Samori Toure’s rise is one of the inspiring examples of resistance in times of the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, which heavily influenced West Africa between the 19th and early 20th centuries.

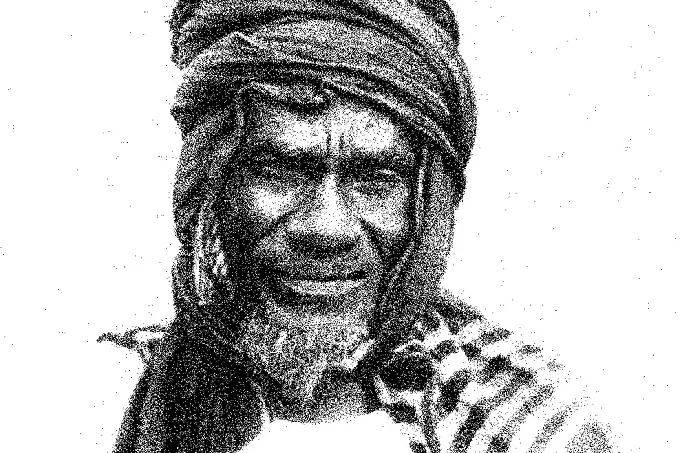

African Napoleon, Samori Toure, founded a Muslim empire in West Africa in the 19th century in order to resist French colonization of the region. With his rise to power during slavery’s heyday, Toure serves as an inspiration for West Africans to oppose the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His father was a merchant, and Toure, who was 15 at the time, followed in his footsteps when he was born in present-day Guinea in the 1830s. These were the years of his trading career that saw him reach out to numerous Islamic experts and implement a version of Islamic finance principles into his business practices.

After the formidable Cisse clan’s head kidnaped his mother in 1853, his life took a dramatic change.

After his mother was kidnapped, he renounced his trade and became a personal slave of the clan’s head so that he might save her. In the end, his mother was freed as a result of her son’s slavery. Learning the Quran and expanding his knowledge of Islamic education, he also gained military training. While serving under the direction of local clan chiefs, he took part in a number of military campaigns.

When Toure returned to his hometown in 1855, he quickly enlisted the help of members of the Camara family. Military training and Islamic education were both given to them by him.

In the years that followed, he rose to the position of military and political supremo in the Milo region. His army’s leadership was dominated by members of his family and close associates.

From the northern Mali city of Bamako to the eastern borders of Sierra Leone, the Ivory Coast, and Liberia, his military skill facilitated his expansion. At that time, he created 162 counties, with his kin at the top of each one.

Officials in the government were given guidance from Islamic experts. During the reign of the Almami, he was elevated to the position of a religious leader of a Muslim empire.

Between 40,000 and 65,000 men were under his command. With the support of former British and French soldiers, he initially imported guns from Sierra Leone and then established a gun factory. King Koroma amassed vast wealth, even capturing gold mines near Sierra Leone’s border with Guinea.

Samori Toure aspired to rebuild the traditional Mali Kingdom, which ruled Western Africa from 1235 to 1670 and whose monarchs and royals were reputed to be affluent and benevolent, as his empire grew.

In the eyes of the public, he was known as a devout Muslim with strong morals. To propagate Islamic knowledge, he sent Quran teachers to nearly every village in his area. He personally observed and tested a large number of Quran pupils, praising those who performed well.

Graduating students from the Islamic school went on to play an important role in promoting the Islamic faith throughout the area. Consequently, Islam flourished swiftly in the late 19th century in Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, when Toure dominated the region.

When French forces battled with his troops in 1881, he responded appropriately. The valor of Toure’s army in repelling the French invasion earned him the name “Napoleon of Africa”.

The French invaded Bamako again two years later, despite his efforts.

Following the Berlin Conference in 1884, French forces began intruding on Mandinka as a result of the division of Africa. French forces could build a powerful assault on Toure’s men with Senegalese troops. Despite his army’s initial success, it was relegated to the interior of West Africa.

In Bure in 1885, Toure’s soldiers wreaked havoc on the French army. The French invasion of West Africa, however, was important, and Toure secured three contracts with the French as a result. His departure from Bure came after he signed the first agreement in 1886; a year later, France took control of Niger’s west bank.

Before leaving the region from Tisinko up to the Niger River, Toure had signed one final agreement with France. France attacked Toure again in 1891, forcing him to surrender much of his kingdom, including his capital, to France.

Due to a mounting French threat against him, he escaped to the northern Ivory Coast regions. France’s Muslim allies were his primary objective during his withdrawal.

He relocated to Liberia in 1898, as Britain refused to furnish him with weaponry in his fight against France. In the city of Kong, Upper Ivory Coast, Toure founded a second empire with a new capital. Sikasso was captured by French forces on May 1, 1898; as a result, Toure and his army set up camp in the Liberian woodlands to stave off a second invasion.

This time, however, his forces were reduced by food and defection, and on September 29, 1898, the French captured Toure. In 1900, he was sent to Ndjole, Gabon, where he died.

Ahmed Sekou Toure, Guinea’s first president, was said to be the great-grandson of Samori Toure. Throughout the African independence movement, Ahmed played a pivotal role.