Serpopards: The mystery of the long-necked Lions

A surprise to all those fascinated by unknown animals was once presented by a pallet (thin stone tile) depicting the pharaoh Narmer. It is one of the first exhibits to appear before visitors to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. This shield-shaped object, 63 cm high, is carved in greenish stone and covered on both sides with bas-reliefs. It is usually dated to the last century of the 4th millennium BC.

The front side shows intertwined long-necked lions (“serpopards”), held on leashes by two bearded men. The image of symmetrically arranged pairs of “tamed” beasts was in all likelihood borrowed from the iconography of the early period of Mesopotamia, possibly from Elam.

Academic scholars, in the absence of other opinions, of course, decided that these images could have had a very specific meaning and symbolized the forcible unification of the two parts of the country.

Here is the story of this artifact by Dr Ian Shaw, who teaches a course in Egyptian archaeology at the University of Liverpool. Beginning in 1985, he excavated various ancient Egyptian ore mines at Khatnoub, Wadi el-Houdi, Wadi Magara, Gebel el-Asre, and other sites:

In 1898, British Egyptologists James Kyubell and Frederick Green found in the ruins of an early palace in the ancient city of Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt a slab of greenish-grayish stone similar to a slate. This find did not make such a furor as the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb 24 years later, but scientists immediately realized the importance of this small object.

Like the Rosetta Stone, this tile, the Narmer Palette, could have extremely important implications for the study of Ancient Egypt. For the next 100 years or so, the content of the palette will be pondered by Egyptologists seeking answers to many questions, from the political origins and preconditions for the Egyptian state to the nature of Egyptian art and writing.

Here’s how Ian Shaw describes the image in the drawing:

“The front depicts intertwined long-necked lions (“serpopards”) held on leashes by two bearded men. The circle formed by the intertwined necks of the serpopards artfully frames a small depression, or plate, for rubbing paint for decorative eye-painting (originally such palettes served precisely for this purpose). But it remains unclear whether such an important ceremonial object as the Narmer’s palette was ever used for a surrendered purpose.”

“On another ceremonial plaque of similar type, a circular depression produces an undesirable effect. Compare, for example, the ‘Palette of the Two Dogs’, also found by Cubell and Green at Hierakonpolis, on which again we see two long-necked lions in the foreground, but the recess is simply between the necks, not created by them (or the ‘Butterfly Palette’ with the recess interrupting the image of a succession of captives)”.

The experts have thoroughly described everything depicted in the palette. Everything there is realistic enough. The serpopards alone, for some reason, “fall out” of reality!

And what if they are real animals, too, especially since they are kept by ordinary earth people – warriors? There are images of the creature on rock drawings, found, by the way, not so far from Egypt, among quite real animals, amazingly similar to helladotherium, the ancestor of giraffe and okapi, which, according to the official doctrine, became extinct about 5 million years ago!

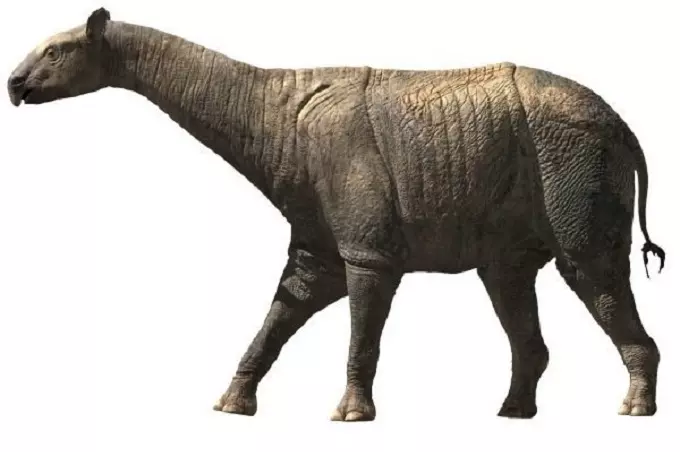

Maybe the pallets show an indricotherium, officially extinct 30-20 million years ago, a relative of the rhinoceros? Remains of indricotherium have been found in many areas of Asia, and Indricotherians had a small head on a long neck and no horns.

Monsters similar to serpopards are referred to by traditional scientists as “chthonic creatures.” In many religions and mythologies, these are creatures that originally represented the wild natural power of the earth, the underworld, etc.

Among the characteristic features of chthonic creatures are usually highlighted beast-like, the presence of supernatural abilities, organically combined with a lack of creative principle, and werewolfism.

In the Slavic tradition, chthonic beings primarily included creepers, which also included animals associated with death and the otherworld. The land itself, in a number of traditions, was represented as a chthonic creature: vegetation – wool, peninsulas – feet, etc.

Chthonic creatures are also associated with marriage symbolism. The marriage of a hero with a chthonic goddess meant mastery of the land (country). Chthonic features have the image of the mother goddess, mythical foremother, also associated with death (chaos).

In contrast to academic scientists, cryptozoologists are trying to explain the appearance of such creatures in works of art through real cases of meetings of ancient people with little-known or unknown representatives of terrestrial fauna, which subsequently disappeared due to human fault.