. She established the Ladies’ Deposit Company, a savings bank where ladies could deposit their funds. According to the official account, Sarah Howe defrauded 800 economically ignorant women, earning more than $250,000. Alternative reports, however, said the sum was twice as high (about $13 million today currency rate). Sarah was sentenced to four years in jail following the revelation, but she continued to try to conduct a similar financial operation after that.

Don’t imagine that ladies were the only ones who wanted to become rich swiftly. On the other hand, men were not only more active in recruiting “subscribers,” but they also guaranteed far bigger percentages. In 1899, for example, William Miller was nicknamed “William-520 percent” by the financial world due to his claimed record profitability. The former accountant “stole” $1 million from depositors (about $32 million at today’s currency rate). However, the official statistics might be questioned since Miller was able to find money after 5 years in jail to start a new legal company.

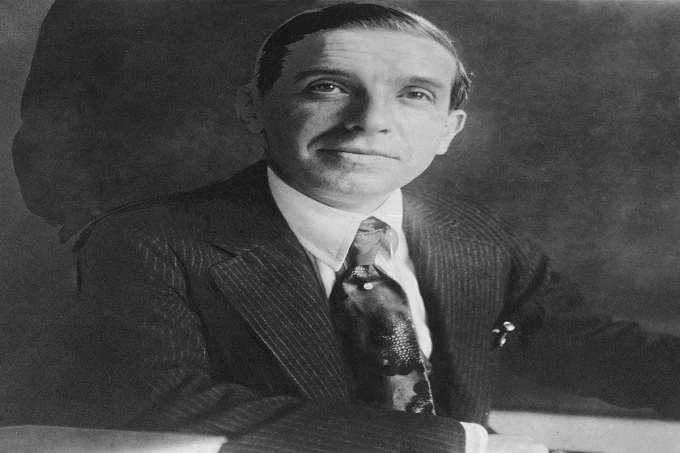

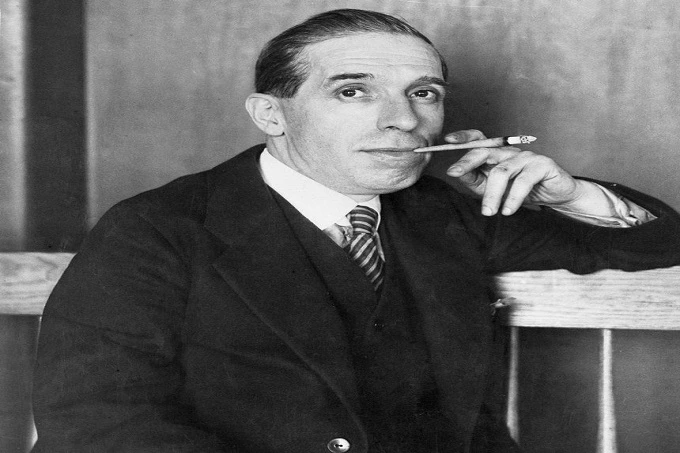

The biography of Charles Ponzi, the son of an honest postman

This man’s life raises many questions: which of the factors – inheritance, destiny, or society – is more responsible for developing our hero’s adventurous personality? According to history, Charles’ grandpa was a representative of the Italian Republic’s court, and his father was a respectable postman. Charles, a baby boy, born in 1882, was a much-loved and desired child. When he was ten years old, his parents used the money they had saved to pay for his education at a prominent public school. Charles Ponzi continued his studies at La Sapienza University in Rome a few years later, with the help of family and friends. However, the family’s beloved soon ran out of money, and Chalz was expelled due to his happy life in the bars.

What was an Italian peasant to do? He didn’t want to return home in shame, so he had no choice but to seek a better life across the ocean. Nevertheless, moving to America was a typical activity among young people from the Iberian Peninsula in the early twentieth century.

He will say that he arrived to conquer the new continent seventeen years later as a billionaire with two dollars in his pocket. He did not, however, board the boat as a peasant. His uncle covered the trip’s expenses and gave his ambitious nephew $200. However, the drive was lengthy and tedious, so Charles decided to revisit the casinos and bars to relieve the stress. By the time he arrived in America, the young guy had a hole in his pocket, as they described it. Because the authorities did not provide any assistance to the newcomer, the young guy was forced to accept whatever work he could find. He eventually obtained stable work at a restaurant where he cleaned and was promoted to waitress. However, his adventurous spirit failed him: he was dishonorably dismissed after many counts of cheating and stealing.

Ponzi was tested for a while before moving to Canada in 1907 and meeting another Italian con man, Zarossi. Zarossi already owned a bank. His clients were powerful and affluent individuals who needed to raise their fortune swiftly. Zarossi offered them investments with a record return of 6%, but the existing depositors’ thirst was satisfied by luring new ones. The bank quickly ‘went bust,’ as one might expect. Charles was compelled to hunt for a new source of income after being left without money and work, but already with a strange concept of enrichment. He couldn’t think of anything better than forging cheques. As a consequence, he received a three-year jail term. Ponzi relocated to the United States after his release.

Former clients from his prior profession remained in touch with him. The adventurer became a smuggler after their instruction. He helped his fellow compatriots who had decided to enter the United States illegally. It’s hardly surprising that he was quickly apprehended and placed on trial again. He was sentenced to two years in jail this time.

In certain groups, his cellmates were well-known figures. Charles Morse was a stock trader and the “Snow King” of New York due to his stranglehold on the ice business. Another of his acquaintances, Ignazio Lupo, became well-known as a Sicilian mafioso who ruled Atlanta. These two men respected young Charles so much that he thought their sentences were overly severe. Ponzi was able to acquire the confidence of the jail officials on his own. Charles’ immaculate handwriting, talent for mathematics, and knowledge of numerous languages helped him advance from laundry worker to jail postal assistant.

Ponzi’s life took a turn for the worst after his freedom. He married Rosa Maria Gnecco in 1918, and in the summer of 1919, he designed the scheme’s mechanism. By coincidence, Charles saw an international return coupon in the mail from Europe. This document permitted him to swap it for stamps, allowing the letter’s addressee to send a free return letter. Because of the difference in currency conversion rates, such a coupon will cost you something different. As a result, Charles developed the plan to purchase coupons in Europe and resell them in America for a higher profit. But it was simply an idea; coupons could only be exchanged for postal stamps in reality. In the early 1920s, Ponzi founded the “Securities Exchange Company.” According to the advertising, a large network of agents from outside the country were buying up, and a profit of 100% in three months was expected. In actuality, no one but Ponzi ever saw these “helpers.” Charles became the largest donor and president of the Boston-based Hanover Trust Bank half a year later. His daily earnings were about a million dollars, which were new depositor investments. Furthermore, investors were not rushing to get their profits; instead, the interest was reinvested “into the company.”

Many people were puzzled by the financier’s extraordinary success. Consequently, journalists launched an inquiry with the help of the public prosecutor’s office. Ponzi maintained his composure until the end, handing out money and serving donuts. His debt to depositors was so large after the formal bankruptcy that the US government continued to pay depositors for another ten years. Ponzi was sentenced to jail.

Charles Ponzi tried land speculation, pretended to die, was deported to his hometown, worked as a guide in Rome and an airline agent, and authored a biography during the following several years. He died in Rio de Janeiro, the dream city of yet another con artist. In a city hospital, he became blind, paralyzed, and died.