The best period for explorers of all kinds was arguably the turn of the 20th century. Although technology has come a long way, many parts of the world still have not yet been explored. Of course, it wasn’t about entire continents like it was during the time of Columbus, but there were still a lot of mysteries in the vast regions of Africa, South America, and the Himalayas. In the meantime, affluent tourists of the 20th century already had portable cameras, small mapping apparatus, and, more crucially, highly developed medical. The remaining “white patches” were erased in just a couple of decades as the researchers achieved mobility, survival, and autonomy.

A desert-like Sahara appears to be the worst possible environment for a person. However, commerce caravans always passed through it. Never before as it is now, taking such a route will be simple, but it will still be dangerous. The Amazonian selva is even more unwelcoming for human life despite the abundance of rain and flora. Because you can’t see much behind the trees and no transit will just travel through these forests, charting it is still challenging. There are hundreds of amazing ways to pass away there; therefore, this is where we need to be. In the bush, there are undoubtedly great secrets and many treasures.

Who started the habit of looking for lost cities?

The commander of the Bandeirantes, or “hunters of the Indians,” was a Portuguese officer whose name was unknown. These were actual tomb robbers, finders of abandoned mines, and lovers of various forms of gain, typical for the middle of the XVIII century. But these people had the guts to go where no European had yet set foot, and they undoubtedly ran the risk of losing their lives because, in that scenario, rescue would certainly not arrive.

A diary called “Manuscript 512” came from one of these Bandeirantes and is currently kept in Rio de Janeiro’s National Library. The original is extremely difficult to access; however, a scanned copy and a separate English translation have been made available online. The paper is frayed, and the text has many omissions from preservation in multiple archives, but the overall message and some interesting details have been retained.

The Portuguese detachment travelled throughout South America for ten years looking for silver mines until they discovered an abandoned settlement on a mountain in 1753. Although it appears to have been abandoned for a while, a manufactured stone-paved road is said to have led to it. After stopping out of caution, the travellers decided to wait until dusk to determine whether the city was truly empty. The lack of fires and smoke will serve as proof of this. The detachment entered the city the following day without using the triple arch. An empty square with two-story stone homes lining its edges greeted them. There were no traces of previous occupants’ homes inside, such as furniture or other household belongings.

A black column with a statue of a man pointing north with his hand stood in the middle of the square. The manuscript’s author passed his look to the stated spot and noticed a bas-relief of a young guy wearing a laurel wreath. The once-grand structure, which now lies in ruins like much of the city, looks to have been a ruler’s palace or a temple of some sort. While reporting that poultry and geese are roaming freely, the author concludes that an earthquake must have caused the destruction. The city was probably abandoned very recently, yet nature has already started to take back its former position. The group came to a large, deserted building some distance from the city; it was made up of 15 small rooms and one huge hall. The researchers discovered gold and silver traces as they travelled downstream of the river, along with an entire coin of unknown origin.

The diary’s remaining pages are so extensively damaged that only isolated phrase fragments are left on them. Although they appear to be white, it appears that the detachment encountered members of a local tribe who were “shaggy and wild.” This is pretty weird. The Bandeirantes returned to the Portuguese fortification, from which the manuscript’s author sent a message to a prominent figure in Rio de Janeiro. Since the author explicitly implies that he will only tell the recipient directly about the location of the ruins and mines, recalling how much he owes him, the message’s nature suggests an informal relationship. Actually, this concludes the tale of the city that was lost, found, and then once more forgotten in a jungle. It will be recalled when Manuscript 512 reappears in the archives, and the hunt for the lost towns begins almost a century later.

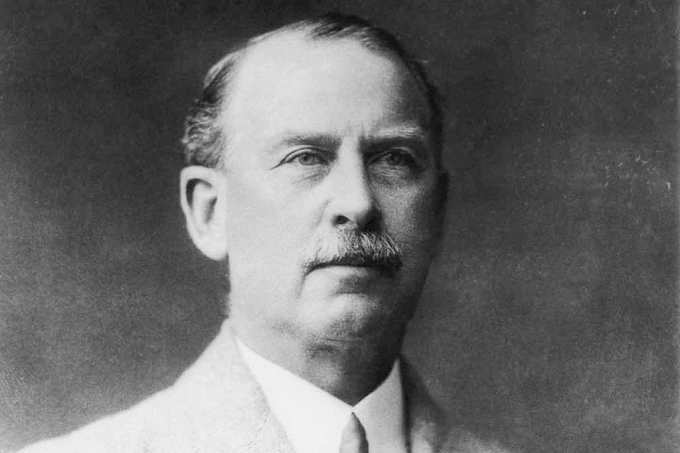

Percy Fawcett and the Lost City of Z

From 1886, Percy Fawcett served in the artillery troops and later worked for British intelligence in North Africa, where he mastered the profession of a topographer. His father was a member of the Royal Geographical Society, and Fawcett was friends with the writers Rider Haggard and Arthur Conan Doyle. When writing the novel The Lost World, the latter will be inspired by Percy’s stories about his expeditions in South America.

With such an introductory fate that seems predetermined, office work certainly could not satisfy the passion for travel and discovery. So in 1906, on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society, Percy Fawcett came to La Paz to map the border between Bolivia and Brazil. It is enough to look at a modern map to appreciate the complexity of the task; this is an almost impenetrable jungle, where even today, there are practically no roads from Bolivia.

The next nine years were spent travelling through the jungle. In 1907, Percy reported that he had personally shot a 19-meter-long anaconda, for which biologists ridiculed him. In addition, he reported on other animals unknown to science, such as small cat dogs and giant spiders, capable of fatally poisoning a person. Fawcett also wrote about double-nosed dogs, for which he was criticized, but today we know the two-nosed Andean Tiger Hound, which does seem to have two noses.

Percy was distinguished from most other European pioneers by his friendliness towards the locals, who reciprocated, shared their folklore, appointed guides and supplied provisions. In 1911, Fawcett retired from the army and, no longer burdened by anything, again went to the Amazon to scout hundreds of kilometres of jungle, now not only for mapping but also in search of the lost city “Z”.

It is unknown what influenced Percy so much – whether the stories of the locals or rumours about the “Manuscript 512”, but from that moment on, the idea of the “Z” will never leave the traveller’s mind. The concept of “Z” was much broader than a single city. Fawcett was sure that an advanced civilization once existed in the depths of the Brazilian jungle; accordingly, there should be many remains and traces. In the researcher’s mind, the city described in Manuscript 512 occupied the modest place of “one of”, along with Paititi and El dorado.

Then the First World War began, and even though he was already 50 years old, Percy Fawcett returned to Britain to go to the front. He commanded an artillery brigade, participated in the Battle of the Somme and was awarded the Order of Distinguished Service. The war is over, Britain has emerged victorious, and Percy has returned to the Amazon, which seems to be his true home.

In 1924, with the support of a London group of financiers known as”Glove”, Percy Fawcett, along with his son Jack and several other companions, went on a decisive assault on “Z”. The instruction Percy had left was of an exemplary nature, saying that in case of failure if the expedition did not return, no one should go in search of them, because the rescuers would suffer the same fate. There was no reason not to trust Fawcett Senior, given his formidable experience as a trailblazer. On May 29, 1925, Percy sent his last letter to his wife, where he announced that he was preparing to set foot in uncharted territory.

It is known that the expedition crossed the Xingu, a southeastern tributary of the Amazon, and the message was generally positive. Two years later, the Royal Geographical Society declared the expedition was missing.

Since then, many attempts have been made to find traces of Fawcett. In 1933, his compass was found near the possessions of the Bakairi Indians, but they did not report anything definite. A 1951 expedition found bones that belonged to a European, but it soon became clear that they could not be Percy. In 1996, the search group was captured by the local Kalapalo tribe, but there were no casualties; everyone was released in exchange for uniforms and weapons.

One way or another, nothing but rumours could be found today. The most mundane versions say that Fawcett’s expedition was too small to survive in such harsh conditions, and Indians or wild animals killed them. There is a more exotic version where Percy goes insane and joins a tribe of cannibals. Some alternatives manage to connect the disappearance of the researcher even with the hypothesis of a hollow Earth, where Percy Fawcett still found a lost civilization.

Science changed its mind

At the end of the 2000s, archaeologists had a terrific tool at their disposal. LIDAR laser technology allows you to see the soil relief through the foliage of trees. Aeroplanes and drones equipped with such Lidars rushed to the Amazon and found a whole complex of relatively small villages connected by an extensive network of roads. Usually, these sections are rounded, located at a distance of 2-5 kilometres from each other and have three roads connecting them. Following the aerial observers, the usual archaeologists arrived in the jungle to work on the ground. They found the remains of terraces and channels, and many earthen hills turned out to be overgrown and already destroyed by pyramids, religious platforms and squares.

Excavations in these conditions are complicated, so the laser vision of aircraft is far ahead of the shovels of diggers. According to the most daring estimates, the found network of settlements can also have quite large cities in the past with a population of several tens of thousands of people, which was considered completely unthinkable 10-15 years ago. Lost cities like the golden El Dorado may not have existed, but Percy Fawcett believed so much the lost civilization did indeed exist.

However, other questions remain: what kind of civilization was it, to what level did it develop, and when did it decline? Probably, by the beginning of the 20th century, it no longer existed, and Fawcett’s search was doomed to failure. However, it is quite possible that Manuscript 512 is still not pure fiction but describes the real experience of a nameless Bandeirante.