How the typhus epidemic was defeated in the Warsaw Ghetto

The doctors who found themselves in the Warsaw ghetto successfully stopped the spread of typhus by using the most basic of methods to do so.

During World War II, the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw was the biggest Nazi-era ghettos in Europe. Construction on a wall surrounding the Warsaw area, which Jews mostly inhabited, started in the spring of 1940, after an order from Ludwig Fischer, the governor of the Warsaw district. Nazi leaders claimed that Jews were carriers of contagious diseases and that isolating them would serve to safeguard the non-Jewish population from epidemics when discussing the grounds for establishing ghettos in Polish villages. The epidemic began in the ghetto, where it spread rapidly.

The ghetto has its own horrors

A total of 400,000 people lived in the Warsaw Ghetto, which covered an area of 3.4 square kilometers. The combination of severe overcrowding, terrible living conditions, and starvation produced the perfect environment for the spread of disease to take hold. Typhus broke out in the ghetto in 1941, killing many people.

Typhus is caused by bacteria and rickettsia groups, including the bacterium Rickettsia prowazekii, which is spread through the air. Lice and fleas are the primary transmitters of transmission to humans. The symptoms of typhus include a high fever, chills, rash, and severe muscular pain, among other things. Typhus is a disease that may cause death in around 40% of patients if left untreated.

According to the World Health Organization, a typhus epidemic is more likely to occur when people dwell in large numbers under inadequate living circumstances. The primary factors contributing to the spread of the illness are overcrowding and poor sanitation. Of fact, this was the case in the Warsaw ghetto.

In 1941, the average daily ration for Jews in Warsaw was restricted to 184 calories per person, which eventually decreased to 177 calories per person. There was a scarcity of food and soap, warm clothing, and other necessities. It was impossible for German authorities not to see that the ghetto would quickly become a breeding ground for disease.

Typhoid epidemic

83,000 Jews died in Warsaw between 1940 and 1942 due to hunger and disease. According to records, the typhus epidemic broke out in the ghetto in the first several months of 1941. More than 100 thousand persons were infected, with around 25 thousand dying as a result.

It may seem unbelievable now, but the number of cases started to fall dramatically as early as the end of October 1941, even though the number should have continued to rise. The residents of the ghetto likely saw the turnaround of the epidemic as a miraculous event. There is, however, a highly scientific reason for this phenomenon.

A multidisciplinary, international team of experts applied mathematical modeling to trace the spread of typhus among the ghetto population. According to the models, a growing number of people should have been affected by the epidemic, particularly throughout the autumn and winter months. According to scientists, at the conclusion of the ghetto’s existence, practically every occupant had to deal with typhus. However, something prevented the sickness from spreading.

As a result of the valiant efforts of Jewish doctors to prevent the spread of the illness, experts believe that the models have become more real than they were original.

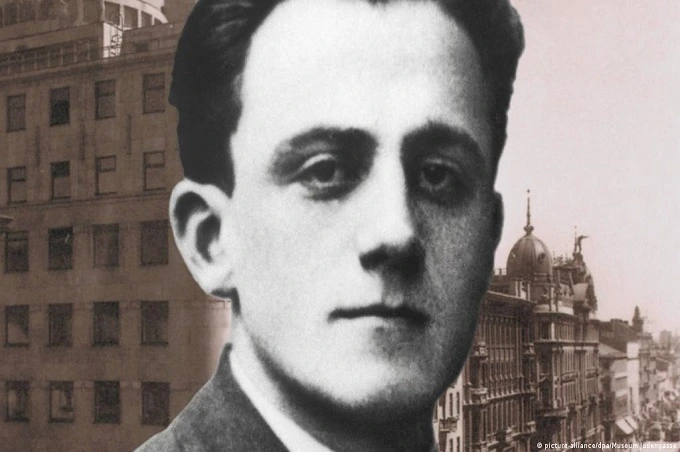

“What surprised me the most was that the typhus epidemic came to a standstill at the very beginning of winter, just when you would expect it to accelerate,” said Lewi Stone, a mathematician and disease modeler from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia and Tel Aviv University in Israel, who founder the study with colleagues from both institutions. “I was convinced for a year that it was most likely simply a corrupted data collection,” the scientist continues. “However, I went to Ringelblum’s journal, which had detailed descriptions of everyday life in the ghetto.”

The Polish historian Emanuel Ringelblum ended up in the ghetto with his family in the fall of 1940. He kept records of the life of the ghetto, which, among other things, preserved data on the number of cases of typhus. According to Ringelblum, the number of cases was reduced by 40% by autumn.

Doctors have accomplished a remarkable achievement

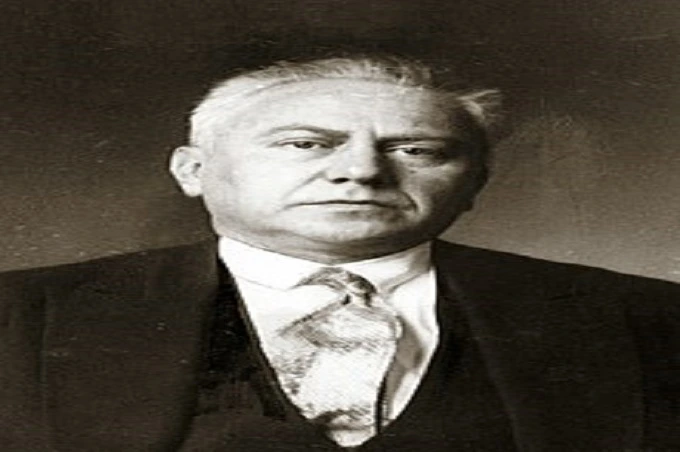

In the Warsaw ghetto, there were a huge number of skilled doctors. Ludwik Hirszfeld, an immunologist, hematologist, and infectious disease expert, was one of those who worked on the project (he is known for establishing the existence of genetic patterns in the inheritance of blood groups). The National Institute of Hygiene, which operated in Warsaw during the First and Second World Wars, was founded by Hirszfeld, who was also a founding member. Once in the ghetto, he continued to work on public health problems.

Typhus is a constant companion of war and starvation. This illness claims the lives of more people than even the “most brilliant” military leader. “This is often the deciding factor in the outcome of conflicts,” Hirszfeld says in his memoirs. In 1942, he could make his way out of the ghetto.

Hirszfeld and other doctors arranged hundreds of public talks intended to increase awareness among the residents of the ghetto about the reasons for the disease’s spread. Hirszfeld and other doctors were among the first to recognize the disease’s spread. They also trained young medical students in private, according to reports.

Recent scientific research has shown that the anti-epidemiological measures made by doctors in the ghetto were responsible for the decrease in cases. Moreover, although nowadays tetracyclines are used to cure typhus (the first representative of this class of antibiotics was found only in 1945), they were, in reality, the only accessible methods of treating the disease in the Warsaw ghetto, where disinsection and hygiene were the only options.