Operation Green Sea: Anti-colonial struggles in Guinea-Bissau

On the night of November 22, 1970, a group of soldiers landed stealthily near the city of Conakry, the capital of Guinea, under the leadership of Portuguese colonial officials. The invasion intended to overthrow the government of Ahmed Sékou Touré and kidnap Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral, the revolutionary symbol of the struggle against Portuguese imperialism in Africa.

The “Operação Mar Verde” which means “Operation Green Sea”, this is the name of the military action, took place within a broader conflict: the one fought between the Portuguese regime and its African dominions of Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique to which it had refused to know independence. The secret operation marked a turning point in this long war, but not in a sense hoped for by the invaders.

To understand the events, we must first take a step back and understand why in 1970 the Portuguese military was engaged in Africa, who Sékou Touré and Amilcar Cabral were and why the latter was so important to Lisbon.

Portuguese colonial war

Operation Green Sea took place in a very particular context, given that the so-called “Portuguese Colonial War” was a decidedly atypical conflict. What triggered it was the decision of the fascist regime in Lisbon not to withdraw from its colonial dominions in Africa and recognize their independence at a time when France and the United Kingdom were abandoning the continent.

During the decolonization of the 1950s and 1960s, in fact, the nationalist regime of the Estado Novo (one of the longest-surviving authoritarian regimes in Europe) needed the overseas dominions to fuel its propaganda and their exploitation to sustain its weak economy.

As the other African countries gained their autonomy, independence movements were born in the territories occupied by Portugal, similar to those that were leading the new states, but Lisbon categorically refused their requests.

At that point, the only way left for the independence movements was the armed struggle: thus began a conflict that lasted from 1961 to 1974 with different phases. To lead the independence in Angola and Mozambique were respectively the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) and the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA), while in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde the leadership belonged to the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), all three of Marxist inspiration.

The three former colonies do not border each other, so from Lisbon’s point of view, it was a single conflict fought on three different fronts. Guinea-Bissau had a united anti-colonial front, unlike the other two, which allowed a small group of militants and their charismatic leader to nail the occupiers in what is called “Portugal’s Vietnam War”.

Amilcar Cabral, the PAIGC, and Guinea-Bissau

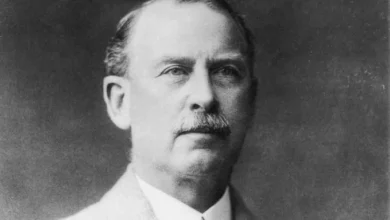

The pre-eminent figure of the PAIGC – and one of the symbols of anti-Portuguese independentism – is undoubtedly Amilcar Cabral, the revolutionary who was the main target of the 1970 Green Sea operation. Intellectual, writer, and political theorist, Amilcar Cabral was one of the most important leaders of the anti-colonial movement, founder of PAIGC in 1956, and MPLA together with Agostino Neto.

The independence party took the leadership of the movement for the emancipation of the country and carried out a peaceful campaign to bring the anti-colonial cause among the population and weave a network of international support by establishing relationships with friendly countries.

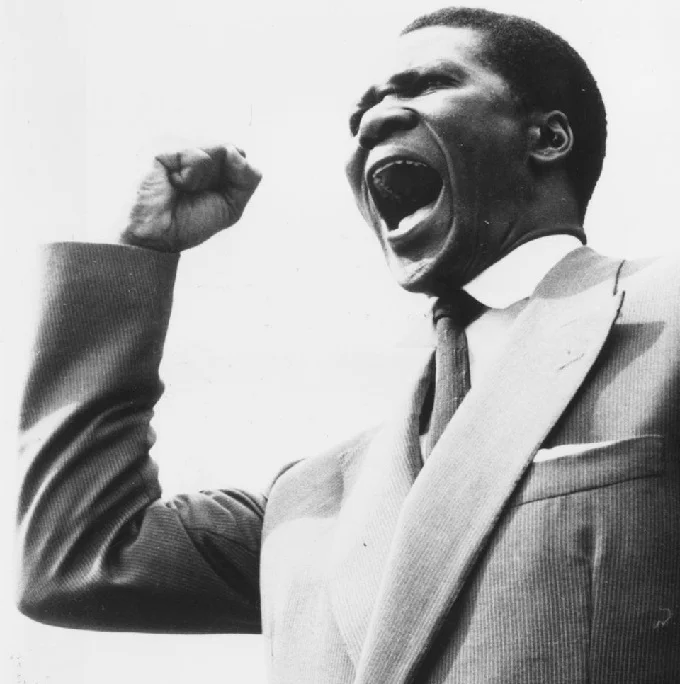

Also, thanks to the diplomatic skills of Amilcar Cabral, both objectives were achieved, and the PAIGC found good allies in both Sékou Touré, president of neighboring Guinea, and Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana and political leader of the Pan-Africanist movement.

In the meantime, the Lisbon regime had refused to open negotiations with the PAIGC, partly because it was adamant in its decision not to leave the overseas territories and partly because it did not fear the independents militarily. In addition to the closure of the negotiation channels, it was the so-called “Pidjiguiti massacre” of August 1959, in which the Portuguese police shot at a dockers’ strike, killing 25 people.

At that point, the party of Amilcar Cabral decided to go underground and adopt the armed struggle as a strategy to obtain independence, starting a war that bloodied the country for 11 years. The PAICG moved its headquarters to Conakry, in neighboring Guinea, and set up training camps and shelters in Senegal and Ghana.

However, Cabral’s forces were always clearly outnumbered by the Portuguese, so rather than face them directly, they devoted themselves to sabotage, attacks against barracks, and territorial control in rural areas.

At the beginning of 1970, the PAIGC controlled almost two-thirds of the territory, but it was beginning to yield militarily, partly because Portugal had greatly intensified its offensive. An operation that would have deprived the independentists of their leadership and the support of Touré’s Guinea seemed a strategic choice: in this climate, the decision to deploy Operation Mare Verde matured.

Lisbon was paying a high price for the war. Years of conflict had isolated the regime internationally, alienated the consensus of the population and the military, and impoverished the country. The proposal of decisive action for the conflict in Guinea-Bissau, therefore, interested the army even if it included invasion and interference with a sovereign country like Guinea.

Operation Mare Verde

In the night between November 21 and 22 began Operation Green Sea, with the infiltration by the sea of the Portuguese contingent. The group was led by officers from Lisbon and composed of at least 400 Portuguese naval riflemen, Afro-Portuguese soldiers, and Guinean opponents. The group landed in the vicinity of Conakry with the intent of overthrowing Sékou Touré, kidnapping Amilcar Cabral, sabotaging the PAIGC infrastructure, and freeing some Portuguese prisoners. Objectives that, if achieved, could have reversed the fate of the conflict overnight.

The first target of the invaders was the headquarters of the PAIGC and five ships used by the rebels for supplies, which were destroyed. In quick succession, some strategic targets were also attacked, such as the power station and a radio tower of the city, as well as the prison of Camp Boiro where some Portuguese soldiers captured by the independentists were detained.

At that point, the group split up, and one part dedicated itself to the destruction of the PAICG facilities and the kidnapping of Amilcar Cabral, which, however, failed immediately. The resistance of the militants and of the Guinean police could not do anything against the attackers, the action was foiled by the fact that the independence leader was not on the spot but on a diplomatic mission. This group then quickly withdrew by sea.

The remaining contingent, now reduced to less than 200 people, tried to make the population of Conakry rise up against the government, convinced to be able to gather consensus among the population of the capital. However, this did not happen, also because the infiltrators were not able to transmit their messages to the population from the radio station they had occupied, nor to capture important officials of the Guinean defense. After being repelled from the presidential palace, they were forced to follow their comrades in retreat, but at least sixty were captured, including six Portuguese officers. Operation Green Sea had failed.

Responses and Implications

The first and most immediate implications of the failed coup d’état was an internal purge of the Touré regime, which hit hard at the top ranks of the government and the army. Many opponents were ousted, and there were several death sentences and an unknown number of extra-judicial executions. The purges went on until 1973, also affecting members of the executive and ministries.

The international community also reacted, accusing Portugal of having invaded a sovereign state by military means and of having violated Guinea’s right to self-determination. The condemnation was sanctioned by Resolution 290 of the UN Security Council on December 8, 1970, and by a unanimous motion of the Organization for African Unity (OAU).

There were also important manifestations of solidarity with Guinea and the PAIGC on the part of countries such as Cuba and the Soviet Union, but also others such as Nigeria and Algeria. With this renewed support also came substantial aid and armaments for the PAICG with the aim of discouraging a new Portuguese invasion, rebalancing the military advantage obtained by Lisbon in recent years.

From the beginning of the seventies, also due to the negative impact of the failed operation Mare Verde, the colonial war and the fascist regime of the Estado Novo progressively lost the population’s support, especially that of the military.

The discontent resulted in the Carnation Revolution of April 25, 1974, which deposed Marcelo Caetano and re-established the democratic order. The first government elected in 1975 immediately proceeded to complete decolonization, which in reality was already almost complete in Guinea-Bissau.

With Portugal increasingly weak and isolated, in fact, by 1963, only the capital Bissau and a few other cities remained in the hands of the colonists, while the territory was de facto administered by the PAICG. The sore point of the matter remains that Amilcar Cabral could not attend either of the two phases of independence for which he had fought.

After having escaped from Operation Mare Verde, he was assassinated in 1972 by an official of his party in circumstances never clarified, so the first president of Guinea-Bissau was his brother Luís.