The whole truth about Spartacus

Very little is known about Spartacus. No one knows where he was born, who his parents are, how old he was when he died. How he died is also unknown. There is an assumption that he was executed, or maybe he died in battle. But if nothing is known about him, then why has his personality been so interesting for a long time?

Presumably, Spartacus was born in Thrace (modern Bulgaria). Antique authors report conflicting information about his life. According to some sources, he was a prisoner of war, fell into slavery, and was assigned to the gladiatorial school in Capua (City in Italy). According to another version, the Thracian served as a mercenary in the Roman army, then fled and, being captured, was given to the gladiators.

Spartacus was distinguished by physical strength, dexterity, and courage, skillfully wielded weapons. For his abilities, he gained freedom and became a fencing teacher at a gladiatorial school. Spartacus enjoyed great prestige among the gladiators of the Capua school of Lentula Batiak and then among the rebellious slaves of Ancient Rome.

About the physical strength of Spartacus and his mental talents, Plutarch, a Greek philosopher, said that “he was more like an educated Hellene than a barbarian.” “He himself is great in his own strengths of body and soul” – this is how another ancient Roman writer Sallust speaks of the leader of the rebellious slaves.

The greatest slave revolt in the ancient world had the most fertile ground. Wars flooded Italy with slaves of various ethnic groups Gauls, Germans, Thracians, Hellenized inhabitants of Asia and Syria… The bulk of the slaves were employed in agriculture and were in extremely difficult conditions.

Due to their brutal exploitation, the life of the Roman slaves was extremely short-lived. However, this did not particularly disturb the slave owners, since the victorious campaigns of the Roman army ensured an uninterrupted supply of cheap slaves to the slave markets.

Of the city slaves, gladiators were in a special position. Not a single celebration could do without gladiatorial performances in ancient Rome of that era. Well-trained and trained gladiators were released into the arena to kill each other for the joy of thousands of Roman citizens.

There were special schools where physically strong slaves were taught the art of gladiators. One of the most famous schools of gladiators was located in the province of Campania, in the city of Capua.

The uprising of slaves in ancient Rome began with the fact that a group of gladiator slaves (about 70 people) fled from the Capua school after discovering a conspiracy and taking refuge at the summit of Mount Vesuvius.

In total, there were more participants in the conspiracy under the leadership of Spartacus – 200 people, but the guards of the gladiatorial school and the city of Capua defeated the conspirators at the very beginning of their performance. The fugitives have entrenched themselves on the inaccessible mountain peak, turning it into a military camp. Only one narrow path led to it from the valley.

By the beginning of 73 BC. Spartacus’ detachment quickly grew to 10 thousand people. The ranks of the rebellious gladiators were daily replenished by fugitive slaves, gladiators, the ruined peasants of the Campania province, and defectors from the Roman legions. Spartacus sent out small detachments to the surrounding estates, freeing slaves everywhere and taking away weapons and food from the Romans. Soon the whole Campania, with the exception of the cities protected by strong fortress walls, was in the hands of the rebellious slaves.

Soon Spartacus wins a series of convincing victories over the Roman troops, who were trying to suppress the slave uprising in the bud and destroy its participants. The summit of Vesuvius and the approaches to the extinct volcano became the scene of bloody battles. The Roman historian Sallust wrote about Spartacus of those days that he and his fellow gladiators were ready “to die from iron rather than from hunger.”

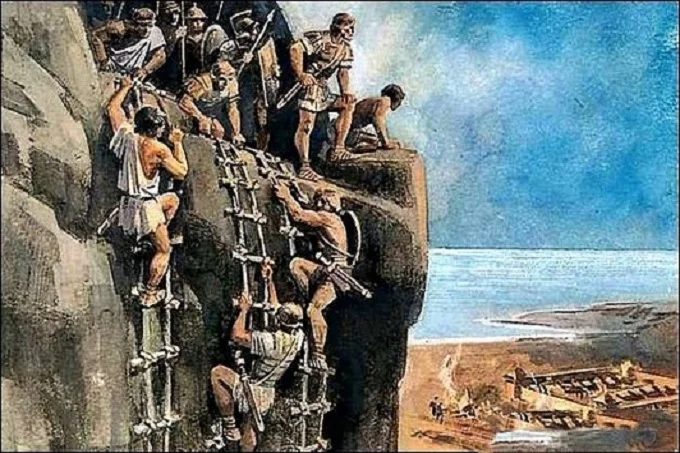

In the fall of 72, the army of the praetor Publius Varinius was completely defeated, and he himself was almost captured, which plunged the authorities of Rome into considerable confusion. And before that, the Spartacists utterly defeated the Roman legion under the command of the praetor Clodius, who presumptuously set up his fortified camp right on the only path that led to the summit of Vesuvius.

Then the gladiators weaved a long staircase from the vine and descended along it from the mountain cliff at night. The Roman legion, suddenly attacked from the rear, was defeated.

Spartacus showed excellent organizational skills, turning the army of rebellious slaves into a well-organized army, modeled on the Roman legions. In addition to the infantry, the Spartacus army had cavalry, scouts, messengers, a small baggage train, which did not burden the troops during their marching life.

Weapons and armor were either captured from the Roman troops or made in the camp of the rebels. The training of troops was established, and also according to Roman models. The teachers of slaves and the Italian poor were former gladiators and fugitive legionnaires, who perfectly wielded various weapons and military formation of the Roman legions.

The army of rebellious slaves was distinguished by high morale and discipline. Initially, commanders of all ranks were chosen from among the most experienced and reliable gladiators and then appointed by Spartacus himself. Management of the Spartacus army was built on a democratic basis and consisted of a council of military leaders and a meeting of soldiers. A firm routine was established for camp and marching life.

Almost nothing is known about the other leaders of the powerful slave uprising in ancient Rome. History has preserved only the names of Kirks(Crixus) and Enomai(Oenamus), two, apparently, Germans, who were elected by the rebellious gladiators as assistants to Spartacus, becoming the commanders of his army.

The first victories of the rebellious slaves met with a wide response. From Campania, the uprising spread to the southern regions of Italy – Apulia, Lucania, Bruttia. By the beginning of 72, Spartacus’ army had grown to 60 thousand people, and during the campaign to the South, it reached, according to various sources, the number of 90-120 thousand people.

The Roman Senate was extremely concerned about the extent of the slave revolt. Two armies were sent against Spartacus, led by experienced and famous victories by the generals – the consuls Gnaeus Lentulus and Lucius Gellius. They hoped to succeed by taking advantage of the disagreements that had begun among the rebels.

A significant part of the slaves wanted to escape from Italy through the Alps in order to find freedom and return to their homeland. Among them was Spartacus himself. However, the Italian poor who joined the slaves did not want this.

In the Spartacus army, there was a split from it, 30 thousand people separated under the command of Crixus. This detachment of rebels (historians to this day argue about their composition – were they Germans or Italians) in the battle of Mount Gargano in Northern Apulia was destroyed by the Romans under the command of the consul Lucius Gellius. If the legionnaires took the rebels prisoner, it was only in order to execute them.

Such a loss greatly weakened the army of Spartacus. However, the leader of the rebellious Roman slaves turned out to be a talented commander. Taking advantage of the disunity of the actions of the advancing armies of the consuls G. Lentula and L. Gellius, he defeated them one by one. A well-organized and trained army of rebel slaves demonstrated their superiority over the Roman legions in every battle.

After two such heavy defeats, the Roman Senate had to draw up troops from distant provinces to Italy hastily. After these two great victories, Spartacus’ army marched along Italy’s Adriatic coast. But even as the Carthaginian commander Hannibal, the leader of the rebellious slaves, did not go to Rome, which was in awe of the real threat of the appearance of a huge army of rebellious slaves and the Italian poor before its walls.

In northern Italy, in the province of Cisalpine Gaul, at the Battle of Mutin (south of the Padus Po) in 72, Spartacus utterly defeated the troops of the proconsul Cassius. From Mutina, the Romans fled to the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is known that Spartacus did not pursue Cassius.

Now the rebellious slaves, who dreamed of finding freedom, were within easy reach of the Alps. Nobody stopped them from crossing the Alps and ending up in Gaul. However, for unknown reasons, the army of the rebels turned back from Mutina and, once again bypassing Rome, went to the South of the Apennine Peninsula, keeping close to the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

The Roman Senate sent a new army against the rebellious slaves, this time 40,000, under the command of the experienced commander Marcus Licinius Crassus, who came from the equestrian class and was distinguished by cruelty in establishing proper order in the army. He receives under his command six Roman legions and auxiliary troops. Crassus’s legions consisted of experienced, war-hardened soldiers.

In the fall of 72, an army of rebellious slaves concentrated on the Bruttian Peninsula of Italy (present-day province of Calabria). They intended to cross the Strait of Messina to the island of Sicily on the ships of Asia Minor Cilician pirates. Most likely, Spartacus decided to raise slaves to revolt in this, one of the richest provinces of Ancient Rome, which was considered one of his granaries. In addition, the history of this Italian region knew many performances of slaves with weapons in their hands, and Spartacus most likely heard about this.

However, the Cilician pirates, fearing to become blood enemies of the powerful Rome, deceived Spartacus, and their naval fleets did not come to the shores of Bruttia, to the port of Regia. There were no ships in the same port city since the rich Roman townspeople, when the rebels approached, left Rhegium on them. Attempts to cross the Strait of Messina on homemade rafts were unsuccessful.

Meanwhile, the army of Marcus Licinius Crassus went into the rear of the rebellious slaves. The legionaries erected a line of typical Roman fortifications at the narrowest point of the Bruttian Peninsula, which cut off Spartacus’s army from the rest of Italy. A moat was dug from sea to sea (about 55 kilometers long, 4.5 meters wide and deep) and poured into a high bank.

As usual, the Roman legions took up positions and prepared to repel the attack of the enemy. There was only one thing left for him – either to endure severe hunger or to storm the strong Roman fortifications at great risk to his life.

Spartacus made their only choice. They launched a sudden night assault on the enemy fortifications, filling up a deep and wide ditch with trees, brushwood, corpses of horses and earth, and broke through to the north. But during the assault on the fortifications, the rebels lost about two-thirds of their army. The Roman legions also suffered heavy losses.

Spartacus, who escaped from the Bruttian trap, quickly replenished the ranks of his army in Lucania and Apulia with freed slaves and the Italian poor, bringing its number to 70 thousand people. In the spring of 71 BC., he intended a surprise attack to seize the main port in southern Italy, in the province of Calabria – Brindisium (today called Brindisi). On the ships captured here, the rebels hoped to freely cross over to Greece, and from there, they could easily reach Thrace, the homeland of Spartacus.

Meanwhile, the Roman Senate sent to the aid of Marcus Licinius Crassus the army of the commander Gnaeus Pompey who had arrived by sea from Spain, which had fought against the Iberian tribes, and a large military detachment under the command of Lucius Lucullus hastily summoned from Thrace. Lucullus’s troops landed in Brindisi, facing directly in front of the Spartacus army. Collectively, these Roman troops outnumbered the rebellious slave army.

Upon learning of this, Spartacus decided to prevent the connection of the Roman armies and break them one by one. However, this task was complicated by the fact that the army of the rebels was once again weakened by internal strife. A large detachment (about 12 thousand people who did not want to leave Italy through Brindisium) separated from him for the second time, which, like the Crixus detachment, was almost completely destroyed by the Romans. This battle took place near Lake Lucan, where Marcus Licinius Crassus was victorious.

Spartacus decisively led his army of about 60 thousand people towards the legions of Crassus, as the most powerful of his opponents. The leader of the rebels seeks to retain the initiative in the war against Rome. In another case, he was expected only by the complete defeat and death of the army he had created. The opponents met in the southern part of the province of Apulia northwest of the city of Trento in 71 BC.

According to some reports, the rebellious slaves, in accordance with all the rules of the Roman military art, decisively attacked the Roman army in its fortified marching camp. The Roman historian Appian wrote: “A great battle took place, extremely fierce, due to the despair that gripped so many people.”

Before the battle, Spartacus, as a military leader, was brought up to a horse. But he, drawing his sword, stabbed him, saying that in case of victory, his soldiers would get many good horses of the Romans, and in case of defeat, he would not need his own. After that, Spartacus led his army against the legions of Licinius Crassus, who also yearned for victory over the “despicable” slaves in Roman society.

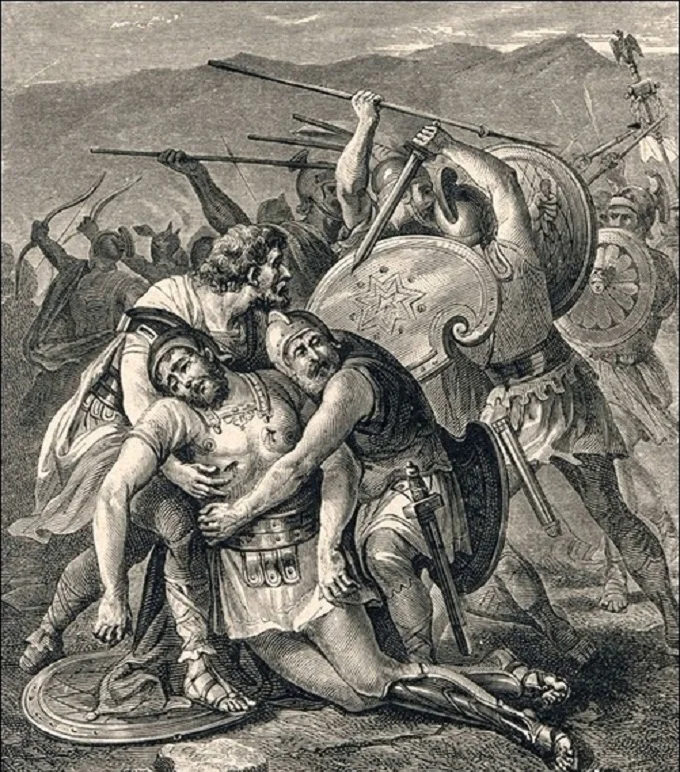

The battle was very fierce, since the defeated did not have to wait for mercy from the victors. Spartacus fought in the forefront of his warriors and tried to break through to Crassus himself in order to fight him.

He killed two centurions and quite a few legionnaires, but “surrounded by a large number of enemies and courageously repelling their blows, he was finally chopped to pieces.” This is how the famous Plutarch described his death. Flor echoes him, “Spartacus, fighting in the first row with amazing courage, died, as would befit only a great commander.”

After staunch and truly heroic resistance, the army of the rebels was defeated, most of its soldiers died a heroic death on the battlefield. The legionnaires did not give life to the wounded slaves and, on the orders of Marcus Licinius Crassus, finished them off on the spot. The victors could not find the body of the deceased Spartacus on the battlefield in order to thereby prolong their triumph.

About 6 thousand rebellious slaves fled from Puglia after the defeat suffered in Northern Italy. But they were met and destroyed by the Spanish legions of Gnaeus Pompey, who, no matter how in a hurry, did not have time for the decisive battle. Therefore, all the laurels of the winner of Spartacus and the salvation of Ancient Rome went to Marcus Licinius Crassus.

However, with the death of Spartacus and the defeat of his army, the uprising of slaves in Ancient Rome did not end. Scattered detachments of rebellious slaves, including those who fought under the banner of Spartacus himself, for several years still operated in a number of regions of Italy, mainly in its south and the Adriatic coast. The local Roman authorities had to make a lot of efforts to completely defeat them.

The victors’ reprisals against the captured rebellious slaves were cruel. Roman legionaries crucified 6 thousand captured Spartacists along the road leading from Rome to the city of Capua, where the gladiatorial school was located, within the walls of which Spartacus and his comrades conspired to free themselves and many other slaves of Ancient Rome.

The uprising of Spartacus deeply shook Ancient Rome and its slave system. It went down in world history as the largest slave uprising of all time. This uprising hastened the transition of state power in Rome from a republican form of government to an imperial one.

The military organization created by Spartacus turned out to be so strong that it could successfully withstand the elite Roman army for a long time. The image of Spartacus is widely reflected in the world of fiction and art.