The mysteries of the palace of Knossos

At the end of the third millennium, around the 17th century BC, the Mediterranean island of Crete was home to a remarkable civilization, traces of which were only revealed at the dawn of the 20th century AD.

On Crete, for the first time in Europe, cities appeared, palaces were built, a written language appeared, and the Cretan State had its own regular army (a fresco showing a detachment of Negro warriors led by a white commander has been found in the palace of Knossos (the Negroes had long inhabited Crete).

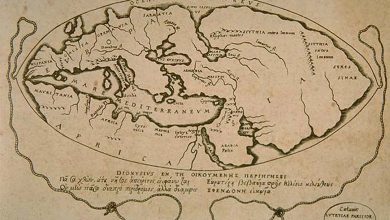

Knossos, located on the northern coast of the island, became the most powerful city where the first stones of the legendary Labyrinth were laid. The whole island was covered with a network of roads leading to the Labyrinth. The Cretan lords had a vast and mighty fleet that protected the island. This alone can explain the absence of fortified walls around the Cretan palaces and cities and the absence of watch-defenses on the coast. The Cretan fleet reigned unchallenged in the Mediterranean Sea, subjugating many lands to the power of the Cretan kings.

The Greek historian Thucydides wrote of Minos: “The rulers of the lands subjugated by him supplied the Cretan fleet with guards at the first request of him”. The Cretan power rose almost to the level of such a colossus of the ancient world as Egypt.

The products of Cretan craftsmen have been found in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, in the Pyrenees, in the north of the Balkan Peninsula, and in Egypt. The fresco in the tomb of one of the courtiers of Pharaoh Thutmose III depicts the solemn arrival of the ambassadors of Crete, and the ancient name of Crete – Keftiu – is often found in Egyptian business papyri.

It would seem that nothing could shake the power of Crete. But at the end of the second millennium BC the catastrophe happened – mysterious, still not fully explained. The cities of Knossos, Phaestos, Agna-Triada, Palekastro, and Gournia are turning into ruins. At the same time, as if in one day, in one instant. Nothing is left of the power accumulated over thousands of years. The empire of Minos was destroyed.

In 1900, Sir Arthur Evans came to Crete to investigate a minor problem with the reading of certain hieroglyphs. One of the greatest archaeologists, a world-famous scientist, an honorary and full member of all kinds of academies and societies, was almost forty years old, but he was already a venerable scholar, a graduate of Oxford, and an expert on ancient Egyptian script.

On his first day on the island, Evans visited the ruins of Knossos. Not far from the ruins, dating back to antiquity, he saw earth mounds that his intuition told him were the remnants of some ancient structures. Evans took up his shovel.

Just a few hours later, the outline of an ancient building appeared in the excavation… And from that moment on, for more than a quarter of a century, he excavated Knossos almost continuously, for he believed and publicly declared that the building he had discovered were the ruins of the legendary Labyrinth! The same one in which lived the monster – half bull, half man – the Minotaur, where King Theseus’ daughter Ariadne led the hero.

Now in any work on the history of Crete, you can see a detailed plan of the “Minotaur Palace”, drawn up as a result of excavations by Evans, his students, and colleagues. From the unfathomable depths of millennia a great civilization rose – so ancient that for the contemporaries of Homer, it was already a thousand-year-old legend. Evans called it the Minoan civilization.

The palace in Knossos has been recognized by all archaeologists as an outstanding monument of highly developed Minoan culture, the residence of the legendary King Minos. The magnificent frescoes on the walls of the palace, the comfortable rooms for bathing, the drainage system, and numerous storerooms allowed to claim that the palace belongs to the “golden Minoan era”, that here, as in a certain antique Paris, once reigned unchallenged joy and carefree.

Almost everyone had become accustomed to these ideas, when suddenly, a German professor of geology at Stuttgart University, Hans Georg Wunderlich, made the claim that the palace of Knossos did not know holidays, that it was instead a place of mourning and sadness. He argues that the palace was a place of the death cult. Here “the remains of the dead were stored, and mummies were prepared”.

He believes that the so-called bathtub of the queen was, in fact, her sarcophagus; that the large painted earthen vessels were not meant for grains and oil, as hitherto thought, but were urns in which the remains of the dead were kept; that the tub-like depressions found in the so-called “store rooms” were really cuvettes in which the dead were removed and prepared for mummification.

The stumbling block that caused Wunderlich to reconsider his ideas about the Palace of Knossos so decisively was plaster, the many details of the Knossos structure were made of plaster. Wunderlich, a geologist, discovered that in this palace, the staircases as well as all the floors of the bathrooms, were made of plaster.

Deeply puzzled by this fact, he could not immediately understand why the Minoans, people who, according to archaeologists, were highly civilized, used gypsum, a soft material easily destroyed by water, in the construction of the palace? Why did they not use marble or limestone instead?

Wunderlich investigated the palace further and discovered many strange things. Why, for example, was there not a single kitchen in the palace of Knossos? Why are the so-called dwellings of King Minos and his queen in a dark basement instead of being on the upper floor, full of light and air? There are no stables attached to the palace and no buildings where chariots should have stood.

Why, finally, are these huge earthen vessels, supposedly intended for grain and oil, so walled up that practically nothing can be gotten out of them?

Wunderlich hypothesized that the ladders were built of soft, pliable plaster because the builders did not expect any brisk traffic on them. The huge amphorae did not serve as storage facilities for supplies, and no one ever lived in the rooms in the basement. Kitchens, stables, and yards for chariots were not needed here, for the palace was not intended for living people.

The palace of Knossos was a palace of death; its rooms were crypts where the bodies of the dead Minoans were preserved. The palace was destroyed by grave robbers.

Of course, Wunderlich’s conclusions were opposed by most archaeologists and cultural historians, although some of them had already suggested that some rooms of the Minos Palace were dungeons and some were places of the sacrifice of the sacred bull, who personified… Zeus himself. Only in the writings of the eminent religious scholar, Mircea Eliade can indications be found that Wunderlich is right.

Eliade found ample evidence that in Crete, in addition to the cult of the bull, the death cult and beliefs associated with the posthumous life of the soul flourished. Zeus was born and died on Crete, and annually the Cretans participated in the mysterious mystery of the “rebirth” of the god.

From every corner of the island, wherever they lived, people set out along the roads to the “Palace of Minos” in Knossos to perform the necessary sacrifices and to take part in the secret and bloody rituals.