Mesopotamian gods

Not only were the earliest civilizations rich in culture and invention, but they were also rich in various beliefs, some of which have persisted to the present day. On the other hand, Mesopotamia was and is still shrouded in mystery, even though much is known about the gods of Egypt, Scandinavia, and Greece. Further in the article, we will discuss the gods that people from various cultures, including the Sumerians and Babylonians, believed in.

Nabu

Nabu is the Babylonian god of education and knowledge. He is the son of Marduk and the grandson of the god Enki (Ea). His name, which translates to “the herald,” refers to his prophetic abilities and writing talent. Nabu was the god of scribes and was in charge of protecting the Tablets of Destiny, which established who had the right to rule over everything in the universe (alternately called Anu, Enlil or Marduk, and later Ashur). In some depictions, he is shown holding a stele; in others, he is shown riding or standing next to the dragon Sirrush. At the Cradle of Civilization time, the god Nabu was regarded as one of the most significant and revered deities. Therefore, the great Babylonian festival known as Akitu, celebrated in honor of all the gods and included thanksgiving for the harvest could not have taken place if he had not been present. He has been worshipped for millennia, and he was one of the few gods whose statues and temples survived the fall of the Assyrian empire in 612 B.C. when invading armies stole them from many gods. In addition, he is frequently contrasted with figures from other ancient cultures, such as Thoth from the Egyptians, Apollo from the Greeks, and Mercury from the Romans.

Adapa

In Sumerian and Babylonian mythology, Adapa is the first man to be created. He is the son of Ea (or Enki) and is depicted as being furious over the sinking of his boat. As a result of his anger, the wings of the South Wind are broken, and Adapa is forced to travel to heaven to atone for Anu. Since Ea wanted people to continue to live mortal lives despite her knowledge that Anu would offer Adapa the food of immortality, she cautioned him not to consume any food or drink while he was in the land of the gods because of doing so would result in his death. Adapa follows Ea’s recommendation and turns down the food and drink offered to him; as a result, he is tricked out of his opportunity at immortality. He was the first of the seven ancient sages known as the Abgal.

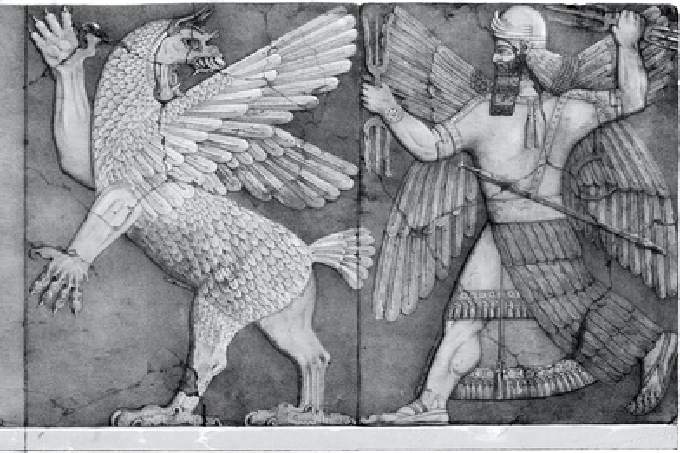

Anzu

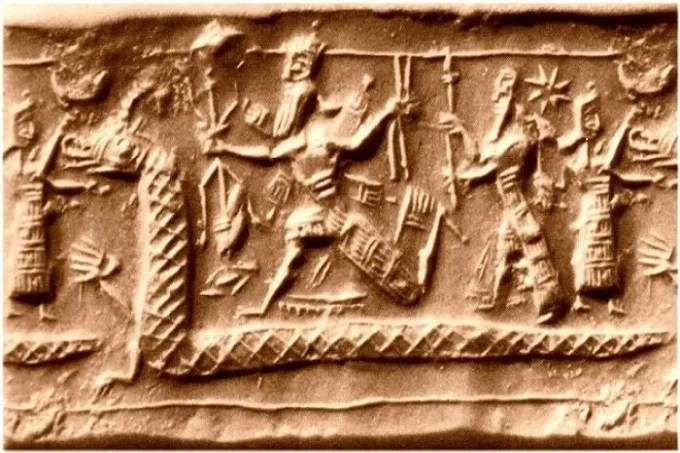

Anzu is a divine celestial being that appears in Babylonian, Sumerian, and Akkadian mythology. He is depicted as a gigantic bird with the head of a lion and is also known by the names dZû and Imdugud. In one telling, Anzu was said to have the ability to breathe fire and be so enormous that the movement of his wings could cause massive storms. The Sumerian superstar of the Huluppu tree includes the Anzu bird as one of the creatures that lived in Inanna’s tree. This legend gives the Anzu bird a prominent role in the story. In one version of the tale, he was given the responsibility of protecting the Tablets of Destiny, which were the documents that provided support for the supreme god’s right to rule. However, the god Ninurta was responsible for Anzu’s death and took the Tablets with him when he left.

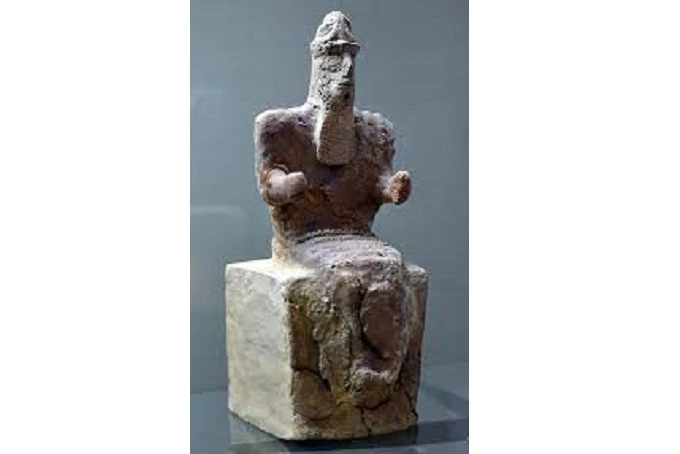

Assur

Assur is also referred to as Ashur, and in Akkadian, it is written as Anshar. The most important god in the religion of the ancient Assyrians, Ashur’s gods, dates back to the city’s earliest days. He was worshipped as the Assyrian god of heaven and war and was given the title “Lord of All Heaven.” His name in Akkadian means “all the sky,” and the Assyrian kings frequently relied on him as a powerful ally. His name comes from the Akkadian language. He is frequently depicted as an archer wearing feathers who is drawing a bow while sitting atop a serpent or dragon. A significant portion of his mythology and iconography, such as the dragon serpent of Marduk or his wife Ninlil, is taken from works originally composed in Sumerian or Babylonian.

Abgal

In Sumerian mythology, the Abgal are seven sages sent to earth by Enki at the beginning of time to impart to people the sacred self (laws) of civilization. They were also known as Abgal by the Akkadians and Babylonians, who depicted them with a fish body and human head or a fish torso and human arms, sometimes with or without wings. According to Babylonian mythology, Abgal can also take the form of griffins or appear as men adorned with wings. For cleanliness, Abgal people always have a bucket and a horn of incense on their person. By name, they were Adapa (the first man) Uan-dugga, En-me-duga, En-me-galanna, En-me-buluga, An-enlilda and Utu-abzu.

Bull of Heaven

The Bull of Heaven, also referred to as Gugalanna, was the ruler of the underworld and served as the consort of Ereshkigal, the Queen of the underworld. The Bull of Heaven was under the control of the Lord of Heaven, Anu. Ishtar, who Gilgamesh snubbed, demands Anu in the Epic of Gilgamesh to let the Bull of Heavenloose on Gilgamesh’s kingdom so that it may wreak havoc there as a retaliation. Enkidu is sentenced to death for his role in the murder of the Heavenly Bull, which he and Gilgamesh committed together. After the death of her husband, the goddess of heaven is depicted in the poem “The Descent of Inanna” as making the journey into the underworld to console her sister, Ereshkigal. The latter is mourning the loss of her husband.

Anu

In the stories written before 2500 B.C., the god of heaven and Lord of Heaven was called Anu, also known as An in the Sumerian pantheon. Antu was his wife, and their union resulted in the birth of the Annunaki, who served as judges of the dead. The Sumerian word “Anu” can be translated as “sky,” and the Sumerians associated it with the sound of thunder rolling across the heavens. In times of severe weather, he was depicted as a colossal bull braying above the clouds. Over time, Anu rose to the position of the supreme lord, becoming the source of all power that the other gods used. Only his son Enlil was able to communicate with him. The people prayed to the lesser gods, who then relayed their requests to Enlil. Before Enlil received them, the Tablets of Destiny were initially possessed by Anu, who then passed them on to Enlil.

Ea

The Babylonian god of wisdom and freshwater was known as Ea (Enki). He was the god of magic who triumphed over his father, Abzu, and was responsible for the creation of the earth. Ea was one of the Mesopotamian pantheon’s most revered and influential gods. He plays a pivotal role in the narrative of the Great Flood, where he saves humanity by advising the righteous man Atrahasis to build an ark before the water comes, and in the well-known story of the “Descent of Inanna,” where he provides the means to rescue the goddess from the underworld.

Enlil

The Sumerian god Enlil was associated with the elements of wind and air, and his name translates to “Lord of the Air Elements.” He was significantly more powerful than any simple deity of an element, and Ninlil served as his consort. Enlil, An, and Enki were the members of a triad responsible for the governance of Heaven, Earth, and the Underworld, or the heavens, the sky, the atmosphere, and the earth. Enlil was a significant weather god who was frequently worshipped and prayed to in the ancient Egyptian religion in the hopes of having favourable weather conditions and a successful harvest. He was the ruler of the Sumerian pantheon after 2500 BC and was worshipped by the Akkadians from 2334 to 2083 B.C. He possessed the Tablets of Destiny and was the ruler of the Sumerian pantheon. During Hammurabi’s reign, the god Marduk devoured and made him a part of himself. Despite this, Ellil is depicted in several myths as the most important god and ruler of the divine beings. Even though the centre of the cult’s worship was located in Nippur, he was revered throughout Mesopotamia.

Ereshkigal

Ereshkigal was a Sumerian goddess of the underworld and Queen of the Dead. Her name means “Lady of the Great place,” and she was considered to rule over the realm of the dead. She was a powerful and terrifying goddess, and her consort was the Bull of heaven before Enkidu ended his life. She was the older sister of the goddess Inanna, whom she killed when she came to visit her in the underworld at the funeral of Bull of heaven because she believed that Inanna was responsible for the death of Heavenly Bull. However, as a result of Enki’s craftiness, she was forced to bring Inanna back to the world of the living. Ereshkigal ruled the land of the dead alone until the arrival of the god Nergal, who quickly became her consort and was known to the Mesopotamians as the “Land of No Return,” a dark and gloomy place. She was also referred to by the name Irkalla. Stories about Ereshkigal, such as “The Marriage of Ereshkigal and Nergal” or “The Descent of Inanna,” have similarities to later Egyptian myths, such as “Osiris and Isis,” and Greek myths, such as “Demeter and Persephone,” in the motif of the Dying and Reborn God, which is most well-known from the story of Jesus Christ.

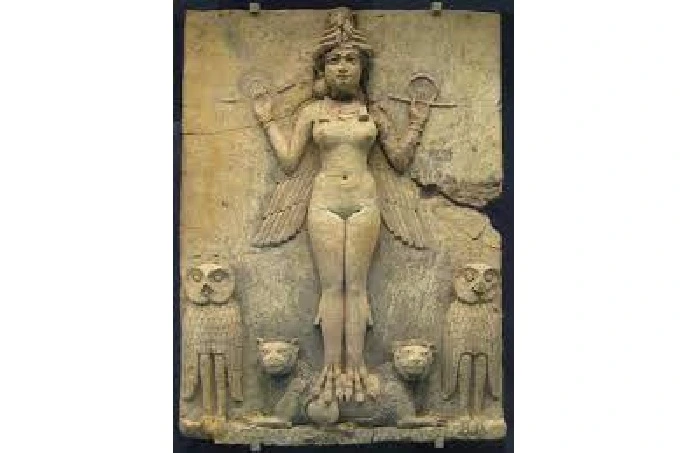

Inanna

The Assyrians called her Ishtar, but the Sumerians referred to her as Inanna. She was the goddess of passion, fertility, love, prostitution, and war. She came to be closely associated with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, who, over time, came to assume many of her characteristics. Inanna, the most well-known and revered deity in the entire Sumerian pantheon, is depicted in a prominent role in many well-known stories, myths, and hymns of Sumer. She is also one of the seven significant deities of early Sumer, along with Anu, Enlil, and others. Enheduanna, Sargon of Akkad’s daughter, was the Chief Priestess of Inanna in Uruk and the author of many hymns and songs dedicated to her. Sargon of Akkad, also known as Sargon the Great, invoked Inanna for protection and victory in battle and guidance in politics. She is frequently depicted sitting atop a lion and is referred to as the “Queen of Heaven.” Her older sister’s name was Ereshkigal when she was alive. It is said that she gave the city of Uruk her sacred self (laws), which were given to her amid a drunken feast by the god Enki. She was the primary goddess and the patroness of the city of Uruk. As the goddess had a close relationship with the planet Venus, she is frequently portrayed in works of art that are dedicated to her as being very free. In the Etana Myth, she is referred to as Inanna, and she was initially thought of as the twin sister of the sun god Utu (Shamash).

Marduk

Marduk, the hero-god of Babylonia, is considered the king of the gods. He is credited with defeating Tiamat and the forces of chaos to establish order in the universe, an order that required the cooperation of both gods and humans to preserve. He is the god of justice, compassion, regeneration, magic, and healing. He is also the god of justice. In addition, he was famous for settling disputes between the gods, and as a result, he was sometimes referred to as the “Shepherd of the Gods.” In the epic of “Irra,” the character Marduk gives Nergal control of the city of Babylon, but upon his arrival, Nergal is so enraged that he destroys the city. Marduk is one of the most popular and enduring Mesopotamian gods, and the Assyrians saw him as the son of their supreme god Assur.

Tiamat

Tiamat, who takes the form of a dragon, is the primordial mother goddess of Mesopotamia. She is also known as the goddess who gave birth to the gods and is the consort of Apsu. Marduk was victorious in the conflict and ended her life as a result. After she passes away, the rivers Tigris and Euphrates emerge from her eyes. Her story can be found in the Enuma Elish, a Babylonian creation myth. Tiamat was portrayed as salt water, and Apsu was portrayed as fresh water; the union of these two gods gave birth to all of the other gods.

Tiamat created eleven terrifying beasts with the dual purpose of exacting revenge for Apsu’s death and wiping out the other gods. Marduk was able to defeat all eleven of the creatures that Tiamat had created, and as a memento of his victory, he left images of them in the water that was left behind in Absu. The people who lived in Mesopotamia were put to extensive use as part of magical incantations and as a means of defence against evil and the forces of chaos. Many of their portraits have survived to the present day in the form of statues placed outside of palaces and temples, the most famous of which is the Ishtar Gate in Babylon.