How Leander Jameson’s New Year’s raid nearly reshaped map of South Africa

Even in exotic places like South Africa, magical New Year stories sometimes happen. In 1895, a British gentleman chose an unusual way to celebrate the New Year and, with a small detachment, unwittingly attacked a neighboring country. Known as the Jameson Raid, this story of big money, greed, and political ambition has become a colonial mystery still wrestling with experts.

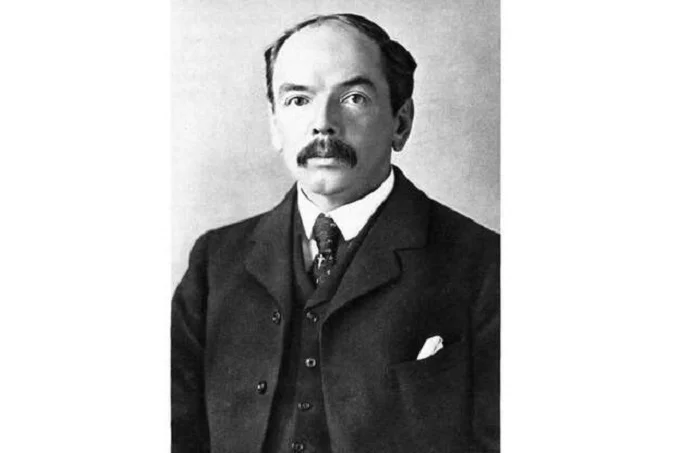

Leander Starr Jameson was a 42-year-old Scotsman who worked as a doctor and then an administrator in the British South Africa Company, owned by the largest South African entrepreneur Cecil Rhodes. Gathering a detachment of volunteers, on December 29, 1895, he announced that he had received letters from compatriots from the Boer Republics of Transvaal, calling for help, and the detachment would go on a campaign to provide it.

When asked if there was an order from the Queen on this score, Jameson replied that the unit would fight “for the dominance of the British flag in South Africa”. Not everyone was satisfied with such a vague answer, and some of the people refused to go. On the morning of December 30, about 500 people spoke from the small border town of Pitsani – Rhodes police corporations and volunteers. The target of the Raid was the city of Johannesburg.

Johannesburg was almost 300 km away, and Jameson wanted to cover that distance as soon as possible. His detachment was completely equestrian, and the convoy was reduced to a minimum. Of the heavy weapons, there were only eight Maxim machine guns and three guns.

Jameson’s squad crossed the border of the Transvaal, and the grueling march began. The detachment marched on December 30 and 31, making only 30-minute periodic stops. People were quickly exhausted and instantly fell asleep on halts, without even thinking about eating. In 70 hours, about 200 km were covered, that is, the average speed of movement was less than 3 km/h – not too fast for a horse detachment.

On the way, Jameson received messages from various officials, alarmed by the news of the Raid. He replied that he did not intend to change his plans, as he was acting “in response to a request for help from the respected inhabitants of Rand in their desire for justice and elementary rights of every citizen of a civilized State.”… As a result, the British authorities disowned Jameson and outlawed him.

Then, two cyclists met with the detachment, who turned out to be the messengers of the very “respected inhabitants of Rand.” They reported that Johannesburg (the city at the foot of the Rand, that is, the Witwatersrand ridge, which gave the name to the area) could not be captured, but Jameson would be met in Krugersdorp on the outskirts of the city. Immediately on New Year’s Eve, Jameson received an unexpected gift – his squad captured the son-in-law of the President of the Transvaal Paul Kruger.

On January 1, at 15:00, Jameson approached Krugersdorp, but instead of his allies, he met armed Boer detachments there. The Boers knew about the Raid from the very beginning, and there is a version that the leader of the raiders was their agent.

The enemy’s awareness left the attackers almost no chance. A battle ensued, which immediately began to take shape, not in favor of Jameson – his machine guns jammed, since there was no water to cool them. Jameson’s men were forced to retreat, regroup, and attempt to outflank the Boer position during the night. Help from Johannesburg never came.

The extremely tired raiders tried to attack again, and when the Boers opened artillery fire, they surrendered. The losses of the detachment amounted to about 50 people, including 18 killed. The Boers left four on the battlefield.

Even for those who were immersed in the twists and turns of South African politics, the Raid looked very strange. At first glance, Jameson not only acted on his own initiative but ignored everything that went against his adventure – be it messages from the British administration or those he intended to save.

In those days, it was really uneasy in Johannesburg, but nothing like an uprising happened. However, the detachment rushed there as if there was a life-and-death fight, and it is unclear whether someone tried to convince the raiders that their help was not required. To understand this story, let’s start from the very beginning.

Diamonds and gold

By the end of the 19th century, Great Britain managed to collect a significant part of South Africa under its flag. As Arthur Conan Doyle wrote, the two independent Boer republics, the Transvaal and Orange, were surrounded by British possessions like a “bone in a peach”. However, the boundaries were rather arbitrary. On both sides of them lived similar people (mostly of Dutch origin), many had relatives and friends abroad. Life was patriarchal and agricultural. The area of the Transvaal was much larger than England, but it had only about 150,000 inhabitants.

Two important events blew up this pastoral world. In the late 1860s, diamonds began to be found in the Orange River valley. In 1873, the city of Kimberley was founded next to the richest deposit. The territory lying beyond the Orange and Vaal rivers was taken over by the British Cape Colony, despite the fact that the two rivers were considered the border. Soon, Cecil Rhodes’ De Beers firm took over the entire Kimberley mine and effectively controlled the global diamond market.

In 1886, an equally fateful discovery took place – it turned out that the Witwatersrand ridge was cut by numerous gold-bearing veins. One of the largest “gold rushes” in history began. Johannesburg grew rapidly near the Witwatersrand (or simply the Rand, that is, the ridge): in 1890, there lived 26,303 people, and in 1896 – already 102,078.

To understand further events, you need to seriously delve into how the gold mining was arranged in the Rand area. The first gold mining companies in Johannesburg worked in an open pit. The simple and cheap method did not require large capital investments and quickly made it possible to make a profit, so the first ten years of Rand’s existence were a time of easy money and the rise of the local rich – Randlords.

A few years later, more detailed geological exploration was carried out, which showed that the local reserves of gold surpassed everything that the most daring minds could think of. The first prospectors were simply picking the tip of the iceberg, and under their feet were about two-thirds of all the world’s proven gold reserves. Gold veins did not stand vertically in the rock but were at an angle to the vertical, becoming more and more gentle with depth – there is a version that they correspond to the channels of ancient mountain rivers. This meant that the open-pit mining companies did not even stake out their fields for themselves. As a rule, they bought out land where gold approached the surface and another area 250-350 m to the south. The veins went much further south, and it was there, to the south, at great depths that the main deposits were located.

This was extremely important information. First, rumors circulated in Johannesburg that Rand was about to run out for a long time. These rumors were put to rest, which made it possible to attract really big business to the development.

Secondly, all areas where open-pit mining could be carried out were already occupied, and large companies began to buy land further south of the original deposits. This is how the second and then the third line of mines appeared. Rand Mines Limited almost entirely owned the second line, and the third line was owned by Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa (CGF). Rhodes owned the latter company.

These industry giants had their own problems. Small open-pit companies started making profits almost immediately and could finance the expansion of production from them. Deep mining was arranged in a completely different way – before reaching the gold-bearing veins and starting to make a profit, it was necessary to invest a lot.

Drilling a mine 250m deep required at least $250,000 to drill. A mine 900 meters deep could cost $650,000. At that time, no one simply invested so much in gold mining – by comparison, the entire Transvaal income from gold mining was approximately 1.2 million dollars. After the construction of the mine was completed, it still needed to be drained – sometimes it took years, rather than months.

It turned out to be a rather contradictory picture. Small firms thrived with an average profitability of 37%. Large companies, no doubt, could also achieve such indicators and turn the Rand mines into real “gold factories”, but so far, they have suffered only losses. In their eyes, the blame for this lay with the government of the Transvaal. Rand Mines Chairman Lionel Phillips said: “I felt that a number of ventures that I and other people were involved in would not pay off – not because we hadn’t invested enough in them, but because we had a bad administration.”

The Transvaal government, then headed by President Paul Kruger, was far from the concerns of the gold miners. The “gold rush” threatened to destroy the usual way of life of the Boers. Diamonds and gold attracted many Outlanders (“foreigners”) – mainly from Great Britain, its dominions, and colonies.

In Johannesburg, 100,000 in 1896, half of the population was white, 15,000 of whom were born in Great Britain, 15,000 in the Cape Colony, 9,000 in other European countries. There were just over 6,000 Boers in the city. By culture, the city was almost entirely English.

The influx of Outlander became a real threat to Boer culture and independence, and Kruger began to take drastic measures. They began to give the right to vote and be elected after 4 years and then after 14 years of residence. Foreign companies began to stifle taxes. Then the Outlander remembered the old English rule – there is no taxation without representation.

In the Folksraat (parliament) of the Transvaal, no one represented their interests, meanwhile, he regularly issued laws that were disadvantageous to the extractive industry. The dynamite monopoly became the fiscal pressure tool. Dynamite accounted for 12-20% of development costs, with the dynamite monopoly having an alternative. Likewise, the government could have imposed a tax on the cyanide needed to extract gold from gold-bearing rock, but it was used primarily by small open pit companies.

Dynamite was just one source of discontent. Food and labor prices were high, and alcohol was not readily available. There was very weak labor discipline in the mines, Monday and Tuesday were tacitly considered “hangover” days, and the custom was not to go to work on these days. Employers resigned themselves to the scarcity of workers. Communication became a separate problem. Two railways ran from Johannesburg: one towards the British Cape Colony, the other towards the Portuguese harbor of Laurenzo Markis. Krueger tried to get the Randlords to use the second line and obstructed the functioning of the first in every possible way. In addition, freight rates were favorable for small companies.

Conspiracy

In a word, big business had many reasons for dissatisfaction with the Boer republic. Historians argue only about the main motive for this discontent. What provoked the conspiracy – business interests or political calculations?

The initiative came from the large gold mining companies in Johannesburg, or, more precisely, from those whom we would now call top managers. In November 1895, Jameson received a letter of complaint of harassment signed by Lionel Phillips (chairman of Rand Mines Ltd), John Hammond (senior engineer at Consolidated Gold Fields), Colonel Francis Rhodes (Cecil Rhodes’ brother and CGF manager), Charles Leonard (attorney, representing the Rand Mines, and a politician speaking on behalf of the Outlander) and a few others.

Cecil Rhodes himself, of course, should have known about this letter. The goldfields of the Transvaal remained his only asset that he did not control politically, and getting the obstinate Boer government out of the way would be a logical step. But Rhodes was not just a greedy capitalist and dreamed of more. As Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, he worked to create a Federation in southern Africa as the dominion of Great Britain. It was planned to link the Rhodes Federation with Cairo by rail and transcontinental telegraph. This was not an empty Manilovism – a customs union had already been created, including the British colonies and the Orange Republic. The Transvaal stood in the way of Mr. Rhodes, too.

But that’s not all. There is speculation that the threads of the conspiracy led to the British government, and they were held in the hands of the Department of Colonial Affairs. London should have been worried about the rapprochement of the Boers with the Germans – there were rumors that German industrialists especially favored Kruger. On January 27, 1895 (on the birthday of Kaiser Wilhelm II), he spoke at a banquet, talking a lot about the loyalty of the German colonists.

One way or another, the alleged scheme, in which local businessmen led by Cecil Rhodes and, possibly, individual British politicians were involved, raises several reservations. First, it is difficult to determine the relative weight of economic and political considerations. Both were too closely intertwined, especially since different interests prevailed among different participants. If Rhodes wanted to see the Union Jack over Johannesburg, then the Randlords needed more business-friendly reforms than a change of nationality. Although the above version appears to be the slimmest, there are contradictions in it. If Rhodes was intriguing, it is strange that the industrialists of Johannesburg were the object of his intrigues and not other ministers of the Cape Colony or politicians in London. It is also strange that he found understanding among the Outlander,

Perhaps all these inconsistencies have one simple explanation: no conspiracy in the end happened, and Jameson acted at his own peril and risk, wanting to push events in the right direction. It is known that there was an agreement that his squad would march between December 28 and January 4. Then something went wrong, and the town of Pitsani, where Jameson’s headquarters was located, began to bombard with messages that everything was being postponed. Perhaps the Outlander could not agree on a flag that they would raise over Johannesburg if successful.

Consequences

One way or another, Jameson met the new year 1896 in the saddle and soon found himself behind bars. Krueger decided to extradite him and the other British to London justice and keep the Outlander leaders for himself. He made it clear that the fate of the latter depends on the calmness and loyalty of the people of Johannesburg. Thus, an uprising in the Transvaal was averted. At the same time, the Ndebele tribe rebelled against the British, since on its territory after the Raid, there were almost no Rhodes policemen left – in today’s Zimbabwe, this uprising is called the first war of independence.

Rhodes lost his post as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, but overall, he and the other participants in the case suffered little. Jameson served a symbolic term in a British prison, becoming a real hero for the nation. In 1904, he himself will be the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and later will become one of the founders of the Union of South Africa. Rhodes’ dream of a federation will come true.

The German Kaiser Wilhelm II, who at that time cherished the plans of war of the European powers against Great Britain, sent a telegram to Kruger: “I express to you my sincere congratulations on the fact that you and your people, without resorting to the help of friendly powers, have succeeded by their own energetic actions against armed bands that invaded your country as peace breakers, and have managed to restore calm and support the country’s independence against external aggression.”

The expression “without resorting to the help of friendly powers” clearly hinted that it would be possible to turn to Germany for such help. Moreover, one of the main consequences of the Jameson raid was a change in public sympathy. Previously, the Outlander could present themselves as victims of arbitrariness and despotism on the part of the Kruger government. After the New Year’s story in 1896, Kruger was already seen in the public eye as the leader of a small but proud nation, opposed to the exorbitant British appetites. Jameson’s Raid helped the Boers to attract support on the eve of the Boer War of 1899-1902. One of the Boer commanders Ian Smuts, recalled: “The Jameson Raid was a real declaration of war… And so, despite the next 4 years of truce… the aggressors consolidated their alliance… the defenders, on the other hand, silently and sternly prepared for the inevitable.”