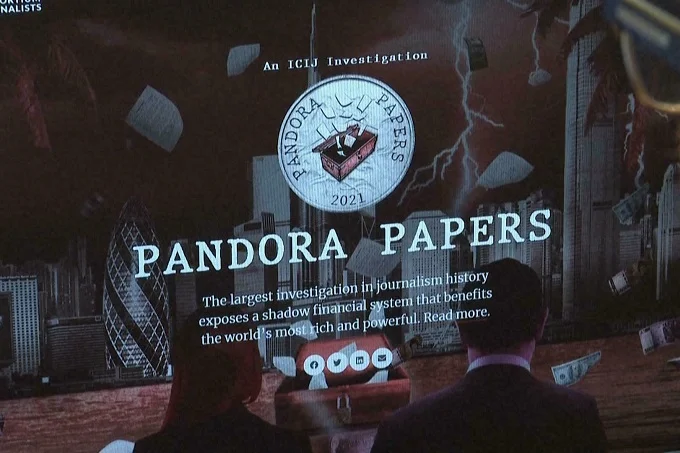

Pandora papers in Africa: offshore finance and the arrogance of power

The Pandora Papers investigation is one of the most outstanding efforts ever made to unmask the mechanisms behind the world of offshore finance. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is unprecedented, with 11.9 million files obtained from 14 of the most important offshore service agencies and investigated by over 600 journalists.

By “offshore”, literally “off the coast”, in economics, we mean all those countries where laws are in force that allow you to receive favorable tax treatment, usually protected by very strong guarantees of secrecy and anonymity. By extension, with “offshore finance” we refer to the complex of techniques and regulations with which capital is moved to these areas by establishing companies located in the so-called tax havens, in a more or less lawful and predatory way.

The Pandora Papers have highlighted how, never before, the global political and economic elites have the tools, techniques, and covers that allow them to evade national taxation and hide their capital. What is impressive is the degree of refinement of these instruments and the size and ramification of offshore finance.

Suffice it to say that the survey covered thousands of the most prominent figures in business, entertainment, and politics (including thirty-five heads of state) from virtually all over the world.

Offshore finance has long been a known phenomenon, especially after the similar Panama Papers scandal, but this survey highlighted how the size and functioning of this sector seriously threaten national economies.

Africa has been affected by these revelations in two ways. First of all, as many as fifty-three African journalists took part in the investigation, but above all, the documents that emerged involved dozens and dozens of politicians, entrepreneurs, and influential personalities of the continent.

From the reports, it appears that the African continent is perfectly integrated into the global offshore economy. However, this figure is not new, given the role played by African countries in the global economy precisely in the years in which this underground sector was formed.

Since the 1980s, a long series of changes in the global economy has allowed the financialization of the international economy, leading to the development of the complex system on which offshore exists today. At the same time, Africa suffered its first debt crisis and the consequent Structural Adjustment Plans (SAP) of the International Financial Institutions (IFI).

These draconian measures have meant that accompanying the financialization of African economies and their entry onto the global stage were wild deregulation, instability, and unclear boundaries between public and private spheres.

This chaos has generated the optimal conditions thanks to which many economic elites of the continent have been able to assume a hegemonic and predatory position in the economic system of their countries, causing inequalities among the African population to grow dramatically.

In the meantime, this situation allowed the same people to come into contact with the international offshore galaxy. The enormous capital, obtained by plundering the continent, flowed into tax havens.

Despite the perfect integration of African elites into the geography of the offshore, the position of Africa nevertheless remains peculiar. In fact, the continent lacks important tax havens, with the exception of Seychelles and Mauritius which, however, play a secondary role in the system. Therefore almost all of the capitals involved in these trades leave Africa in favor of other areas of the world.

African political, legal, and financial institutions are, in fact, considered too fragile and unreliable by international elites who are therefore less inclined to choose African countries as a place to hide their fortunes, despite many of these offering tax advantages that are difficult to match.

There fore, the system that emerged from the Pandora Papers seems to relegate Africa to a subordinate position within the geography of offshore finance. Once integrated into the system, in fact, Africa is entitled to all the evils and little or none of the advantages of the supply chain, even in a case like this where it is questionable whether there are actually any advantages for the community.

Who appears in the Pandora Papers?

The number of African politicians involved in the scandal is forty-three, of which ten are Nigerians, nine Angolans, and the remainder are from Morocco, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Chad, Gabon, Republic of Congo, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

Among the prominent personalities overwhelmed by the investigation are three presidents: Denis Sassou-Nguesso (Republic of Congo), Uhuru Kenyatta (Kenya), and Ali Bongo (Gabon). These must be added great magnates of the continent’s economy, particularly linked to the business of oil and other resources.

According to some analysts, the primary intent of powerful Africans in hiding their fortunes is not to avoid taxation. In fact, in many countries of the continent, taxation is generally very low concerning large assets, if at all. The main objective of their actions is rather to obtain privacy and secrecy regarding their tax positions and protection from the seizure of these assets in the event of legal troubles.

Therefore, the general picture that emerges is very clear: African elites are perfectly integrated into the so-called “global rich and powerful” circuits and have the same means and the same access to offshore financial services as their counterparts in other parts of the world.

Of many of the powers involved in the scandal, it is interesting to note that there have been rumors of their assets hidden abroad for years. In fact, there is a certain cynicism towards the behavior of political elites among the African population, which therefore does not expect that such a scandal could generate changes in the conduct of these subjects or a change in the continent’s financial regulations. This could result in a further de-legitimization of the status quo in the eyes of the population, especially the younger ones, with effects that are difficult to predict.

According to OECD estimates, the African continent would lose at least fifty billion dollars every year in tax avoidance, offshore investments, money laundering, and other forms of capital diversion. In fact, some data from the Global Financial Integrity think-tank show how the illicit movement of capital could be worth on average between 7.5% and 11.6% of the entire value of trade in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Obviously, the impact of this phenomenon differs from country to country, but it seems to affect them all, albeit in different forms, with the most worrying situations in oil-producing countries such as Nigeria and Angola.

The analysis of the Pandora Papers has highlighted even more how a direct correlation exists in many African countries that link the entry of capital through international cooperation and foreign investment to the flight of capital to tax havens. From this detail, it emerges even more clearly how the bottlenecks in the mechanisms of wealth distribution are the points where some predatory elites manage to appropriate enormous fortunes, which are immediately diverted offshore.

A money hemorrhage of this magnitude cannot fail to have concrete effects, which directly impact the lives of millions of Africans. The lack of taxation on these capitals translates into much tighter budgets for the administrations of African countries, which in turn means less education, infrastructure, and welfare services.

Furthermore, once they enter the offshore economy, the large capitals that leave Africa do not return there except in the context of investment projects that aim to generate a profit which in turn will take the route of tax havens. Already scarce resources available to national welfare programs, therefore, risk becoming even scarcer in the long run as more and more money is used to generate private profit rather than social impact.

In Africa as elsewhere, therefore, the problem is that every dollar that sinks into offshore finance represents wealth stolen from the community in favor of a privileged minority and which will therefore stop generating value for the community to instead fund the selfish interest of very few.