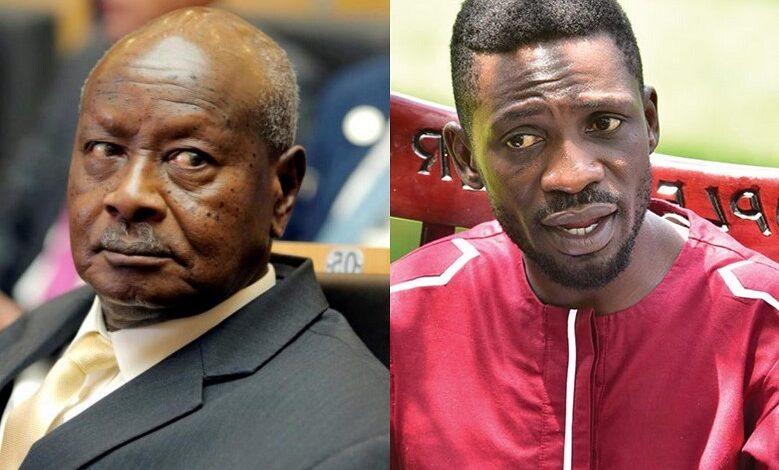

Bobi Wine moves the lines but Museveni is an ally of all time

Under house arrest since the disputed election on January 14, Bobi Wine continues to mobilize Uganda’s streets, not leaving Uganda’s traditional partners indifferent. Slowly but surely, the opponent is getting an international response.

In Uganda, it is no surprise that opposition leader Bobi Wine has rejected the presidential election results in which President Yoweri Museveni won. Under house arrest since the election, he continues to mobilize the streets in defiance of the regime:

“The revolution continues, and nothing will stop the revolution of the people. The regime is desperately trying to close this chapter and pretend that everyone has moved on. But I tell them today: this is only the beginning. We are removing a dictator from power,” he said on social networks a week after the presidential election.

According to Bobi Wine – whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi – the first round of the January 14 presidential election was characterized by numerous irregularities: ballot box stuffing, intimidation, and observers’ arrests National Unity Platform (NUP), his party.

According to the Electoral Commission’s official results on January 16, Robert Kyagulanyi came second with 34.83% of the vote, behind President Yoweri Museveni, who was declared the winner with 58% the vote.

The young opponent maintained that he had won the election and would continue to contest the results. The deadline for any appeal being January 29, the NUP promises to file a lawsuit in the coming days.

In the meantime, some of Uganda’s traditional partners, including the European Union and the United States, who are accustomed to a deafening silence so as not to offend President Museveni, are beginning to react. A sign that the lines are really starting to move…

But Museveni is an ally of all times

Between Yoweri Museveni and Westerners, especially Anglo-Saxons, it is a love of interest that goes back to the late 1980s. Freshly arrived in power in 1986, following a civil war that devastated Uganda, Marxist Museveni discovered capitalist leanings and moved closer to the United States and Great Britain, becoming at the same time the pillar of the Anglo-American strategy in Central and East Africa.

When, in the aftermath of the Cold War, the US decided to reshape the geopolitical map of Central Africa by neutralizing France and its French-speaking supporters in the Great Lakes region, they appealed to him.

Following the example of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, the Ugandan President is an essential ally of Great Britain and the United States in their desire to overthrow the Islamist regime in Sudan, supported by Washington’s great displeasure with Paris.

A symbol of the “new generation of African leaders” (an expression used by Bill Clinton and Madeleine Albrights) US version, he will enable Washington to create the conditions for an American meadow in Central and East Africa, encompassing Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Supported and armed by the Americans, the British, and the Israelis, Museveni is blowing hot air into the crisis that is tearing Sudan apart.

He supports the guerrilla warfare led in the south of the country by John Garang – the leader of the Christian rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), who is fighting the Khartoum regime and whose eminence grise is Hassan al-Tourabi, Islamist leader and protector of Osama Bin Laden at the time when the latter was resident in Sudan.

At the same time, he supports Paul Kagame and the Tutsi exiles trying to overthrow President Habyarimana’s government in Rwanda while having in their sights Mobutu’s Zaire, which has fallen into disgrace in the eyes of Washington since the end of the Cold War. Some observers did not hesitate to call him “Bismarck of the Great Lakes”, in reference to German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, known for his brutality and his propensity to put force above the law.

Since then, Yoweri Museveni has remained one of the most important allies of the United States and the European Union in Africa.

Like Niger, Uganda has become one of the US-led war pillars on terror on the African continent. Ugandan defense forces are involved in operations against Al-Shabaab in Somalia. The Pentagon has also provided Uganda with significant logistical support for missions to clean up the remnants of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in neighboring countries.

Washington provides hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to Uganda, but together with Brussels, they also support Ugandan soldiers’ training involved in peacekeeping operations. And from time to time, the Ugandan number one may play the role of “peacemaker” in the Great Lakes region and Southern Sudan.

Impunity guaranteed

For all the above reasons, the Western powers prefer to turn a blind eye to President Museveni’s dictatorial excesses. Aware of the place he occupies in the Western system, the latter knows that he can afford certain deviations without fear of being bothered by his powerful allies.

Professor Ken Opalo of Georgetown University noted in this respect: “Museveni is an intelligent actor. He has realized that he can be a useful ally to the US in the war on terror, but also in stabilizing the Great Lakes region and East Africa”.

In the name of realpolitik, both the United States and the European Union are constantly forced to strike a delicate balance when addressing issues related to human rights violations and the elections in Uganda. When President Museveni initiated a constitutional reform in 2018 to lift the age limit for presidential candidacy, the western arm of the international community turned a blind eye.

In addition, Westerners find him excuses for acts and gestures that they repress elsewhere. The Ugandan head of state enjoys almost total impunity inside and outside the country, experts, human rights activists, and Ugandan opponents point out.

One of the few times the West has raised its voice against Uganda was when the regime sought to pass a law strengthening the criminalization of homosexuality in 2014, known in the media as the “Kill gay act”. The United States and other Western donors briefly cut aid to the Ugandan government before the situation returned to normal.

A paradigm shift

But with the advent of Bobi Wine on the Ugandan political scene, things seem to be changing. The young opponent has adopted a tactic of harassment and pressure that has put President Museveni’s power to the test. From the beginning of the election campaign to the January 14 polls, the regime was so nervous that it was difficult to recognize the calm and calculating Yoweri Museveni, who is used to containing his emotions in difficult times. Dozens of people were killed during the election campaign, and Bobi Wine was placed under house arrest the day after the poll.

Significantly, Uganda’s traditional partners, including the United States and the European Union, came out of their reservations and condemned the repression of demonstrators and violations of Bobi Wine’s rights.

The European Union even demanded an independent investigation into the violence that followed the opposition leader’s arrest, which left around 50 people dead. More significantly, the US ambassador to Kampala, Natalie E. Brown, wanted to visit Bobi Wine at her residence in the northern suburbs of the capital but was stopped by the police. Following the incident, the Ugandan government accused the United States of “attempted subversion”. A first hit!