Is it possible to resurrect extinct animals?

From the Ice Age, do you remember Manny the woolly mammoth and Diego the saber-toothed tiger? Wouldn’t it be amazing to witness such extinct animals in person? Science fiction may soon become a reality thanks to recent developments in biotechnology and a fascinating process known as re-creation or resurrection.

What is the definition of de-extinction?

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines it as the production of functionally comparable replacements for extinct species that are not perfect replicas of the original lost species.

De-extinction may be done in three ways:

- Reverse breeding: current species with characteristics in common with ancient species may be found and selectively bred to create offspring that look more like extinct species.

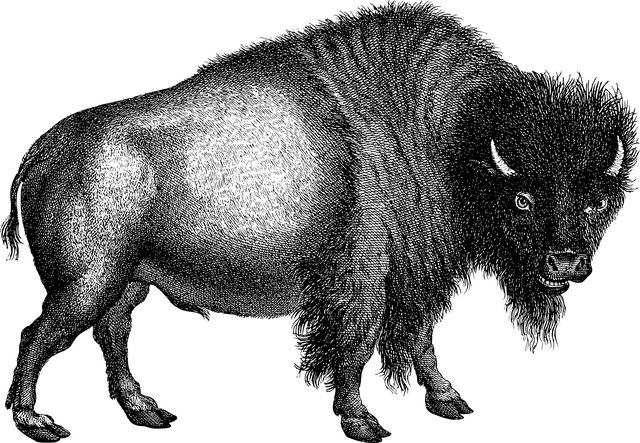

The Tauros Program, for example, is bringing back the extinct bison, the progenitor of all contemporary cattle. The scientists seek to generate an animal that closely resembles the original wild bison in Europe by breeding existing cattle genetically related to bison. In comparison to other, more intricate de-extinction procedures, this is a rather rudimentary approach.

- Cloning: this is precisely what everyone hears the most. The nucleus holding the extinct animal’s DNA is extracted from its surviving cells to make an extinct animal clone. This DNA is then placed into an egg (obtained from the animal’s closest living cousin) that lacks its DNA, i.e., the nucleus. When this egg cell matures in the womb of a surrogate mother, the baby will be genetically similar to the extinct species.

Because this approach needs well-preserved cells with complete nuclei, it is only applicable to creatures on the edge of extinction or who have just gone extinct. In 2003, for example, this strategy was employed to reintroduce the bucardo (Pyrenean ibex), a wild goat found in Europe’s Pyrenees mountain region. The cloned animal barely had a 10-minute life span. Due to a huge hard additional lobe in one of the lungs, the children could not breathe. The bucardo, unfortunately, was the first mammal to go extinct twice. However, this is the most successful cloning so far.

- Genetic engineering: owing to improvements in current technology, this is the most recent approach that has become accessible. It utilizes gene-editing methods such as CRISPR to replace genes in its closest living cousin with those from extinct creatures. The hybrid genome is then implanted into the surrogate.

The Woolly Mammoth Revival Project aims to find critical genes that help woolly mammoths adapt to the freezing tundra environment. These genes can be put into the Asian elephant’s genome after they’ve been discovered. They are hoping to create a hybrid cell with primary elephant DNA and a few mammoth genes. Consequently, rather than an exact mammoth duplicate, the outcome will be a hybrid elephant that has been genetically manipulated to look like a mammoth.

Why bother resurrecting extinct animals in the first place?

The revival of extinct creatures in Jurassic Park is a flawed concept. Dinosaurs, thankfully, are no longer a threat since their DNA has finally degraded 65 million years after their demise. Under some unusual situations, DNA may persist for a few million years at most. But, if we could resurrect extinct creatures during this period, should we?

Because all creatures play important roles in their ecosystems, the emptiness created by their death may be disastrous. Woolly mammoths, for example, were superb gardeners. They disseminated plant seeds over the Arctic meadows with their nutrient-rich excrement. Their extinction has resulted in biodiversity and the conversion of meadows into cold, mossy tundra.

Ecologists from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) established criteria in 2016 for determining which species should be resurrected to have the most influence on earth’s ecosystems. Species that were recently extinct, biologically unusual, and could be reintroduced in large numbers were chosen.

The Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), the Reunion gigantic turtle (Cylindraspis indica), and the lesser stick-nest rat(Leporillus apicalis) all satisfied all three requirements.No projects for the rebirth of these species, however, have commenced.

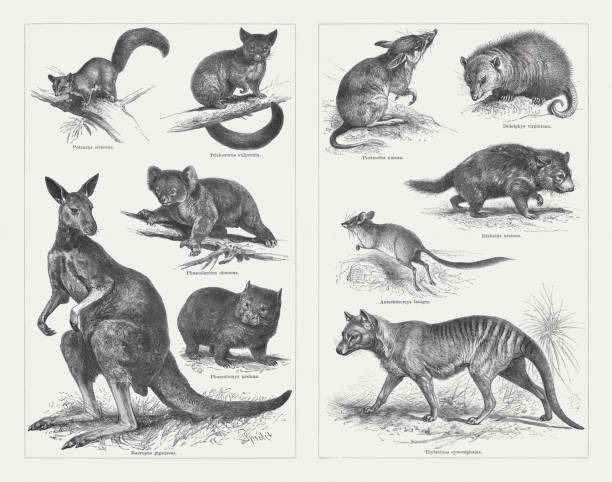

De-extinction is a fantastic chance to make up for previous errors. Humans play God, causing the demise of many of these creatures due to hunting, pollution, and habitat damage. The passenger pigeon, for example, previously roamed North America, but a youngster shot down the last wild passenger pigeon with a toy machine gun about 1900. The Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) was a carnivorous marsupial endemic to Tasmania, New Guinea, and Australia that became extinct in 1936 owing to habitat degradation, a lack of prey, and hunting. The Pyrenean ibex (bucardo) was a European ibex that roamed the globe for thousands of years until being hunted out by hunters in 1999.

Opponents contend that, since revived creatures will never be 100 percent identical to extinct originals, the environmental harm created by humans is not eliminated when extinct species are resurrected.

Others worry that by the time we succeed in resurrecting one species, the earth will have lost a thousand more. Proponents of de-extinction continue to push the concept as a solution to the planet’s continuing catastrophic extinction. Many specialists say that we must first and foremost safeguard the remaining animals.

Bison, quagga (Equus quagga quagga), giant tortoise from Floreana island, passenger pigeon, woolly mammoth, heath hen(Tympanuchus cupido), and an attempt to restore various types of moa(order Dinornithiformes) are currently active extinction eradication projects worldwide. If all goes according to plan, we could have another chance to see them again.