The brief history of peoples of South Africa

The Zambezi to Victoria Falls and the Angolan border to the mouth of the Cunene River are considered the northern border of South Africa. With the exception of the east coast, all of South Africa is in an arid climate zone. With its belligerent Bantu tribes, this inhospitable region had little appeal to Portuguese sailors, and only with the collapse of the colonial power of Portugal in 1652 did the Dutch establish a fortified settlement, which later grew into the city of Capstadt, now Cape Town.

Free burghers from Holland, French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution, and settlers from Germany began to arrive in the established Cape colony. In their new homeland, they all received the common name of Boers, which means “peasants” in Dutch. They now call themselves Afrikaners, and their language, Afrikaans, is one of the Germanic languages.

The Hottentots

The Boer settlers encountered the Hottentots (historically used to refer to the Khoekhoe) on the coast of the southern tip of Africa, and then, as they advanced inland, the Bushmen and, much later, the Bantu tribes, who had come many centuries ago from the north and were living in far southwestern Africa by the time Europeans arrived.

The Hottentots were warlike pastoralists, culturally far superior to the Bushmen. They lived a patriarchal clan system. The main occupation of the Hottentots was the breeding of cows, bulls, goats, and sheep. The care of livestock was the responsibility of the men. Farming and hunting were of secondary importance in the Hottentot economy. Weapons were spears with iron tips, bows and arrows, and long throwing sticks. The Hottentots made all the necessary iron tools themselves. They worked the iron melted in special pits with the help of fire, stone hammer and stone anvil.

The external life and customs of the Hottentots were described by P. Kolb, a Dutch traveler of the early XVIII century. Their settlements (kraal) were “built in the manner of a circle: in the middle is a large empty square. On this square, they herd their sheep, so that they could not be easily approached. Outside, they place cows, bulls, and other cattle, which should serve as protection equally to men and sheep. In order that the cattle may not be left to themselves and run away of their own accord, they make ropes of certain kinds of reeds, by which they tie the animals in pairs in such a way that… they either have to run together or stay in place.”

The kraals were temporary in nature. As the pastures became exhausted, the population moved to a new place. Among the Hottentots, there was considerable property stratification and social inequality. Captives were turned into slaves.

The Bushmen

To the east of the Hottentots lived a tribe of Bushmen hunters who did not have permanent huts. They took shelter in the bushes at night, where they built temporary huts of twigs. The Boers, therefore, called them “Bushmen”.

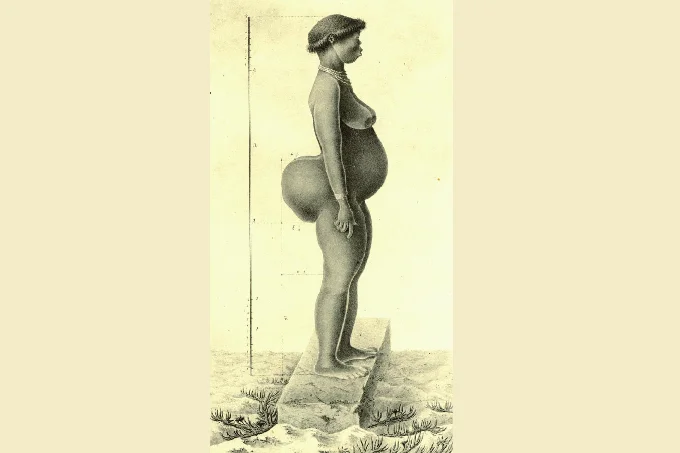

The Bushmen themselves refer to themselves only by their tribal affiliation, without a common name. The Bushmen are a stunted people, although they are somewhat taller than the Pygmies of the Congo Basin. They are characterized by a well-proportioned build, strongly curly hair, arranged in buns. The body is almost devoid of hair. The color of the skin is from yellow to chocolate.

In bourgeois literature, the theory of their North African origin is widespread. It has been recently defended by French scientist A. Breuil and Swiss W. Ellenberger. Their arguments about the similarity in style and subjects of the Bushmen rock art with the North African rock art and about the alleged physical similarity of the Bushmen to the Egyptians of the first dynasties proved to be unconvincing. Linguistic data do not confirm the alleged kinship of the Bushmen and Egyptians.

According to most foreign ethnographers, the Bushmen race has developed in the south of Africa. However, if we pay attention to the “Asian eyelid” of the Bushmen – Epicanthus, the problem of the origin of these people appears to be more complicated.

The material culture and economy of the Bushmen were extremely poor. They did not know metals, cattle breeding and agriculture. They earned their livelihood by gathering and hunting. Their main hunting weapons were a small bow and poisoned arrows with stone tips. Sometimes iron tools (knives, spearheads) were also exchanged from the Hottentots. The only clothing was a loincloth. The Bushmen had almost no domestic utensils. They kept water in ostrich eggshells and were able to make small sacks, baskets, etc. from plant fibers and leather. The material culture at the time of colonization corresponded to the European Mesolithic.

No one in Africa can match the Bushmen in their knowledge of nature. The Bushmen are unsurpassed hunters and artists, connoisseurs of snakes, insects and plants, heirs to a rich folklore. The best dancers and storytellers in all of Africa, they are endowed with an amazing capacity for imitation. One old Bushman was asked how old he was. The answer was: “I am as young as the most beautiful desire of my soul, and as old as all the unfulfilled dreams of my life.”

The social system of the Bushmen is very little studied. They lived by the mother lineage, far from its heyday. The Bushmen had ethnic associations – tribes, but the main socio-economic unit was the local group, like the Australian one, consisting of several paired families headed by an experienced hunter. The best pieces of meat were given to the elders, then to the hunters and their families, and only then to the rest of the herd. The Bushmen’s family customs were characterized by mutual avoidance between son-in-law and mother-in-law, daughter-in-law and father-in-law.

The main place in the religious beliefs of Bushmen was occupied by a fishing cult: an appeal to the sun, the moon, the stars and supernatural beings with entreaties for the granting of success in the field.

Of great interest to modern science are the brightly executed rock drawings of the Bushmen, preserved in the Dragon Mountains. These drawings are a very valuable source for studying the history of the Bushmen. They include depictions of Europeans and scenes of battles between the Bushmen and the Bantoid Zulu and Basuto tribes, as seen in the shields depicted in the drawings. Unfortunately, the authors of these realistic works focused mainly on composition rather than color.

At present, the Bushmen are not engaged in painting and can say almost nothing at all about the drawings of their ancestors. On this basis, it has been suggested that the cave paintings were some other people’s work.

The authentic museum of the art of the Bushmen is the granite mountain Brandberg, located on a basalt base. On the walls of the local caves are depictions of long-eared snakes and other fabulous animals, black figures of dancing people, gazelles and birds, rhinoceros, antelope, ostrich, cheetah, and other animals no longer found in the area.

The images were not made by the hand of a single artist. Over the centuries, the Bushmen have added more and more details to this panorama. Images of red rain have been found, the Skeleton Cave, known for its symbolic depiction of death. A drawing depicts a man holding parts of a human body. A skeleton is drawn next to it. Bushmen never drew landscapes and very rarely drew individual details of a landscape. Ethnographic science knows of no people of Mesolithic time who could compare with the Bushmen and the variety of musical instruments.

The killing of Bushmen

The Boers ruthlessly exterminated the indigenous population, staged arbitrary massacres, and hunted the Bushmen as if they were wild animals. Surviving natives were turned into slaves. A large part of the Hottentots are now employed in agriculture on European farms, as well as in the mining industry in South Africa. There is a mixture of them with the Bantu and white population. Some of the Bushmen retain their traditional way of life, the rest eke out a miserable existence as laborers on agricultural farms.

Having expanded their possessions at the expense of the Bushmen and Hottentots, the Boers faced the Bantu tribes (Kosa, Zulu, Bechuan, Swazi, Mashona, Herero, Ovambo, Ovandonga, etc.), more numerous and developed in comparison with the Bushmen and Hottentots.

The Bantu

The Bantu were able to delay the further advance of the colonists, and the Great Fish River remained the boundary between the Bantu and the Dutch Cape Colony for nearly half a century. But in 1806, England took possession of the Cape Colony, and the Bantu peoples found themselves facing a stronger and more insidious adversary than the Dutch.

Using missionaries, hunters as spies and provocateurs, blackmailing and bribing tribal leaders, sowing enmity among the tribes, and waging wars of extermination, the British colonizers seized the lands of the small Khosa tribes in the mid-19th century and thus advanced the borders of the colonies to the lands of another strong Bantu group, the Zulu. The heroic struggle of the united Zulu tribes for their freedom brought them worldwide fame.

The division of labor was still mainly gender – and age-specific: men and adolescents were engaged in raising cows and bulls, hunting, and making iron and wood products. The women did all the housework, making pottery, mats, etc., on their shoulders, as well as hoeing and gathering. The measure of wealth among the Bantu of South Africa was cattle, sheep, and goats. The Zulu fed mainly on sour milk, vegetables, and corn.

In the pre-colonial era, there was already a tendency to separate craft from agriculture. The Bantu were able to produce fairly pure iron and copper. A few practiced metal smelting and blacksmithing, and they were considered noble members of society. The southeastern Bantu did not know potter’s wheel, but they could make symmetrical vessels, which after firing, were covered with graphite and red ochre, then polished and sometimes ornamented. The Bantu did not know weaving, but achieved excellent skill in processing hides and making clothes from them, vessels to deliver milk from distant pastures.

In a subsistence economy, economic ties were expressed in mutual aid, collective hunting, and intra-tribal exchanges of handicrafts, pottery, wooden utensils, jewelry, weapons, grain, and cattle. There was no money. The inter-tribal exchange between the Bantu tribes, on the one hand, and the Hottentots and Bushmen, on the other, was somewhat more intensive. With the arrival of the Portuguese in Mozambique, the Boers, and the English merchants, with the penetration of buyers of traditional African goods (ivory, for example) and suppliers of European industry, the exchange was given a new impetus.

The people of Zulu

The Zulu clan system was decaying in the early nineteenth century. The clan was strictly exogamous, excluding marriages between its members even to a distant degree of blood kinship, and in some places also totemic, i.e. having its own totem – an animal with which the clan considered itself to be related to a certain degree. The main economic unit of society was the patriarchal family which occupied a separate kraal enclosed by a tall wattle and daub, behind which round-shaped huts were placed in a circle.

The livestock place (in the center) was surrounded by a paling, stone or earthen fence. The tribal chiefs and clan elders were large cattle-owners, and the care of their herds was a heavy-duty for the rank-and-file community members. Consequently, Bantu production relations represented a transition from the cooperative relations of free from exploitation to the relations of dependence and hierarchy. The stable forms and boundaries of the tribes were disappearing, and there was a rapid mixing of the tribes. The disintegration of the tribal structure was an expression of the mismatch between production relations and the nature of the productive forces.

The looming threat of colonial enslavement accelerated the process of merging the Zulu tribes into a nation. The Zulu chiefs Shaka and Dingaan (first half of the 19th century) were able to strengthen the political unity of the Zulu tribes, improve the ancient military organization, and sought to establish friendly relations with the British. The latter oppressed not only the Zulus, but also the Boer colonists.

The Boers decided to leave the Cape Colony in search of new lands. In 1836 they began a spontaneous migration northward, the so-called Boer trek. On the one hand, the resettlement of the Boers was a peculiar form of struggle against British colonial policy, but on the other hand, it was a capture of new Bantu territories, on which the Boers founded the independent Orange Republic.

The conquest of South Africa

The Boer-Zulu War broke out, in which the Boers were supported by the British. In December 1838, their combined forces defeated the Zulu army of Ding’an. The Zulu alliance began to disintegrate. In 1853 the Boer trekkers formed another republic, the Transvaal, on Bechuan lands. The British, in turn, conquered the Basuto, Bechuana, Zulu, Swazi, Mashona, and Matabele in the second half of the 19th century. With the absorption of the independent Boer states at the beginning of the 20th century, almost all of South Africa belonged to England (the northwestern and northeastern areas were taken over by Germany and Portugal, respectively).

In 1910, as a result of collusion between English colonialism and large Boer landowners to exploit and suppress Africans, the Union of South Africa (USA) was created – a dominion of England. Since 1961, it became the independent Republic of South Africa (RSA), which pursues a racist policy of apartheid (Apartheid – separation, separate development) against 20 million Africans, “colored”, and Asians. In this case, it means the policy of racial separation and discrimination).

South Africa’s policy is based on the principles of separating the population on the basis of race, color, or cultural level – as opposed to assimilation. This policy includes measures to implement separation by residence, legal status, territorial segregation, i.e., the reservation of large enough territories for the exclusive use of one group of people (e.g., indigenous territories). Partial apartheid, limited to certain spheres of life, e.g. political, social, and ecclesiastical, is also used. Full apartheid is a detached development in all areas, e.g., with regard to the Bantu. The main purpose of apartheid is to preserve the dominant position of the 2 million “white race” in South Africa.

Despite strong condemnation of apartheid policy as a new type of colonialism in which white oppressors occupy the same territory as the oppressed non-European population, despite numerous Assembly and UN Security Council resolutions on the issue, South Africa’s leaders have made no changes in the principles of racial policy. Aggressive, cultivating extreme forms of imperialist expansionism and exploitation, South Africa’s racist fascist regime is one of the last bastions of history’s doomed colonialism.

The legal status of the remaining territories of South Africa is as follows: Mozambique, Botswana, Zimbabwe are republics; Lesotho and Swaziland are monarchies; Namibia is fighting for independence from the South African occupiers.

Thus, South Africa should be seen as an area of the sharpest social, ethnic, and racial contrasts, an area of massive European colonization. Under the influence of the latter and the rapid development of capitalism, the course of ethnic processes in South Africa acquired a special, deformed character: African tribes of Bushmen and Hottentots were driven into the waterless steppes of the Kalahari, while the Bantu peoples were pushed into reservations.

However, the widespread struggle against oppression and racial discrimination has united the Bantu peoples, who speak closely related languages and share a common underlying culture, mores, and customs. The national liberation movement and the armed struggle against colonialism play an important role in South Africa’s contemporary ethnic processes. This contributes to the mixing of different tribal and local-territorial ethnic groups, the formation of ideas of the national community, and the outlining of national and political communities – future nations.