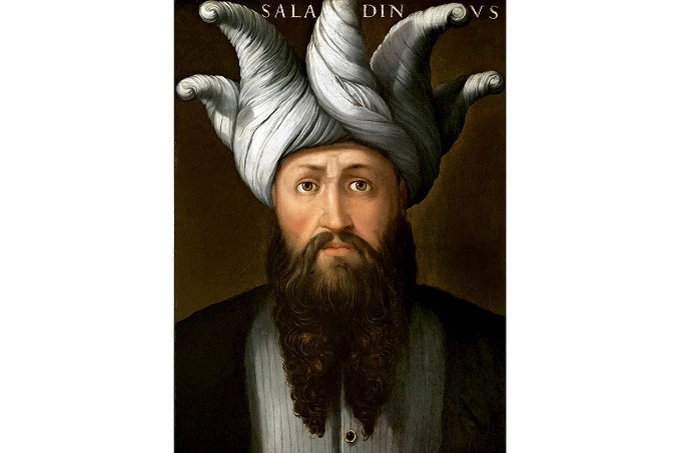

Who was Saladin

Sultan Saladin’s name began to fade after the last representative of the Ayyubid dynasty died in the fourteenth century. Modern Eastern politicians who wanted to follow in the footsteps of the great commander remembered him. What has Saladin’s story been preserved?

Once upon a time, seven Greek cities competed for the title of Homer’s birthplace. Similarly, all Middle Eastern peoples regard Sultan Saladin as a member of their tribe. He protected Islamic civilization from the Crusader Knights more than 800 years ago and returned to it the sacred city of al-Quds, which we now name Jerusalem. Even his opponents could not accuse him of any dishonourable behaviour because he performed it with such dignity.

Most people are familiar with him because Sir Walter Scott retells chivalric romances. Saladin is the result of this. Salah ad-din, which means ” Righteousness of the Faith,” was his real name. But this is really an honorary nickname for Yusuf, who was born in the family of military chief Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb in 1138.

By birth, he was a Kurd, a member of a wild mountain people who fiercely cherished their independence and the Yezidis’ faith. On the other hand, Saladin was born in Tikrit, Iraq, where his father served the local ruler. His mother was an Arab, and he was raised in a strict Islamic environment.

We know very little about Saladin’s childhood. However, it is known that the future hero’s father traveled to Syria in 1139 to serve the atabeg Imad-al -Din Zengi. After evaluating the commander’s ability, Zengi drew him closer to him and granted him command of Baalbek.

After the master’s death, Ayyub backed his eldest son Nur-ad-Din in the quest for power, and in 1146, the latter appointed him king of Damascus. Saladin grew up and acquired an education in this wonderful metropolis, which for an aristocratic eastern child at the time was limited to the foundations of the faith, horseback riding, and saber wielding. Saladin may have been taught to read and write, as well as the fundamentals of versification. Unlike many European kings, he could read and write after becoming Sultan.

The Zengi dynasty’s lands bordered the Crusader nations that arose in Palestine after the First Crusade in 1099. Knights in the East lived the same way as they did in the West. After erecting fortresses in strategic locations, they levied numerous levies on the peasantry, both immigrants from Europe and native Arabs, Greeks, and Syrians.

Their lands were nominally subordinate to the king of Jerusalem, but they were truly independent. Their rulers imposed punishment and retaliation, enacted laws, declared war on each other, and made peace. Many of them had no qualms about robbing trade caravans and merchant ships.

Crusaders benefited much from trade. According to French historian Fernand Braudel, trade turnover between the West and the East surged 30-40 times. Military knightly orders such as the Templars and the Johnites played an essential part in the crusader governments (Hospitallers). Their members accepted monastic vows of poverty, celibacy, and submission to superiors. They also vowed to fight against the Gentiles and defend Christians. A Grand Master presided over each order, to whom several hundred knights were subservient.

The crusaders gradually assimilated into the Middle Eastern political system. They formed alliances with others and exchanged presents since they were at odds with some local authorities. The supporters of the Baghdad caliph were at odds with Egypt’s Fatimid Shiite dynasty, and the Seljuk Turkic empire split into pieces, with control passing to the Sultan’s instructors, the atabegs.

The Zengids were among them, with the purpose of expelling the “Franks” from Palestine, particularly Jerusalem. There were Islamic shrines in addition to Christian and Jewish ones, such as the Qubbat as-Sakhra (Dome of the Rock) mosque, from where the prophet Muhammad, according to mythology, ascended to heaven on the winged horse Borak. After the crusaders captured the city, they were all changed into Christian churches, and Nur-ad-Din Zengi pledged to reclaim them. Saladin helped him in this endeavour.

The road to empire

But first, the young man had to fight fellow Christians on the banks of the Nile, not “infidels” but with fellow believers on the walls of Jerusalem. Nur-ad-Din wanted to conquer Egypt, where the vizier Shewar ibn Mujir rebelled against the local caliph Al-Adid to encircle the crusaders’ possessions. Zengi dispatched an army led by Shirku, Ayub’s brother, to assist the last in 1164.

Saladin, a 25-year-old leader of a hundred horsemen, accompanied him. The campaign failed because the straightforward Kurds were against the Egyptians’ subtlety. Shewar not only sided with his foe, the caliph, at the crucial moment, but he also sought the assistance of Jerusalem’s monarch, Amaury I. In April 1167, the knights assisted in the defeat of Shirka near Cairo and then dug in themselves in the Egyptian city.

Saladin made his first appearance at this point; when his dejected comrades-in-arms were about to flee the kingdom, he and his detachment grabbed Alexandria’s most significant port and prevented the crusaders from getting reinforcements. After lengthy discussions, both parties decided to depart from Egypt, but Shirkuh stayed and became the caliph’s vizier.

In March 1169, Shirkuh died, most likely from poison, and his nephew Saladin succeeded to the position. To the surprise of many, he showed himself not to be a simple-minded slasher but a skilled politician who attracted the courtiers and the people to his side. When al-Adid died in 1171, Saladin took his place without any opposition. His former master, Nur ad-Din, expected obedience from him, but Saladin, having become the Sultan of Egypt, made it clear that he did not need leadership.

Moreover, after the death of Nur ad-Din in 1174, he intervened in his heirs’ dispute. He secretly took away Syria’s property, including Damascus (his father had already died by that time). Saladin beat their kinsman, the powerful atabeg of Mosul, who stood up for the Zengid and forced him to acknowledge his superiority. Enemies attempted to recruit the Sultan’s Assassins, fearsome killers who feared the entire East. But he established a secret service that eventually caught all of Damascus’ assassins. When the killers learned of their execution, the famed “Mountain Elder” preferred to make peace with the resolute Sultan.

Everything was now in place for the attack on Jerusalem. The plan worked: the city was ruled by young king Baudouin IV, who was suffering from leprosy. His potential heirs openly contended for power, thus weakening the Christians. Meanwhile, Saladin gathered and trained a force of former slaves known as the Mamluks. Detachments of horse spearmen and archers were recruited among these skilled soldiers who were selflessly committed to their masters. They advanced and retreated rapidly, leaving behind the ungainly knights in their armor. The other half of the army was made up of forcibly conscripted fellahs who fought poorly and reluctantly yet were able to crush the enemy in large numbers.

After Baudouin’s death, power moved from hand to hand until it reached his sister Sibylla and her husband Guy of Lusignan, who lacked authority and were powerless to stop the feudal lords’ arbitrariness. Baron Renaud de Châtillon, the most brutal of them all, plundered a caravan conveying Saladin’s own sister to her fiancé. She was unharmed and released, but the baron had already seized all of her valuables. He touched the girl at the same time, which was an unheard-of offence. Saladin vowed vengeance, and his 50,000-strong army started a campaign in June 1187.

Lion fight

The Sultan began by besieging Tiberias’ castle. Despite King Guy’s opposition, Saladin led his army into a dry desert, where many knights died from enemy arrows and the hot sun. The fortress was forced to surrender while they were trying to get out.

Saladin met the crusader army between the Horns of Hattin, which contained 1,200 knights, 4,000 cavalry, and 18,000 soldiers, on their way to Tiberias. The decisive battle began on July 4. Fortified on the hills, the Muslims opened fire from above on their opponents, who were suffering from dehydration and the smoke of dry branches set on fire by the Sultan. The knights succeeded in taking the Horns despite losing nearly all of their horses and being besieged by opposing cavalry.

With the help of a small troop, Count Raymond of Tripoli was able to break through the encirclement and flee. By the evening, the rest had to give up. They were captured: King Guy, his brother Geoffroy, the Templar and Johnite masters – nearly the entire crusading aristocracy, except for Count Raymond, who died of wounds after arriving in Tripoli.

Sultan Renaud de Chatillon’s offender was also apprehended. Saladin hacked off his head with his own hand when he compounded his guilt through bold actions. Then, as is Kurdish custom, he soaked his finger with the enemy’s blood and ran it over his face as a sign that vengeance had been exacted. The fates of the other hostages were decided in Damascus.

Saladin ordered the execution of all Templars and Johnites (a total of 230 persons) since they were sworn enemies of Islam. As accomplices of the enemy, Muslim crusader supporters were also executed. Including King Guy, the remaining knights were released after swearing never to battle with the Sultan. Ordinary soldiers were sold into slavery.

Saladin then marched triumphantly across Palestine with no one to defend. Acre and Ascalon fell to him, and only the coming from Europe of the Margrave Conrad of Montferrat with a large detachment rescued Tyre, the last Christian harbor.

The Sultan besieged Jerusalem on September 20, 1187. Because there were insufficient defenders and supplies and crumbling defenses, the city succumbed on October 2. Saladin did not repeat the crusaders’ atrocities: he permitted all of the city’s inhabitants to depart for a nominal payment and even take some of their belongings with him. On the other hand, many poor people lacked money and thus became slaves. There were over 15,000 of them. The winner received immense money and all of the city’s shrines, which were converted back into mosques.

The news of Jerusalem’s fall infuriated and angered Europe. In a new crusade, the rulers of the three largest kingdoms – England, France, and Germany – gathered. The troops marched towards the goal because they couldn’t agree on anything.

The German monarch Frederick Barbarossa was the first to set sail in May 1189. He pursued them on land, taking Konya (Iconium), the Seljuk capital. However, the emperor drowned while crossing the mountain river in June 1190. Part of his army returned home, but the rest made it to Palestine, where a plague epidemic nearly wiped it out.

Meanwhile, Richard I’s English and Philip II’s French were still making their way to the Holy Land by water. They had to fight a lot along the way. King Richard gained the nickname Lionheart by battling against the natives of Sicily who rebelled against him rather than the Muslims.

During another military campaign, he captured Cyprus from the Byzantines and gave it to Guy Lusignan, the exiled king of Jerusalem. The two kings did not arrive in Palestine until June 1191. Saladin made the fatal mistake of leaving Tyre to the crusaders. They were able to recruit help from Europe and lay siege to the formidable bastion of Acre after fortifying there. When King Richard appeared at its gates, a battle ensued between two equal power and brave opponents.

His courage sparked Saladin’s adoration for the English king. The Sultan is supposed to have sent his opponent a basket of snow from the high peaks after learning that he was suffering from a heat headache. Ordinary Muslims were much harsher with Richard, even scaring their children. There were reasons for this: the chivalrous monarch had already demonstrated his harshness. On July 12, Acre fell to him, and he massacred roughly 2,000 Muslim prisoners who couldn’t pay the ransom.

After that, the crusaders moved south, defeating enemy troops one by one. It was then that the shortcomings of Saladin’s army, which consisted of forced people, showed up. The Sultan said in his heart: “My army is not capable of anything if I do not lead it along and look after it every moment.” Needless to say, behind the backs of the fighting Egyptians, the Mamluks were on duty with sabers drawn. The knights did not have this: each of them knew what he was fighting for.

The death rate is increasing

Richard threatened to return the entire coast to Christian dominion as he moved from Acre to Ascalon. With a 20,000-strong army, Saladin barred the king’s path at the castle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191. The superiority of European tactics was once again demonstrated here: the knights were able to quickly construct a defence against which the Muslim cavalry was helpless.

After losing 7,000 men killed, Saladin’s soldiers retreated in panic. After that, the Sultan never again dared to enter into a major battle with Richard. The English king captured Jaffa and Ascalon and began to accumulate strength to attack Jerusalem. However, luck soon turned away from the Christians again: Richard and Philip entered into a fierce dispute for the crown of the already defunct Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The first supported his protege Guy Lusignan, while the second supported Margrave Conrad of Montferrat. After losing the argument, Philip withdrew his army to France in rage. Envy played a part as well: the Frenchman did not perform great feats, and no one referred to him as the Lionheart.

The crusading force had shrunk to less than 10,000 knights, and Richard had to concede that leading them to the Holy City through armies of adversaries was a death sentence. Saladin’s viziers were tasked with equipping and leading all-new armies into Palestine. The villages were disappearing, and the country was on the verge of famine, but the holy war was more important. It was a means of strengthening the Sultan’s kingdom, not an aim in itself.

The Caliph of Baghdad, whose influence had waned but not his authority, sent him his blessing and pledge of complete assistance. Saladin planned a battle against Baghdad in the future to reestablish the great Arab Caliphate. His armies had already conquered Libya and Yemen, and they were prepared to push even further. But first and foremost, the crusaders had to be defeated.

Richard concluded a peace contract with Saladin in September 1192, which was a significant triumph for Saladin. For the knights, just the seacoast remained, and Ascalon was razed under the terms of the treaty. Christian visitors were permitted to travel to Jerusalem and worship at its shrines. The Sultan made one concession: the most important thing is that the dreadful Englishman with a lion’s heart returns home.

Richard fully realized the repercussions of his less-than-chivalrous deed on the way home. He threw down the Austrian Duke Leopold’s flag, which he had hoisted first, from the wall when he took Acre. The duke had a vengeance against Richard and imprisoned him in the castle while he was in his domains. Only two years later, the monarch was released for a large payment. This did not teach the eccentric monarch anything: he promptly got entangled in another conflict at home, and he perished in 1199 from an accidental arrow while sieging a French castle.

With these words, the chronicler summed up the Lionheart’s fate: “Everything that his courage earned, his indiscretion forfeited.” Saladin, his adversary, was no longer alive. He had a fever during his final campaign and died on March 4, 1193, in Damascus. As a protector of the faith, he was mourned throughout the East.

The Sultan’s realm was divided among his heirs after his death. Egypt was given to al-Aziz, Damascus to al-Afdal, and Aleppo to al-Zahir. Unfortunately, none of the Ayyubids possessed the virtues of the dynasty’s founder. They indulged in drinking and entertainment with concubines while entrusting the security of their wealth to ministers and commanders.

Soon after, the Mamluks chose to run the kingdom themselves, and in 1252, they drowned the last Ayyubid, Musa, in the Nile. The Kipchak Baybars came to power after a brutal battle, and they not only drove the crusaders out of the Holy Land and conquered the terrifying Mongols who had seized half of the world. He drove the Ayyubids out of Damascus in 1260, and the dynasty’s final representative died in 1342.

Saladin and his cause looked to have gone down in history. However, the fighter was recalled in the twentieth century, when Arabs rose up against European colonialists once more. The Sultan became a role model for Egyptian President Nasser, Syrian President Assad, and Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, who was proud to be an Iraqi – he was born in Tikrit as well.