Ritual masks and Harlem renaissance: How the First Black Artist succeeded

Lois Mailou Jones has been creating for almost seventy years, not stopping in creative experiments for a second. She opened the world to Harlem – the focus of “black” American culture, shed light on the struggle of African Americans for their rights, never tired of talking about the extraordinary history of immigrants from Africa. Lois Mailou Jones is the first world-famous black artist.

Lois Mailou Jones was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in November 1905. Her father achieved impressive success as one of the first African American lawyers. Parents in every possible way encouraged Lois’ desire to draw – from childhood, and she was unusually talented. They interacted with many famous African American artists and writers, and Lois grew up in an intellectual and creative environment, absorbing her ideas and moods like a sponge.

Lois began her studies at the Boston School of Art, attended evening classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and studied costume design at Grace Ripley’s studio, where she first thought about using African traditions in design. Lois’s first solo exhibition took place when she was only seventeen.

In the summer of 1928, Lois attended Harvard, where she decided to concentrate entirely on painting, leaving design.

Lois Mailou Jones believed that learning should be a lifetime – after all, it was the craving for knowledge that allowed her family to take their place in society. She researched African masks at Columbia University and received her BA in Art Education from Howard University, where she subsequently became active in teaching.

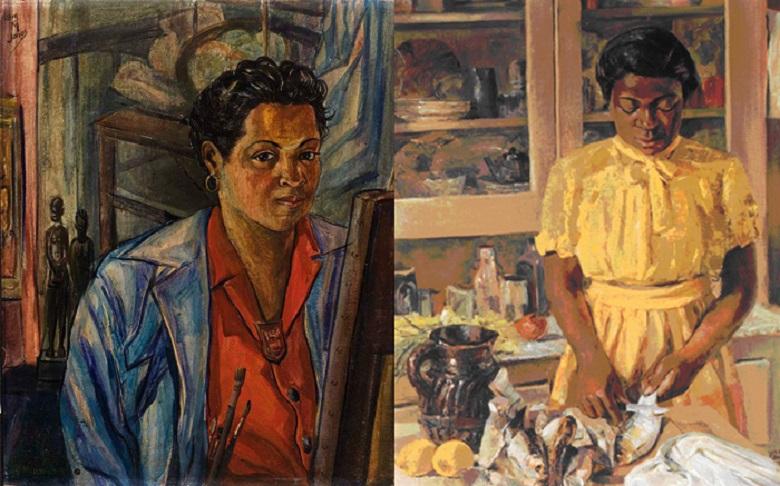

Her creative career started in the 1930s and lasted almost until the end of the 20th century. Jones’s artistic style varied with the experiences she received through learning, socializing and traveling.

Traveling has become the primary source of inspiration for her, which changes her worldview and creativity. Europe, America, Africa – across continents and countries, Lois carried the banner of the identity of black culture, learning new things about her ancestors and expanding knowledge about the world around her. Everywhere her work aroused the deep interest of critics and recognition of colleagues.

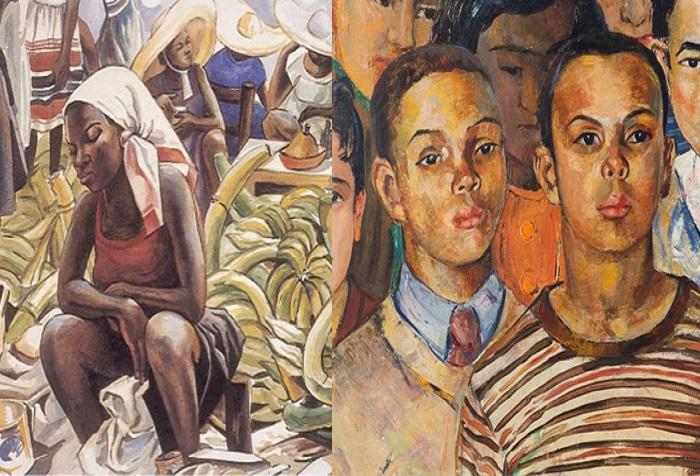

Starting as a realist artist, she went through a passion for post-impressionism and cubism, adopted techniques from traditional African art, remaining recognizable in each of her works.

Lois was also involved in teaching. She was refused a job at the Boston Museum School, which once provided her with an annual scholarship. The director said she should try her luck in the south, where “her people live.”

In North Carolina, Lois Mailou Jones managed to find a job – she taught dance, piano, and physical education, coached a basketball team, and led a church choir. In the 1930s, Howard University invited her to teach painting and design, a work that lasted until 1977.

Mailou Jones strove to ensure that her students find their style, drawing inspiration from their national roots. Lois’s seminars turned the university auditorium into a huge workshop, where everyone was busy with their creative experiments.

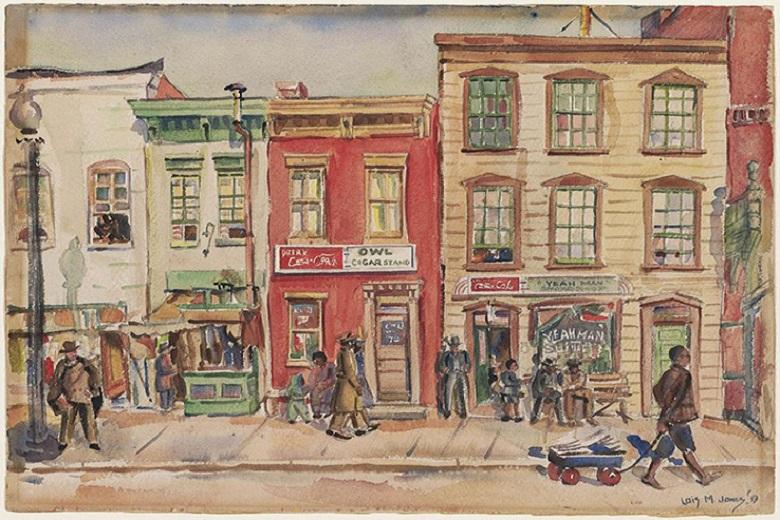

The summer spent in Harlem was a turning point in her work. The “Harlem Renaissance”, the rise of cultural awareness of the inhabitants of Harlem, and the development of Harlem music and poetry inspired the artist so much that she decided to take a direct part in this movement, most important for African American culture.

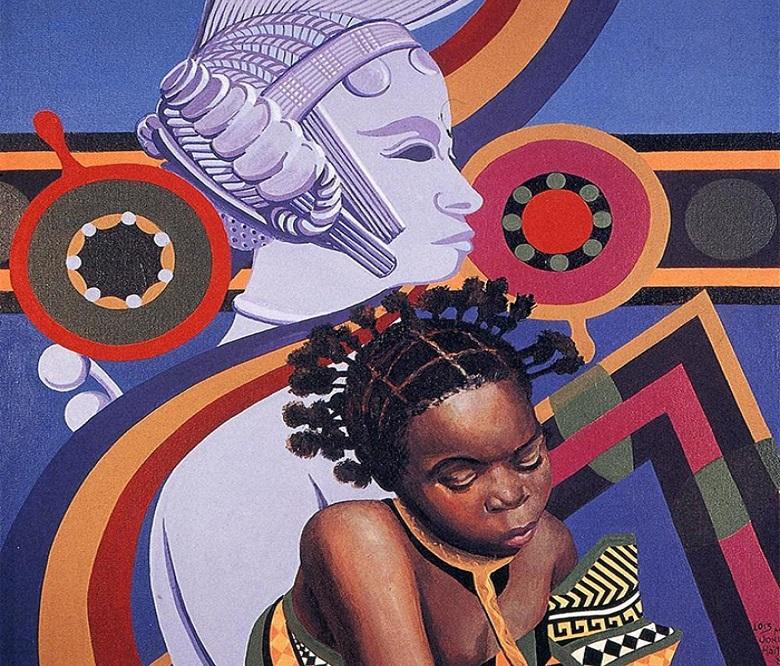

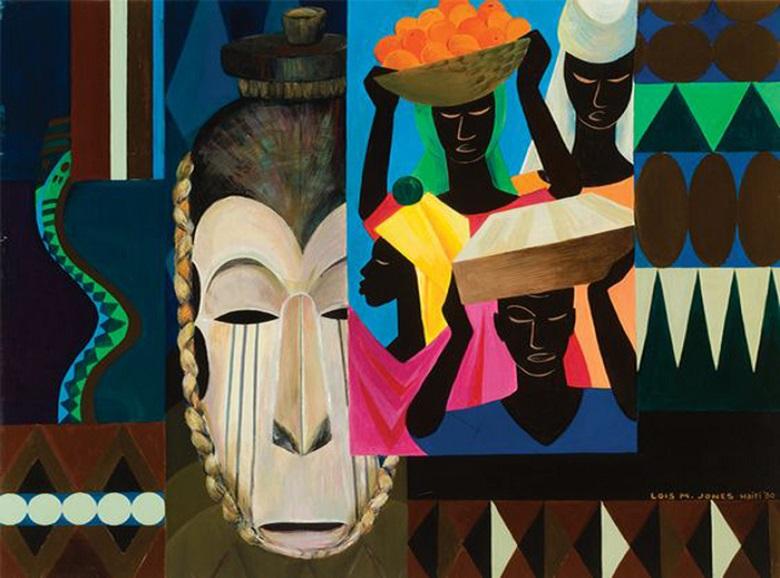

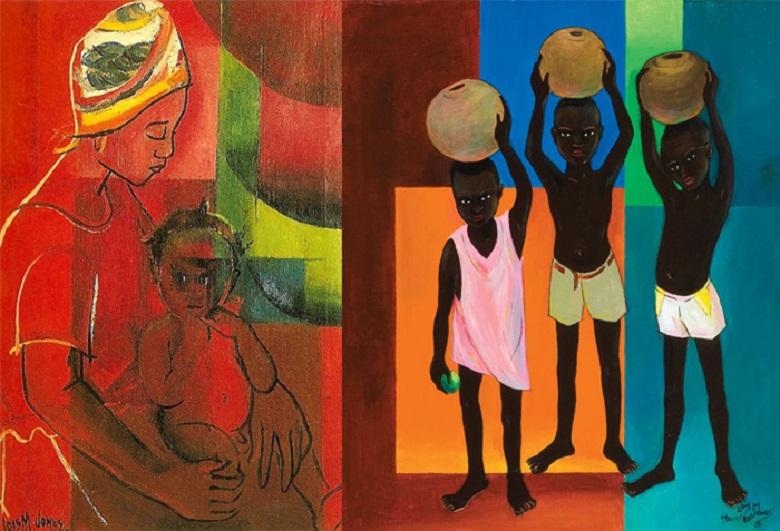

Lois painted portraits of the stars of Harlem and its common people and used African painting to create decorative panels. African masks have become a recurring motif in her canvases.

In 1937, Lois received a scholarship to study in Paris, where she created many watercolours. Paris applauded Lois Mailou Jones’s talent and courage. She spoke with love of that time because she did not feel like a second-rate person in France, as often happened in the United States.

In the 40s, art galleries in Massachusetts and other regions of the United States refused to accept works by African American artists, and it turned out that Lois was much more famous and recognized in Europe than in the United States.

Mailou Jones managed to exhibit anonymously in American galleries. Already in the 90s, the Corcoran Gallery made an official apology to Lois Mailou Jones for its discriminatory policies. In response to the oppression of those years, Lois wrote a realistic and terrifying painting, “Mob’s Victim”, where she depicted a man before lynching.

While studying at Columbia University in the 30s, Lois met the famous Haitian artist Louis Pierre-Noel. Their romantic correspondence lasted twenty years, and only in 1953, they got married in the south of France, which they both loved so much.

Louis’s frequent visits to his homeland inspired Lois to create forty-two works dedicated to Haiti. This project was warmly supported (including financially) by the Haitian government. In addition, Lois, who had a deep knowledge of the arts, was involved in the research, preservation, and promotion of the work of contemporary Haitian artists.

Lois’ scientific research includes a project to study the creativity of African American and Caribbean artists. The creativity of black women was completely invisible in a world ruled by white men. Lois was unbearable to see such a stunning layer of modern culture being ignored with her desire for justice.

Lois worked tirelessly until the last day of her long (ninety-two years!) And eventful life. Paintings, masks and costumes, book illustrations, scientific publications, and exhibition projects that glorified the heritage of “black” culture have made her one of the most influential artists in the United States and the world.

Lois’s works are in many museums and private collections. The Clintons own a series of her landscapes. At the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the same one that once refused to hire Lois, the Lois Mailou Jones Foundation has established a scholarship to support outstanding young artists.