What is the Bushido code, why did the samurai code of honor play such an important role?

The first thing that comes to mind when it comes to samurai is a master who skillfully wields a sword or a terrible image of a dishonored warrior committing hara-kiri, but little do people ask what is the Bushido code and Why did the samurai code of honor play such an important role?

However, few people think about the fact that behind all of the above lies a much more interesting and deeper meaning that tells about the Way of the Warrior. About what Bushido is, and why the samurai code of honor plays such an important role in culture, as well as other interesting facts about impeccable warriors.

During the early Heian period (794-1185 AD), a northern clan called the Emishi tried to rebel against the then Emperor Kanmu (Kanna). The emperor called on warriors from other clans to help put down the rebellion. After conquering all of Honshu, Kanna gradually began to lose power and prestige, however, he was still revered as a religious figure.

The nobles united politically, eventually supplanting the Bakufu imperial government. The emperor retained ceremonial and religious authority, but the Bakufu held all true political power. They repelled both Mongol invasions, and things went relatively smoothly for the next two hundred years.

From 1467 to 1603, the Daimyo, or feudal lords, fought each other to control the nation, with various commercial support from the Portuguese and Dutch. Tokugawa Leyasu effectively ended this period of war by defeating Ishida Mitsunari at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, solidifying Tokugawa control and establishing peace for the next two hundred and fifty years. The Tokugawa regime completely cut off Japan from the rest of the world, with the exception of a single port in Nagasaki.

In 1854, a show of force by Commodore Matthew Perry in Tokyo Harbor set Japan on a path of modernization, which meant the abolition of the samurai caste and the feudal system in general, and thus the code of honor was born.

Bushido

One of the most comprehensive ways of thinking about Bushido is the Japanese version of the knight’s code of honor. The word “chivalry” comes from the French “chevalier”, meaning “one who has a horse.” Throughout the existence of the samurai, there was no single set of rules that defined Bushido. In fact, neither a formalized set of rules nor the word itself was written down until the Edo period.

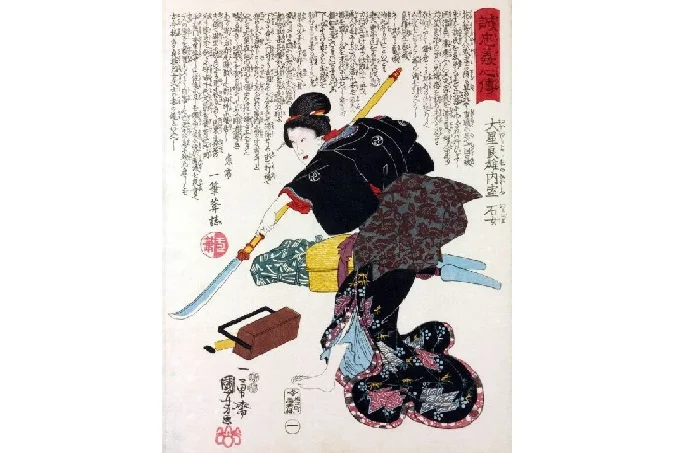

Samurai started out as a caste of soldiers. Thus, the emphasis on conduct was at first exclusively associated with prowess on the battlefield and force of arms. The samurai focused on mounted archery, and their code of conduct was called “Kyuba no Michi”, or “The Way of the Horse and Bow”, which in turn emphasized skill and courage.

During the Heian and Kamakura periods, the method of warfare consisted of duels between single warriors. They announced their names and achievements, challenging any worthy opponent to a fight. The survivor cut off the head of the enemy and presented it as a gift to his general. An element of ancestor worship also existed as a result of Confucian ethics carried over from Tang Chinese culture, but it was less pronounced in the early days of the samurai.

As time passed and the caste gained more and more power and prestige, the code was transformed. Instead of talking about individual prowess, the emphasis shifted to duty to the Daimyo. Warriors were expected to put the interests of their feudal lords above everything else, even their own lives. The custom of individual calls has decreased. Part of the reason for this change was the attempted Mongol invasions.

Martial skill was still important, but it gradually began to give way to more general moral principles, especially during the Edo period, when universal peace reigned, and the samurai were more bureaucrats than warriors. One thing that made the Edo period version different from earlier versions of this code was the emphasis on spirituality, self-improvement, and learning. In Miyamoto Musashi’s famous Book of Five Rings, one of the pieces of advice he gives is to “know the ways of all professions.”

After two hundred and fifty years of peace, the reign of the samurai ended with the Meiji reforms. Many former samurai turned their interests to business and industry. It was similar to the codex of the Edo period. One of the popular sayings of the samurai was “the pen and the sword are one.” In other words, the samurai were expected to be scientists as much as they were soldiers, if not more so, and to practice the arts.

Main rules of the Bushido code

Now let’s move directly to the Bushido code in the Edo period, and consider the main rules of the “Way of the Warrior”:

1. Mercy (Jin)

As warriors, the samurai had power over life and death. They were expected to use this power with discretion. In other words, they were supposed to kill only out of necessity.

2. Honesty (Makoto)

The bushido code required that samurai be absolutely truthful in words and deeds. If promises were made, they had to keep them quickly and exactly.

3. Loyalty (Chuugi)

As already mentioned, putting the interests of the Daimyo ahead of their own was the hallmark of this code of conduct. It is known that some samurai, instead of becoming ronin, committed seppuku after the death of the Daimyo, whom they swore to serve.

4. Reputation (Mayo)

Everything that a samurai said or did affect his reputation and, consequently, the reputation of his Daimyo. He had to be not only a virtuous and reliable servant but also to carefully monitor his appearance, including the care of the sword, even if the weapon was never supposed to be drawn.

5. Courage (Yu)

The Way of the Warrior required unwavering courage, not only in facing the enemy on the battlefield but also in the conviction to act correctly in everyday interactions and make difficult decisions.

6. Respect (Rei)

Respect for others in all situations, even if they were lower in the social ladder, was one of the most far-reaching aspects of the Way of the Warrior. One of the defining aspects of contemporary Japanese culture is the emphasis on respectful interaction.

Myths

It is also worth paying attention to some of the myths that the samurai have acquired, as well as their reputation.

- Myth: The samurai believed that the sword was the only weapon worth fighting with.

Reality: Samurai, at least during the Sengoku period and earlier, had no qualms about using weapons of any kind, even firearms. This idea comes from the paintings and writings of the Edo period, when the samurai carried the katana more as a sign of power than as a weapon.

- Myth: Bushido urged the samurai to never retreat from battle, even if the odds were hopeless.

Reality: One of the works that the samurai studied and imitated was Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. In this book, one of the strategies proposed by an ancient Chinese strategist was to retreat if the battle could not be won.

- Myth: Samurai wanted to die with honor more than anything.

Reality: No well-adjusted person wants to die to the point of actively striving for it. Instead, it was an attitude known as “finding a reason to die.” It was more like identifying a reason for which a person was willing to risk their lives. Serving one’s master was the ultimate goal. Death in this service was considered honorable, but only if it contributed to the goals of the daimyō. The idea of looking for death comes from a misunderstanding of the Hagakure (this is a treatise on Bushido – the samurai code of honor. It proclaims Bushido as the “Way of death”, or “live as if you are already dead.”). The eighteenth-century samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo urged readers to meditate daily and think of all the ways to meet death.

Conclusion

Despite all the advantages of the Bushido code, it has a dark downside. The theme of death pervades many aspects of it, leading to practices that most modern people today would consider morally reprehensible. The custom of seppuku, or ritual suicide by cutting open the abdomen and then decapitation, is widely reported in samurai books.

Needless to say, it was a terrible way to die. The samurai who performed this act was expected to maintain his composure throughout the entire ordeal. Only when the agony became too strong, the second, kaishaku, cut off his torment, and with it his life.

Other macabre customs also existed: the ritual Kiri-sute gomen, or “murder and apology.” If a samurai felt that someone of lower status was not giving him the respect he deserved, he could kill him on the spot. However, after performing the ritual, the samurai was expected to explain the reason, and also required the presence of a witness/witnesses.

If the reason was not weighty enough, like the testimony of a witness, then the samurai could be ordered to commit seppuku. In modern eyes, indiscriminate killing is morally reprehensible and clearly violates Jin virtue, as discussed above. From a more pragmatic point of view, it would be reckless to kill the people responsible for cultivating the land.

Samurai also engaged in duels to demonstrate the superiority of their swordsmanship, which is where the term Tsuji Giri comes from. Another such practice, Tsuji Giri (literally killing at a crossroads), involved testing the point of one’s sword on a defenseless bystander, often at night. This was usually frowned upon, but many samurai did the practice anyway.

Bushido as a moral system flourished during World War II. By that point, it had evolved into a belief in Japanese superiority, absolute submission to the emperor’s will, the idea of no retreat on the battlefield, and extreme contempt for those who surrendered and became prisoners.

No matter how regrettable it may sound, the true “Way of the Warrior” was cruel and sometimes not always fair. Nevertheless, in the eyes of the samurai, Bushido was an invaluable source of inspiration, which many followed without looking back, believing that they were doing the right thing.