Why and how ancient people artificially arranged mass extinction of animals

Throughout history, the flora and fauna of the earth several times came close to their complete extinction. Most species that lived on the planet at one time or another have now become entirely extinct. Giant volcanic eruptions, meteorite falls, and global climate change are not the only reasons for the extinction of some animals. Homo sapiens have been responsible for the disappearance of certain species of large (and not so large) predators.

The growing brain of homo sapiens

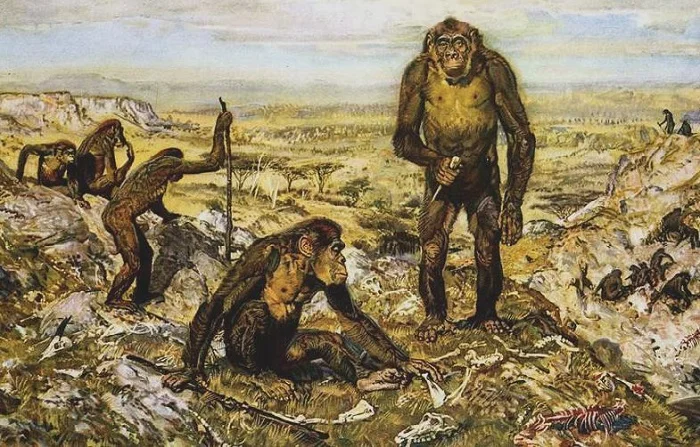

In the course of evolution, the brain of the ancestors of modern humans, homo sapiens, increased in size very rapidly. This meant only one thing – the ancient man became smarter and more resourceful with each new generation.

The growing instincts, skills, and abilities allowed prehistoric humans to climb to the top of the food chain gradually.

It is now almost certainly proven that behind the disappearance of such large animals relatively recent past, such as mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, or giant sloth, is the primitive man. Naturally, along with such large prey, the predators that hunted them – sabre-toothed tigers, cave lions and bears – also became extinct.

Involuntary extermination

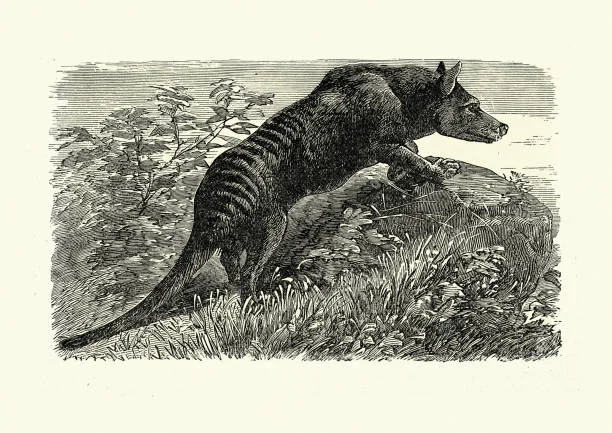

In the first half of the 20th century, one predator that went extinct was the Tasmanian marsupial wolf, the thylacine. These animals were mass exterminated by the colonists for nearly two centuries.

However, the epizootic (animal epidemic) of an unknown disease, presumably the canine plague, which Europeans brought to the habitat of Tasmanian wolves together with their “four-legged watchmen”, finished off the marsupial wolves.

When people came to their senses – it was too late. The last marsupial wolf died in the zoo of Hobart, the capital city of Tasmania, in 1936. Its species had fallen victim to artificial extinction. But the earliest human ancestors were the first to learn how to arrange such extinctions of animal species even before homo sapiens appeared on earth.

Not by climate alone

In early 2020, an international team of scientists from Britain, Switzerland, and Sweden published their report after a long work on its excavations in East Africa.

The experts concluded that the sharp decline in predator populations about 4 million years ago is directly related to the growth of the hominid brain and an increase in the diversity of vegetation, not climate change, as previously thought.

One of the study leaders, professor at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) Soren Faurby, emphasized in the report that climate changes in East Africa over the past 4 million years have been very small. And they would hardly have been able to provoke the mass extinction of large mammalian predators.

At the same time, palaeontologists have noted a significant increase in the brain of large hominid species. However, there were still at least 3.7 million years before the appearance of homo sapiens. This indicates that the main suspects in the organization of the extinction of Pliocene predators are the first ancestors of modern humans, australopithecines, who appeared at that time.

Deadly competition

But how could these primates, barely out of the trees, stand on two legs and make a killing spree for the predators? Predators who were bigger and stronger than australopithecines. The answer lies in the organized nature of the higher primates. Hominids grouped, but not to kill their direct competitors for food.

Large brain Australopithecines allowed them to apply a completely new strategy for finding food. Cunning came to the aid of great apes. Hominids learned to steal or take away (by scaring off their numbers) the prey that other predators caught in the hunt.

Kleptoparasitism feeds

In their January 13, 2020 report published in the journal Ecology Letters, archaeological and paleontological scientists confirmed that about 4 million years ago, the population of large predators on the African continent began a catastrophic decline.

It was at that time, they speculate, that human ancestors began to obtain food through kleptoparasitism.

This method of obtaining food is not the invention of the ancestors of homo sapiens. African lions are now successfully hunted by kleptoparasitism, or, simply speaking, by taking food by one animal from the one who got it—taking away from the cheetahs killed by those antelopes.

Similarly, in prehistoric times, Australopithecines were hunted. The hominids stole prey from large predators or took it “by force”, driving away from the hunter who caught it. This survival strategy is quite viable when it comes to saving resources for hunting.

Interestingly, modern humans often become “victims” of other animal kleptoparasites themselves. For example, seagulls on beaches or monkeys in Hindu temples steal or take food from gaping tourists.

Instead of an epilogue

The success of the kleptoparasitism strategy among Australopithecines led to the rapid growth of human ancestors. At a time when other large carnivores were forced to starve. Their numbers began to decline – the first artificial extinction began.

It won’t be long before hominids learn how to hunt pretty well on their own. This will be the “control shot in the head” for many Pliocene and Pleistocene predator species.

The struggle for resources would be triumphantly won by primitive humans. Turning dozens of animal species (both predators and their victims) into fossils.

Further, homo sapiens just continued the primitive strategy of artificial extinction, which continues, by the way, to this day.