Rungholt: A ghost town at the bottom of the sea

In the year 1362, waves from the northern sea engulfed the city of Rungholt, which was located on the coast of that body of water. There are some really peculiar tales told about the people who lived in this submerged town. There are certain gaps in our knowledge about the location of Rungholt. Since a long time ago, people interested in local history and archaeology have been searching for the ruins of a rumored village that was located close to Pellworm Island.

In the year 1882, the well-known German poet Detlev von Liliencron, who at the time was serving as the headman of the agricultural district on the island of Pellworm, had this fever. The poet von Liliencron synthesized all of the piecemeal tales about the submerged Rungholt and its restless spirits, dressing them in poetry lines and enhancing them with his own vivid imagination. This dramatic poetry about a city that was seized by the water ultimately developed the tale of the city that had sunk to the bottom of the ocean.

It is common knowledge that a strange place called Rungholt truly did exist. An ancient document was discovered in the seventies of the 20th century at the State Archives in Hamburg. The contents of the document prove the existence of the Rungeholte parish, which was mentioned in the record. However, throughout the whole history of the Edomshard administrative region, there has never been a city with such a name.

Historians assume that Rungholt was established on the bank of a canal to the southeast of Pellworm somewhere about the year 1200. Rungholt had a population of around one thousand people, most of whom were involved in agriculture. In addition, the town had a small port. It is quite improbable that the locals lived lavishly, and one cannot even speculate about the existence of exceptional riches.

It is conceivable that salt was transported to Rungholt aboard ships during the Middle Ages, when salt was a desirable and pricey commodity.

There is no evidence of lavish funerals or any other indications of the existence of affluent residents in the region that is claimed to be Rungholt, and these discoveries have been made. There were no salt deposits in the area; all that could be found were peat bogs. Despite this, Rungholt was likely of not insignificant significance to all of the people who lived in the Edomshard region specifically because of the harbor.

The residents of Rungholt were caught off guard by the unexpected turmoil. They erected their homes on the bottom sediments in the area where the bed of a deep channel had been during the Ice Age. This practice continued for a few years. The bottom of the dried-up canal slowly lowered, and when it reached its lowest point, the waves from the North Sea began to enter it. In spite of the massive dams that were constructed with an exceptional amount of care and attention, the inhabitants were unable to protect their living location from the ravaging elements. On January 16, 1362, the land on which they had been living was swallowed up by the river, never to be seen again.

The flood is God’s punishment

What caused the deaths of the civilians? Different people on the seashore have various hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. Connoisseurs of these locations are known to have significant conversations among themselves, saying things such as, “All of this is not without purpose – God’s retribution for awful misdeeds!”

An inflated version of the flood that occurred in North Frisia in 1666 was written by Anton Heimreich, who was the author of the North Frisian Chronicle. He conceived of a genuine tale, complete with fascinating particulars and modifications that had been fabricated over the course of approximately 300 years.

In the beginning of Anton Heimreich’s account, he mentions Rungholt as being particularly notable “among all these flooded regions.” According to the author of the chronicle, the prosperity of the region was dependent on this city, and the long-time residents shared many positive memories of the city with the younger generations. Contemporaries of Heimreich were familiar with a variety of tales pertaining to the “underwater metropolis.”

According to the information provided by Heimreich, “one day a priest was summoned to offer communion to a sick individual.” But when this righteous guy entered the room of the sick man, he found a healthy man sitting on the bed, drunk as a pig; it was the blasphemers who intended to make fun of the righteous Christian. He was furious as he ran out of the building, but they would not let him go. They called themselves “godless revelers,” but what they did was physically stop him, take a tin of prosphora that was meant for communion, and fill it with beer.

Following such rebuke, the churchgoer started praying to the Lord, asking him to punish the wicked people who had insulted him. After just a little period of time had elapsed, a severe wind sprang up from the ocean, and tremendous waves rolled onto the shore. Everyone was sucked into the depths of the ocean. The only people the elements did not harm were the priest and two or maybe four virgins. No one else was spared.

When Heimreich was writing his chronicle in the second half of the 17th century, the North Sea had already deposited a substantial layer of silt along the shore in the region that had once been part of the district of Edomshard. Even yet, the tidal region only included the remnants of a relatively small number of previous towns. In certain locations, a layer of sand and silt that was so thick that it prevented the waves from reaching it led to the formation of land again in that location. This time around, individuals were awarded land parcels for a limited period of time. After a period of time, the ocean finally started to cover this area in water. For example, in the last 130 years, the landmass that makes up the island of Südfall has shrunk to a total of just 56 hectares, which is a reduction of three times the original size. When there is a storm of sufficient severity, the whole island is submerged in water.

Depths of the Ocean

It was on Holy Trinity Day in 1921, a lovely spring day, and the year was 1921. Andreas Busch, a farmer from the island of Nordstrand, traveled through the flooded region in a wagon as he was riding through it. Because the horses were stalled up to their bellies in liquid silt, he had already formed the opinion that he would be forced to turn around. The peasant used tremendous effort in order to get the cart that contained the horses to a stable position.

The things that he witnessed later on completely altered his life. The piles that made up the drainage lock-regulator were protruding from the water for a distance of 70 cm directly in front of him. A bit farther out, one could make see the bottom section of the shipyard, and one might make an educated judgment that the area was agricultural land. The water level dropped, revealing the ruins of a medieval town that had been located close to the island of Südfall. Almost immediately, Andreas Busch suspected that it was the illustrious Rungholt.

Before this discovery, no one was sure of the precise location of the spot, the future of which continues to cast a shadow over the thoughts of the people who live on the Frisian islands to this day. Ancient maps show that Rungholt was located to the north of Südfall, but other old maps show that it was located “very” south of this island.

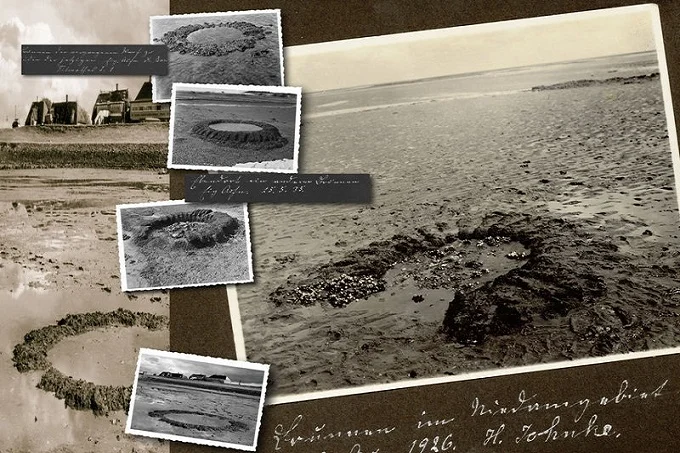

Since he began his endeavor, Andreas Busch has devoted a significant amount of time and energy to conducting an exhaustive search for evidence of Rungholt, which he does with true zeal. He then took his time and carefully inspected, photographed, and mapped the region in great detail while patiently waiting for the tide to recede. The Christian Albrecht University in Kiel bestowed upon the self-educated Bush the prize for scientific distinction in recognition of his archaeological studies conducted at the site of the supposed Rungholt.

If it weren’t for the efforts of the anthropologist Hans-Peter Duerr, the tragic tale of the “underwater metropolis” might have stopped there. It all began when Dürr decided to spend the summer of 1992 on the island of Nordstrand with his wife and their three children. This was the catalyst that set everything in motion. In the summer home, he discovered a map that had been drafted in the year 1652 by Johannes Meyer, a cartographer from Husum (a city in the west of Schleswig-Holstein). Outline of Rungholt and its Parishes was the name of the map’s accompanying legend. Year 1240. Dürr thought back to the famous poem written by Lilienkron, and he made the decision to investigate the problem and tour the region on his own, focusing specifically on the region that Rungholt had shown on the map around the middle of the 17th century.

In June of 1994, a professor from the University of Bremen led a group of his students on a trip to Husum, where they searched for historical items. Professor Duerr started his excavations in the location where Rungholt was shown on the Meyer map. This proved to be a tough task due to the fact that the region depicted on the map is almost devoid of land due to the presence of water and a thick layer of muddy sludge.