The Scientific attempts to solve the mystery of the Shroud of Turin

One of the most mysterious religious relics – the Shroud of Turin – has haunted scientists since its inception. This is a unique phenomenon in the context of Christian teaching and from a scientific point of view – after all, this is one of the few material evidence of the existence of Jesus Christ.

In that case, of course, if the shroud was, in fact, his burial shroud and not a fake of a later era. Therefore, at the moment, there are a vast number of attempts to prove or scientifically disprove its authenticity.

For a believer to doubt the shroud’s authenticity is blasphemy; for a learned doubt, it is the only way to get to the bottom of the truth. Therefore, attempts to comprehend irrational facts continue to this day rationally. For the first time, they started talking about the shroud in the Middle Ages, swindlers, taking advantage of the gullibility of believers, tried to cash in on it. Pieces of Noah’s ark, hairs from his beard, more than 40 shrouds were provided as sacred relics – and as a result, all these items turned out to be faked.

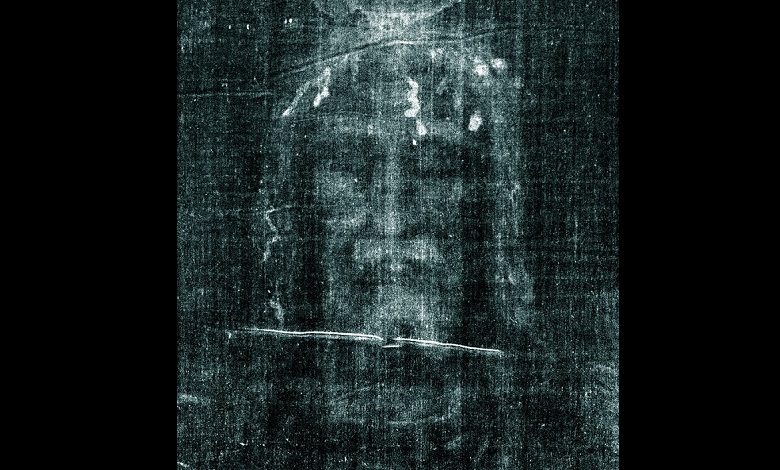

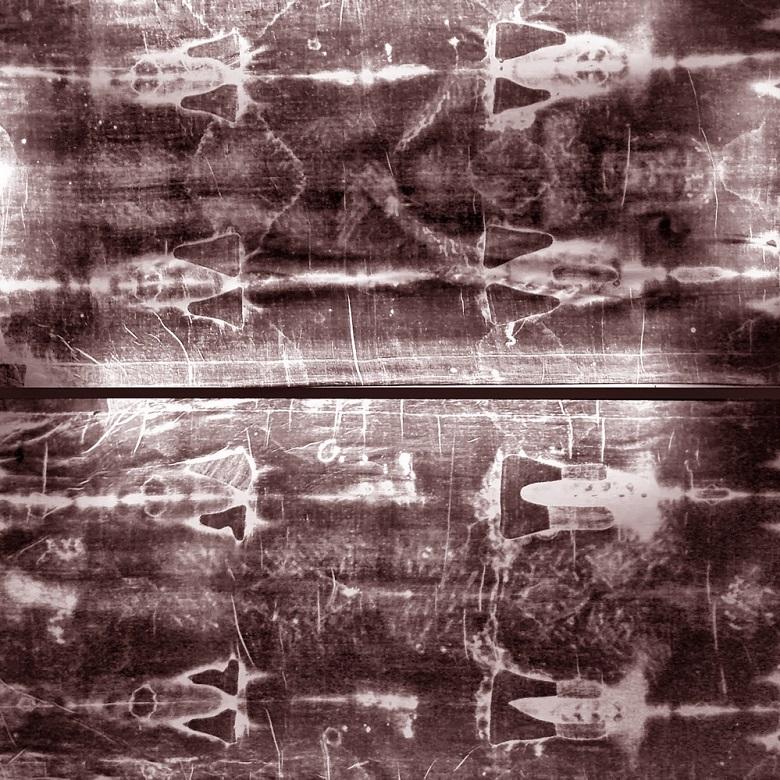

The Shroud of Turin is a long piece of linen kept in a silver ark above the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, in northern Italy. In the centre of the canvas, brownish spots appear, which merge into the image of a lying man.

In photographs, the image appears more clearly, especially on negatives – the fact is that it is negative: darkened areas, for example, the eye sockets, look light on it, and vice versa. How did this unusual “photo” get on the fabric and, most importantly, when?

For more than 400 years, the shroud has been kept in Turin; it was in France before that. Until the XIV century. The history of this relic remains a mystery. To establish its exact age, scientists have resorted to spore-pollen analysis. It turned out that the pollen from the shroud belongs to plants growing in Italy, France, Turkey and Palestine. And the most fantastic thing is that seven specimens of pollen of salt-loving plants were found, which are found in the Dead Sea region – where Christ was crucified.

In addition to the printed image of a person, traces of blood were found on the shroud. Their study under X-rays and ultraviolet rays confirmed that it was indeed blood. Spectral analysis showed the presence of iron, potassium, chlorine and traces of haemoglobin.

On photomicrographs and under a microscope, traces of blood appear natural – that is as if brown or red clots had recently been left behind. Chemical analysis found that the blood belongs to a man.

Studies have shown that the shroud is not a drawing since almost no colouring pigments are found. And if the image were applied with oil, it would saturate the fabric. The shroud’s material belongs to the era of antiquity by the nature of the weaving of threads, which was proved by the radiocarbon method.

In 1976, for the first time, a computerized three-dimensional image of a person was obtained following the footprints on the shroud. In 1988, it was allowed to cut three shreds from the cover for research at the universities of Zurich, Arizona and Oxford. All three laboratories were unanimous: radiochronological analysis dates the age of the tissue to the 13th-14th centuries. But infrared spectroscopy refuted the results of these studies.

In addition to the methods of the exact sciences, the methodology of the humanities was also used. Interpretation of the texts of the canonical gospels and apocryphal makes it possible to establish that almost all texts mention the shroud, which was wrapped around the body of Christ. That is, the shroud existed. Art critics also draw attention to the striking similarity of the appearance on the shroud with the traditional image of the face of Christ, which from the VI century.

It became unified on the icons: an elongated face, a straight nose, a beard, deep eye sockets, a broad forehead, until the VI century. Jesus was portrayed in different ways. There is a version according to which the Turin Shroud was first discovered in this century. In addition, medieval sources mention just such a face of Christ on the shroud.

The traces of bleeding wounds are not on the palms, as is customary in the iconographic tradition, but on the wrists, which corresponds to ancient Roman customs, cast doubt on the shroud’s falsity. If the image on the shroud were copied from the icons and not vice versa, then the wounds would probably be in the area of the palms.