Three professions that have disappeared these days: that’s great!

Those who now sigh for the good old days, when “women were chaste, honor was still in use, and all food was organic,” are simply unaware of the past. Just three centuries ago, a child in early childhood could be bought and mutilated to be resold at a profit. A harmless removal of a blister could end in fatal blood poisoning. After death, a person was often not allowed to lie down adequately in his own grave.

In those very days, in addition to the generally accepted and even relatively honest ways of making money, there were many professions whose ethics would seem repugnant to us today. Three are in this review.

The Body Snatchers

For a long time in England, postmortem life was in full order, as it was throughout the rest of Europe. It was forbidden to dissect corpses – a vessel of God, after all – and violators were dealt with harshly and unhygienically. Surgeons had to rely on the teachings of Gallen, the Roman doctor who autopsied mostly animals and drew conclusions about the human body by analogy.

But in the very early 16th century, King James IV of Scotland, by his edict, authorized a corporation of barbers and surgeons to dissect four bodies of executed criminals in one year. And immediately, two problems arose. Firstly, only four corpses for all, including students – it is negligible, and secondly, at the beginning of 16 centuries, hanging was in England and Scotland not the only variant of execution. And after some of its ways, the bodies ended up on the table, let’s say delicately, not quite in a marketable form.

Besides in many sentences, in addition to the actual method of death, there were also various interesting variants of posthumous punishment like “and expose his body in chains for intimidation for a week”. It is clear that after the corpse had been hung for a week in an iron cage – and the birds had worked on it extensively – there was almost nothing left for the medics.

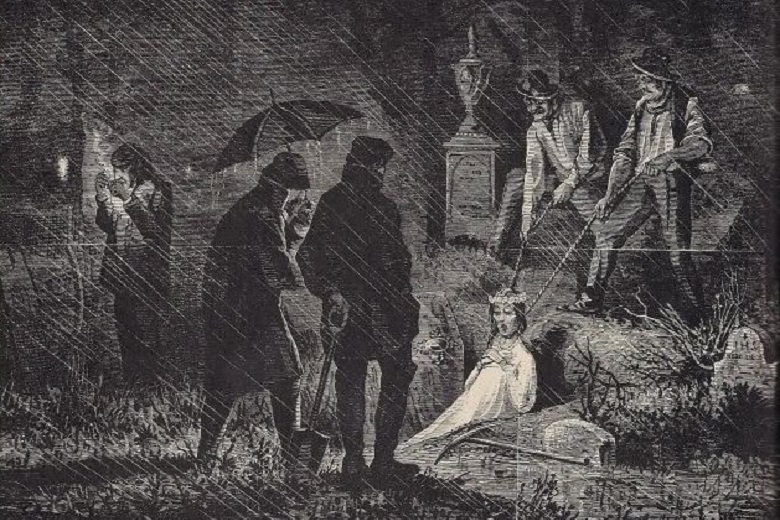

In 1540, the same law was passed in England. The quota increased little by little from century to century, but still, the few thousand doctors, barbers, and painters who joined them, who just wanted to portray a human being rather than a shadow on the wall, desperately lacked corpses. In such a situation, a black market could not help but emerge – and it did, along with people who made stealing corpses from cemeteries their profession. They were ironically nicknamed “resurrectors” in England.

The scale and turnover of the underground corpse market are amazing. The average rate of a fresh dead man ranged from 2.5 to 15 pounds, from 3 to 23 average monthly wages of a male worker (and then they worked 14 hours a day, 6 days a week). But these are prices, so to speak, for “basic equipment”, and the corpses of those who died from some unusual disease or were distinguished by curious congenital deformities were much more expensive – up to several hundred pounds.

No matter how hard the poor English commoners tried to protect their posthumous rest from the “resurrectors,” nothing worked. The richer ones ordered steel coffins that were as strong as a bank safe, the relatives of the poorer ones tried to delay the funeral until the body was clearly decomposing, watchtowers were erected in cemeteries, and still, the bodies were stolen by the thousands every year. If there is a demand, there will be a supply.

By the way, the scheme by which the body snatchers worked is very interesting. As a rule, cemeteries were “bombed” by a team of six to eight people. Everything was worked out in detail: an inclined manhole was dug to the end part of the coffin, it was broken out, after which the body was pulled to the surface with loops and hooks, undressed, everything taken off was put back, the coffin was pinned, the manhole to it was carefully buried, the “client” was loaded on a cart and driven away. Why all this trouble? Greetings to the English legal system and the ability of the subjects of the crown to manipulate the system.

The fact is that up until the middle of the 19th century, there was no rule in England about the right to own one’s own body. Therefore, a corpse after death was like a “nobody’s” corpse, unlike the underwear, shroud, and other goods put on it, which were already the property of the deceased’s relatives.

In case of capture, the gang of “resurrectors” could expect at best a punishment for some “violation of public peace” with an extremely small term of imprisonment. But they could be tried as thieves for stealing personal belongings from the coffin. They tried to leave the coffin intact for the same reason – to avoid falling under the law on the desecration of graves.

It’s the same way British criminals work – they really know how to honor their country’s laws. For example, in burglaries of houses, apartments, and stores, one group goes in first to break down windows and doors, but does not enter the premises, followed by another group that is already taking things out. That’s because burglary carries up to 14 years in prison, theft carries up to seven, and damage to private property carries only a few months.

The “resurrectors” business flourished and brought in superprofits until 1832, when a law was passed that permitted the autopsy, without any quotas, of bodies found in prisons or state workhouses, bodies found in the street, and unclaimed by relatives, and other “superfluous” people. Even after that, the body snatchers did not abandon the scene, switching to stealing the corpses of celebrities for ransom. So in 1978, they stole Charlie Chaplin’s body from the cemetery in Vevey, Switzerland, and demanded 200,000 francs from his widow.

Comprachicos

To a person who has not read Hugo’s novel “The Man Who Laughs”, this word might sound like some amusing Latin Americanism like “banditos gangsteritos”. In fact, this was the name of the people all over Europe up to the middle of the 18th century who bought up and kidnapped children with congenital deformities. And not only the buyers – when no suitable human material was available, but the comprachicos also made freaks out of ordinary children.

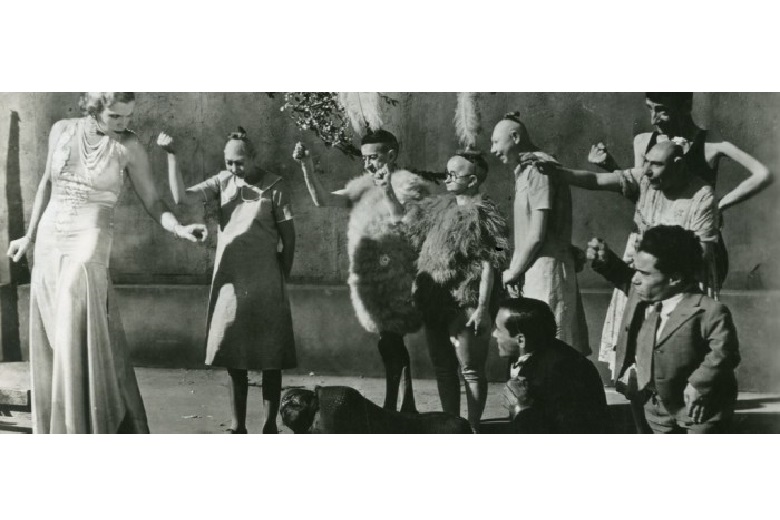

People with obvious external grotesque deviations attracted general interest instead of compassion until quite recently – at the beginning of the 20th century, dwarfs and bearded women still performed in the famous Barnum circus. Unusual-looking representatives of indigenous peoples from different parts of the world at the same time were generally shown in zoos along with elephants and zebras. And in the 18th century and earlier, children with disabilities were also a valuable commodity.

Giants, dwarfs, hydrocephalic, twins, and the like were bought to the court of kings and aristocrats – as jesters, servants, living toys, and witty entertainment for guests. Likewise, they were purchased to entertain crowds in circuses and fairs or in brothels to satisfy the tastes of a, particularly discerning clientele.

Semi-underground human trafficking has always existed in Europe, which formally did not know slavery. Most often, the poor sold their children: a lot was born, and there was nothing to feed the extra mouths. Living goods were in demand, but it was the deviations and deformities that attracted the special attention of buyers. The demand was satisfied by the Comprachicos, who were in a continuous journey from city to city, from village to village, and everywhere buying up children and adolescents.

But if there were no suitable disabled people, then an anesthetic broth, a knife, threads, and ancient techniques were used to turn an ordinary man into a living caricature. The main character of the novel, Hugo, had an eternal smile cut out on his face. Others had their growth slowed down, or the bones were removed from their joints, or the spine was broken in a special way so that a hump would grow on the back.

Hugo argued that at the same time, the Comprachicos helped the royal houses solve problems with “inconvenient” heirs and superfluous figures in the “game of thrones”: why kill and take a sin on your soul, when you can disfigure and sell to street acrobats? Only at the end of the 17th century, William III of Orange, who had just ascended the English throne, banned the activities of the comprachicos and began to systematically persecute them. But trafficking in children with disabilities continued almost as early as the early 19th century.

There are almost no traces and references from this whole story in the sources. And many are even sure that the Comprachicos are nothing more than a creepy invention of Hugo, who was based on obscure rumors of his time. But this profession still existed, and apparently, even today, did not completely die everywhere.

Barbers

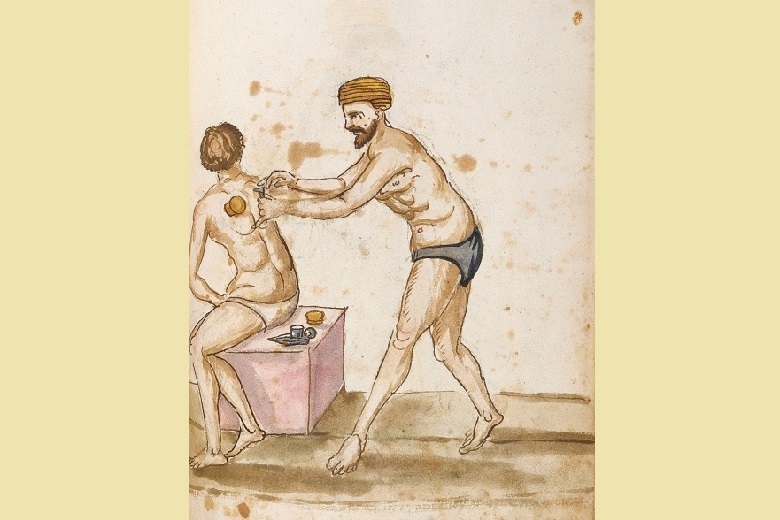

Remember we mentioned them at the very beginning? Yes, in those good old days, a barber was not at all what a hairdresser or a barber today, and there is nothing strange about the fact that they were allowed to open corpses along with doctors. In addition to their main specialty, barbers worked part-time with what we would call today “paramedicine”: they removed calluses, opened up abscesses and boils, tore teeth, cauterized wounds, and opened blood.

That is, in fact, it was such medicine for the poor – the services of a real doctor who graduated from the medical department of the university were fabulously expensive, and only a few could afford it. But everyone knew that bloodletting is the best medicine for almost half of diseases. And they were treated by barbers.

Of course, the barbers had no idea about sterility, the rules of treatment and care, and the pharmacopeia, so that “often” their treatment turned out to be worse than the disease and quickly drove to the grave.

The “surgeon” takes a dirty and rusted contraption, presses it firmly against the dais, cuts through the skin, does the torch manipulation again, places the jar again, and in three to five minutes, it is full of blood. The jar is removed, the blood is right on the floor. Then the bath attendant pours a pail of water over the patient, and he, tattooed, walks out into the dressing room. After that, a consultation on the ‘usefulness’ of the jars usually began.