How did Africans resist European imperialism?

When they start talking about African resistance to colonization by Europeans, many people remember only the power struggle between whites and blacks (Europeans and Africans). But this is too simple thinking, underestimating the complexity of the problems encountered under colonial rule.

When the Berlin Conference was held in 1884-1885, it negotiated the rules for claiming specific African lands. Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Belgium, and Portugal then began to divide the occupied territories. They began to establish control over the territory of Africa. Colonization had begun decades earlier, and the territory of Angola had been conquered centuries before. The Berlin Conference, however, made colonization more orderly and open.

African resistance began to develop because of Western Europe’s prolonged colonial rule and economic exploitation of other continents. The Europeans acted on the principle of “divide and conquered”. They applied this rule for 400 years in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, as well as in the islands of the Pacific. They waged protracted wars, honing their military prowess and increasing their power.

As they approached Africa to get their hands on the continent’s natural resources, they began to cut into local societies, acquiring allies and intermediaries to help manipulate local chiefs and overthrow the undesirable, often at the hands of the Africans themselves. So resistance to European domination began to emerge in Africa.

But the difficulty was that there was often no peace between local communities either. Nor was there a universally recognized African identity, a unifying people, and a single religion. In what is now Ghana, even before colonization, there was feuding between Fante and Ashanti.

Such complex political relations among the inhabitants of Africa also influenced the nature of resistance to the Europeans. Resistance occurred not only to European soldiers but also to African soldiers. The hierarchy imposed by the colonizers of Western Europe, aided by local proxies, also played an important role in this.

Often the local population was faced with a choice between cooperating or fighting the colonizers. Some tribes tried to limit the control of the Europeans through some friendships with generals and heads of administrations.

Only Ethiopia remained free, successfully defending its lands against invasion by European military and administrations. In 1896, the Ethiopian ruler Menelik II, won a brilliant victory over the Italian army commanded by General Oreste Baratieri and their allies.

Samori Touré, ruler of Wassoulou empire in West Africa in the late nineteenth century, also successfully resisted the French invasion. He became an example of fighting the French occupation. Under his leadership, firearms were produced, and he tried to build diplomatic relations with the French and the British.

At the same time, Samori was pushing the French from their gold mines and trade routes. The Ethiopians fiercely resisted the Italians, rallying around Menelik II. In early nineteenth-century Algeria, Islam became such a unifying factor. The movement of resistance to French colonization was led by Abd al-Qadir.

But in other areas of Africa, the situation was somewhat different. The effectiveness of the resistance was affected by the endless conflicts of local princes. This was successfully exploited by the British. At the end of the 19th century, the territory of modern Zimbabwe was inhabited by tribes at odds with the Ndebele. The British, in every way, warmed up their enmity. As a result, they were able to gain control of Ndebele territory.

Cecil Rhodes fraudulently signed a colonization treaty with the king, who thought the agreement applied only to the diamond mines. The territory is now called Rhodesia.

The British forced the Ndebele to submit by force. The local population began to be used as servants by the colonizers. English soldiers assaulted the honor of local women. All the cattle were taken from the peasants.

The Africans said they would rather die fighting than live in such conditions. The Ndebele began to resist the colonizers. Many British soldiers were killed in the battles. But it was almost impossible to resist the machine-gun Maxim. But under the fierce onslaught of the local population, the British were forced to retreat.

But the British did not accept this situation. They began to infect the natives with smallpox and set the neighboring Mashona tribe against them. The Germans did the same. They played off the Nama and Hereros living in what is now Namibia. But when the Germans took complete control of Nama territory, the tribe united with its former enemy against the colonizers. This was in 1901. The Nama chief, Witbooi, held the Germans responsible for the bloodshed and the war.

After the Namas and Hereros were conquered, the Germans began to exterminate them mercilessly, placing them in concentration camps and starving them to death. Such camps were the forerunners of the Nazi concentration camps. Chief Witbooi was shot and killed during an attack on a German train.

Speaking of the African resistance, the 1929 Igbo women’s uprising – Aba Women Riot – in modern-day southeastern Nigeria cannot be overlooked. At that time, European colonial domination was in the form of pragmatic violence.

The rural women were well organized. They had their own community associations and they rebelled against the impending tax imposed by the local European authorities. This was the only mass uprising of Nigerians before their independence in 1960. The cause of their discontent was the colonial authorities’ census of the population and their livestock. The protests spread throughout the region and were brutally crushed. Fifty unarmed women were killed by British bullets. But this rebellion was not against colonization, but against the local authorities. The women wanted to preserve their political autonomy and preserve their culture. They were trying to break out of the colonial sphere of influence, not to overthrow the colonizers.

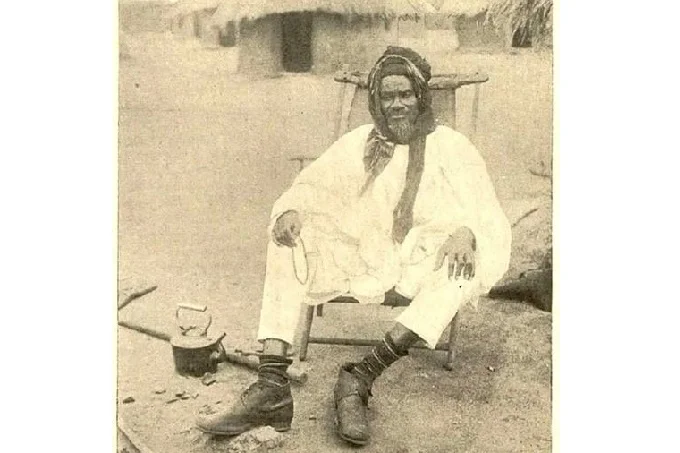

In Senegal, too, there was a struggle against the colonial administrations. Sheik Ahmadou Bamba, a Muslim leader, created the Mouride Brotherhood. He wanted to preserve the ability of the local population to organize itself without colonial pressure. The sheik also defended Islam against Europeans and their culture. At the beginning of the last century, Ahmadou went into exile, but the Senegalese began to heroize him. Eventually, the French government allowed him to return to his homeland.

When World War II ended, political parties began to emerge in the colonial African states. Some of them began to cooperate with European administrations, while others were unwilling to compromise and advocated independence.

The Republic of Guinea was the first to gain independence in 1958. Its president was Sekou Toure. But in some countries, such as Kenya and Zimbabwe, guerrilla warfare began. Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and Namibia also fought for independence. As a result of this bloody struggle, it was possible to get rid of European colonial domination.