The dark history of electric chair, the invention that promised painless execution but was crueler than ax

On August 6, 1890, William Kemmler became the first inmate to be executed with a thousand-volt discharge. The method pitted two giants from the US electrical industry against each other. The times it failed and had to be killed on a second try. The condemned man who survived. And the change for the lethal injection

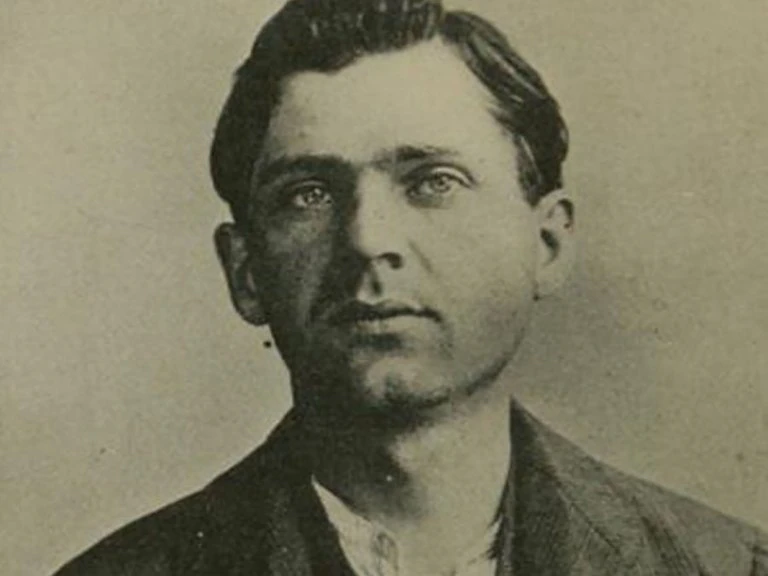

As old Chesterton would say, not even with the best of wills could it be said of him that he was a great man. William Kemmler was a street vegetable vendor in suburban Buffalo, New York. He was also a dangerous and violent alcoholic when he got drunk and during his hangovers.

On March 29, 1888, hungover, he argued very hard with Matilda “Tillie” Ziegler, his girlfriend, his wife. Kemmler accused her of wanting to steal his miseries to flee from that hell with a friend of both. Caught in a sudden calm, Kemmler went to the barn, returned with an ax, and killed Ziegler with twenty-seven blows.

Then he went to the neighbor’s house and confessed to his crime. Forty days later, on May 10, they tried him, found him guilty, and sentenced him to death.

Kemmler became the first human to be executed in a brand new invention designed to kill without pain: the electric chair. Until then, the judicial method of death in the United States was hanging. At the time, this was also a procedure that guaranteed a painless death.

Killing without suffering is impossible; that’s how the most modern state faces it, with the most sophisticated advances and refined techniques. Neither the executioner’s medieval ax, the sharp guillotine, the fearsome vile club, or the most modern lethal injection guarantee a pass to the other pious and painless world.

The executions always depended on the arts of the executioner, and there were pious, crooks, cruel, drunks, fools, and, very few, efficient. The one who executed María Estuardo needed three blows and two axes to separate the head from the body. It is true that no one comes back from the other side to explain what they felt, but witnesses always describe a scene of horror.

When Kemmler calmly went to look for his ax, a more “humane” execution system was being studied in New York, thus, in quotation marks, than the gallows. Hanging someone to kill him requires technical specifications that were not even taken into account at the end of the 19th century: strength of the rope, the weight of the condemned man, exact place on the neck where to place the knot, all destined to kill by breaking the neck and not by suffocation.

On July 20, 1944, the conspirators who wanted to assassinate Adolf Hitler were hung with piano strings, a guarantee of very slow and horrible death by suffocation. In turn, the piano strings hung from butcher hooks for the condemned to “dance” to the delight of their judges and executioners.

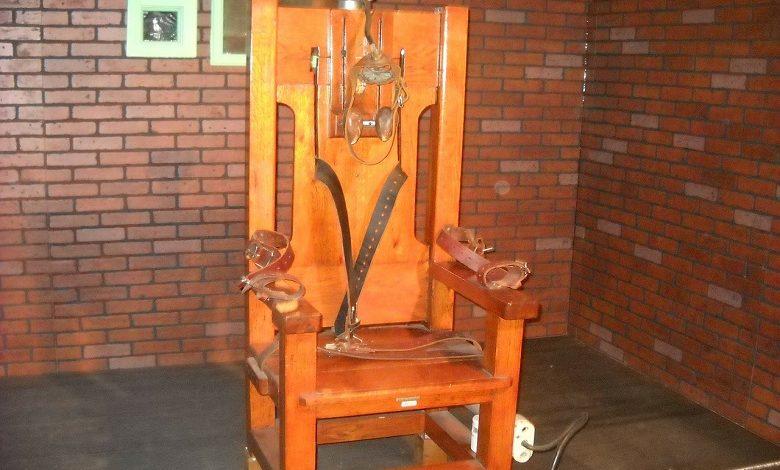

In 1889, with Kemmler already sentenced to death, the Electric Execution Law came into force in New York: the first of its kind in the world. Edwin R. Davis, an electrician at the state capital Auburn prison, was asked to design an electric chair. The guy complied because he was a picky official.

He designed a chair made of insulating material, equipped with two metal electrodes joined with a rubber band and covered by a damp sponge; the humidity favors the circulation of electricity. The electrodes were to be applied, one to the head and the other to the back of the convicted person. Detail more or less, the model was eternalized in almost all of the United States.

So Kemmler, who was going to die, now had two methods to choose from: hanging or electrocution. At a press conference days before his death, he said: “I am a criminal, and I must die. Very good. But not on the gallows: in that chair that they have invented, more modern ”.

On August 6, 1890, one hundred and thirty-one years ago, Kemmler was seated in Davis’s electric chair. They tied him up, attached the electrodes, and applied 700 to 1000 volts for seventeen seconds until something went wrong with the generator.

The witnesses smelled burned meat, but Kemmler was far from dead; he was a little charred, it’s true because that is how the electric chair kills, but he had to wait between groans of pain and an absence of unconsciousness that was not in the manuals: he supposed that the first thing that caused the electric shock was the loss of consciousness of the condemned man. When the infidel generator recharged, Kemmler was given a second electrical shock of between 1030 and 2000 volts for two minutes. That did end his life. Smoke was rising from the dead man’s head when the ropes were removed.

The autopsy revealed that the electrode on his back had burned the spine of this man who thought that modernity was synonymous with piety.

A renowned witness summed up everything with an ironic phrase: “It would have been better if they had used an ax.” The one who spoke like that was George Westinghouse, embroiled in an electrical dispute that, in a way, was the one that sponsored the chair. Westinghouse was at odds with or competing with Thomas Alva Edison for implementing a domestic electrical supply system.

There was more than the search for a more merciful execution system: a fierce commercial battle was raging in which millions of dollars and the prestige of these two electricity giants were at stake.

Edison advocated a direct current electrical system, while. Westinghouse, who followed in the footsteps of Nikola Tesla, advocated the use of alternating current of higher voltage and conducted by overhead cables. Edison was driving lower voltage and underground cables.

In the Menlo Park laboratory, Edison asked one of his engineers, Harold Brown, to create an electric chair that runs on alternating current, that of his competitor Westinghouse, to discredit perhaps not his rival, but his opponent’s aspirations.

Brown put to work hard, put together a prototype, and took it for a walk through several American cities to demonstrate the benefits of his creation. Before hundreds of spectators, he ended the lives of dogs, cows, horses, hares, and even that of an orangutan.

In 1903, when the electric chair was accepted, the rivalry between Edison and Westinghouse led to the death of an elephant from the Coney Island circus. His name was Topsy, and he had killed his coach, a son of a thousand frustrations who fed him lit cigarettes.

They wanted to hang her, but the animal defense societies protested. Ed ison, who wanted to demonstrate the dangers of alternating current, prompted his electrocution. It is all filmed. It is not pleasant to see.

Still, Edison and Westinghouse were against the electric chair. Nor was it a question of piety, but of economic interests: both feared that American consumers would reject the current that burned those condemned to death circulated in their homes. Edison allegedly kept himself apart from Brown’s investigations and always denied any connection with the electric chair.

But denying Edison’s influence on Brown’s work is like giving the doll what the ventriloquist says. Brown did not change much the mechanism of Davis, his colleague from Auburn prison, but he refined it, always with the idea of painless death.

How does the electric chair kill? The elemental principle remains unchanged: electricity is circulated through the body of the condemned person, with an electrode on the head and another on one leg, both shaved to facilitate driving, all moistened for the same.

Two electric shocks are applied for several minutes: voltage and time depend, like the rope of the hanged man, on the structure, weight, and condition of the executed.

The initial voltage is 2000 volts, and, in theory, it serves to break the skin’s resistance and cause unconsciousness. It doesn’t happen often. The voltage is then lowered to prevent the prisoner from burning, literally.

A current flow of about eight amps brings the interior temperature to about 60 degrees Celsius. The damage that this current flow and temperature produces in the internal organs causes death if cardiac arrest or respiratory paralysis has not arrived before.

The practice, according to witnesses, suggests another coven scenario: hair and skin burning with the prisoner still conscious. The high temperature of the internal organs causes uncontrolled jumps, despite the lashings, and the condemned defecates, urinates, vomits blood amid an intense smell of burned meat.

The intensity of the execution caused, on more than one occasion, the moorings that keep the prisoner immobile, which had to interrupt the execution and restart it once the dying man was restrained to the chair. Experts have proposed certain changes to the saddle, all refined, to avoid or hide those sad drifts.

The American State of Nebraska, always with that spirit that says that efficiency should not be sprinkled by chance, drew up an execution protocol that ordered the condemned to be subjected to a discharge of 2,450 volts for 15 seconds. After a wait of fifteen minutes, a doctor checked if there were still signs of life in the condemned man, which seemed unlikely.

But in February 2008, after one hundred and twenty-eight years of use, the Nebraska Court, by six votes to one, decided that electrocuting those sentenced to death “inflicted immense pain and agonizing suffering and cruel and unusual punishment.” What was prohibited by the Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution?

After Kemmler and nine years after his execution, Martha Place became the first of twenty-six women to be executed by electric chair in America. She was found guilty of murdering her stepdaughter, Ida Place.

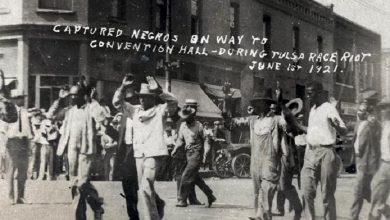

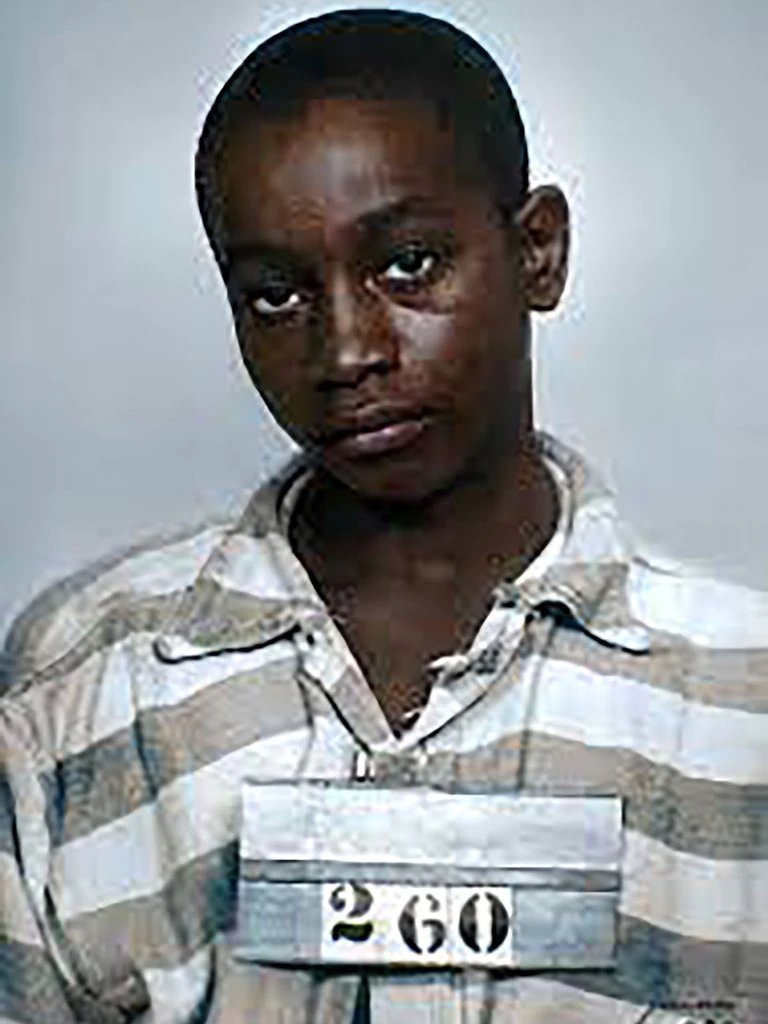

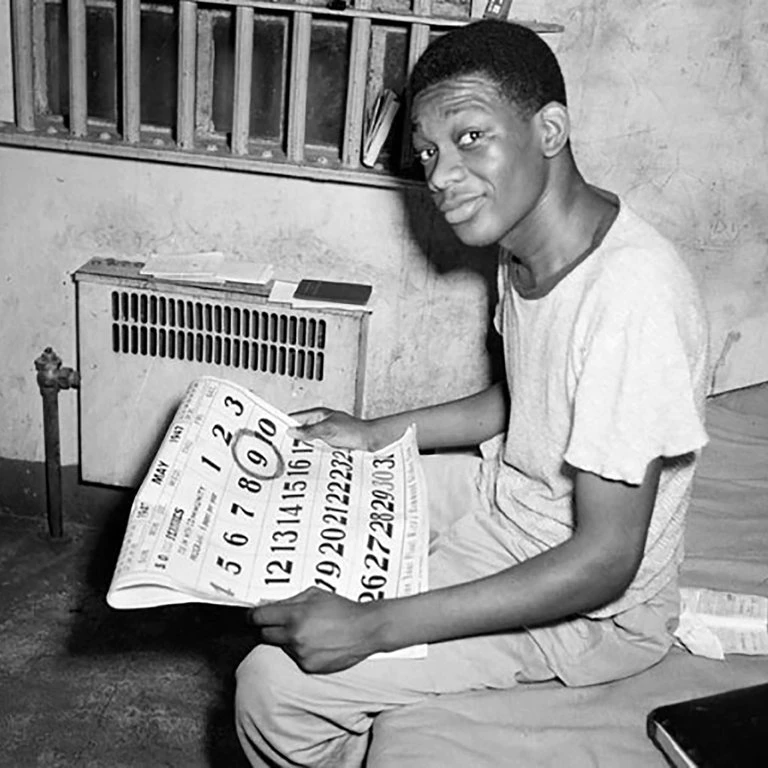

On June 16, 1944, George Junius Stinney Jr., a 14-year-old African-American boy, died in the electric chair of the South Carolina State Penitentiary, accused of murdering two white girls: he was the youngest human being to be executed in the United States. In 2014, seventy years after his death, Stinney Jr. was acquitted of his charges, and his conviction was declared void by the South Carolina circuit court.

The case of Willie Francis is famous, a 17-year-old black teenager sentenced in 1946 to die in the electric chair of Louisiana for the murder of Andrew Thomas, owner of a pharmacy where Francis worked.

The boy survived the first electric shock and then successive shocks while shouting: “Stop! Stop! Let me breathe! “. A drunken official had improperly installed the chair.

His lawyers then demanded the release of Francis because he had been “executed,” as ordered by the sentence. Only he hadn’t died. A new execution, lawyers argued, would violate the United States Constitution. The case went to the Supreme Court (Francis vs. Resweber – 329 US 459 (1947), which rejected the defense arguments. Francis was executed on May 9, 1947. His case is the first of a serious failure in the electric chair and a death sentence that was carried out twice.

Leon Frank Czolgosz, the anarchist who assassinated the president of the United States, William McKinley, in 1901, was executed in the electric chair in the same Auburn prison where Kemmler died.

In 1927, in Boston, the Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair for a crime they had not committed.

In 1953, the marriage of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg died in the electric chair in Ossining, New York, accused of revealing American atomic secrets to the Soviet Union.

In January 1989, in Florida, Ted Bundy was also executed in the electric chair, the serial killer who confessed to murdering thirty women. However, he is suspected of committing many more crimes.

The paradox of the death penalty, the electric chair fell out of favor, if possible, because the United States suspended executions in 1966 and resumed them ten years later, but by lethal injection which, now, sounded like a painless procedure, neat and unforgiving. It was not so.

The various combinations of hypnotic, sedative, and analgesic drugs, plus the use of neuromuscular blockers and the prohibition of using certain drugs to cause death, added to some unsuccessful executions in terms of the rugged, caused the American legislation to release the convicted prisoner.

It’s Kemmler’s theorem backward: he wanted the modern chair before the old gallows; today, many condemned to death want the old chair to the modern lethal injection. Given the possibility of freely choosing how to move to the other world, if that choice can be called freedom, the chair continued in use in the United States until February 2020.

Killing your neighbor, even under the umbrella of legality, is not comfortable, nor is it painless, nor is it insensitive, nor is it easy, nor is it progress; it is a cultural trait, but it is not culture; He is not indifferent and cannot be dressed in silk.